629 Pakistani Women Sold as Bride‑Slaves to Chinese Men Since 2018

Despite documented proof and arrests, Pakistan’s efforts to break up trafficking networks have stalled due to its financial dependence on China.

Pakistani investigators have compiled a list of 629 Pakistani girls and women trafficked as bride-slaves to Chinese men roughly between January 2018 and April 2019, along with the names of their husband-enslavers, and the dates of their forced marriages, according to an investigation by the Associated Press. More women are believed to have been enslaved since.

Despite this documentation and the arrest of 31 Chinese nationals charged with trafficking, Pakistan’s efforts to end the slave-trade network behind these human sales have stalled due to the country’s financial dependence on China; all 31 alleged traffickers were acquitted by Pakistani courts in October.

Activists and officials with knowledge of the country’s trafficking investigation speak of an intimidation campaign by the government toward those attempting to curb trafficking and bring about justice for the women enslaved, citing pressure from above, abrupt transfers of civil servants and investigators, and an unofficial moratorium on media reporting related to the issue.

“No one is doing anything to help these girls,” one of the officials told the AP. “The whole racket is continuing, and it is growing. Why? Because they know they can get away with it. The authorities won’t follow through, everyone is being pressured to not investigate. Trafficking is increasing now.”

“Where is our humanity?” he added.

Related on The Swaddle:

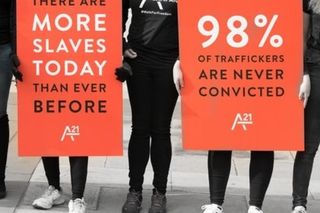

New Research Spotlights India’s Dismal Conviction Rates for Slavery‑Related Offenses

A related AP investigation earlier this year focused on Pakistan’s Christian minority, one of the poorest communities in the country, which has become a target of traffickers. Families sell daughters, some still legally children, to Chinese husband-enslavers.

“The Chinese and Pakistani brokers make between PKRs. 4 million and 10 million (US$25,000 and US$65,000) from the groom, but only about PKRs. 200,000 rupees (US$1,500), is given to the family,” an official told the AP.

Upon joining their new family-enslavers in China, many of these women are “isolated and abused and forced into prostitution,” the AP reports.

The slave trade between Pakistan and China is driven by a significant gender imbalance among the Chinese population, a result of the combined force of China’s three-decade-long one-child policy and a strong cultural preference for sons. According to Human Rights Watch, China now has 30 to 40 million more men than women.

Pakistan is not the only country from which bride-slaves are trafficked to China’s extra men. Women and girls from Northern Myanmar, Cambodia, North Korea, Laos, Nepal, Vietnam and more are caught up in a slave trade that flourishes in equal part due to impoverished circumstances, especially of minority populations, in these source countries.

China’s response to the issue varies; in June, Chinese police reportedly rescued more than 1,000 Southeast Asian women enslaved as brides as well as arrested more than 1,000 suspected traffickers and brokers. But steps beyond that appear to focus largely on image crisis management. Despite its initial cooperation with Pakistan and other countries to rescue enslaved women, arrest suspected traffickers, and despite issuing statements that pay lip service to consensual marriage, reports like the AP’s make clear China is exerting behind-the-scenes pressure to polish its image; at stake for Pakistan, for instance, is a US$75 billion aid package for infrastructure development, the AP reports.

Also behind the scenes, China appears to be outright denying enslavement is an issue at all. According to Human Rights Watch, a Chinese-government publication in Myanmar describes the “happy and pleasant road” a Myanmar bride in China will experience. Another incidence involved an activist from Myanmar who participated in a women’s rights study tour of China. They recalled one Chinese professor explaining trafficking wasn’t the problem; the problem, the professor said, was “Myanmar women don’t know Chinese culture. Once they learn Chinese language and culture, their marriages are fine.”

“Tell your government the Chinese government is doing very good things for Myanmar women,” the professor told the women’s rights activists from Myanmar, according to Human Rights Watch.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

What It Will Take to End Gang Rapes in India