A Brief History of Indian Women Protesting Gender Inequality

Indian feminists have always had your back.

Long before #MeToo, and decades before the Indian government made any laws to protect women against violence, Indian feminists had been fighting for the right of women to exist unscathed in public and private spaces.

The Indian women’s movement began in 1975, working toward intersectionality and catapulting gender violence into national discourse. While a barebones women’s movement was being carried out in India since the 1920s, it only served as a complement to the political revolution taking India by storm.

In 1920, even Mahatma Gandhi, who touted himself as a champion of women’s rights, urged “women to stop fighting for voting rights and concentrate their efforts instead on ‘helping their men against the common foe,’” according to “Domestic Violence and the Indian Women’s Movement: A Short History.”

Once the country gained independence, Indian leaders discouraged female revolutionaries from mobilizing, instilling a ‘ghar/bahir’ divide and reinforcing strict gender roles for women as the protectors of the home.

The feminism between Indian independence and the late 1970s was not an intersectional phenomenon; upper-caste women alone took up political and social causes after being advantaged by the nationalist movement that emphasized the education of Indian women. Even this resulted more by accident, as the movement was aimed more at getting a leg up on Western women, in terms of education, than it was at challenging ‘Indian’ gender roles, per “Indian Women and Protest : An Historical Overview And Modern Day Evaluation.” The vast majority of women at this time were still imprisoned in “a ‘nonactivist and nontransformative’ state, whose superiority over all others meant she now embodied ghar and the ‘unchanged domesticity in an age of flux’.”

It was only in the late 1970s that women began mobilizing around issues of gender violence, such as “rape, dowry deaths, wife-beating, sati (the immolation of widows on their husband’s funeral pyre), female-neglect resulting in differential mortality rates, and, more recently, female feticide following amniocentesis,” according to “Organising Against Violence: Strategies of the Indian Women’s Movement.”

One of the first major protests after this newfound, nationwide consciousness kicked in among female revolutionaries occurred after a high court overturned the convictions of two police officers in the Mathura rape case, wherein a 9-year-old girl was raped inside a police station.

In the next decade, the movement witnessed the proliferation of thousands of NGOs, political party-affiliated women’s organisations and other grassroots efforts as a result of greater media attention toward gender violence. This, in turn, spurred more mobilization and legal reform.

For example, in 1983, Section 498A was adopted into the Indian Penal Code, which made “cruelty” toward wives a criminal offence that could be punished with up to five years in jail. The law, which soon fell flat when cases under its purview were put under the jurisdiction of family courts to resolve marital disputes instead of punishing perpetrators, was still the first major legal victory since women started mobilizing at a large scale for change.

Over the course of the next 19 years, six conferences were held, the purpose of which was “to come together, to share experiences, to analyse issues, to build alliances and strategies for change and to strengthen the movements,” according to “Conferences of Women’s Movement: History and Perspective.”

But these attempts at unity were also fraught with deep schisms over class and religion. The divisions framed the planning stages of the third conference in Bihar, Patna, in 1988, also called the Nari Mukti Sangharsh Sammelan. For the first time, rural groups were also included in discussions surrounding mobilization and change. At a rally attended by more than 8,000 after the conference, activists advocated for intersectionality in the women’s movement, urging urban women to link up with rural women, and urging middle- and upper-class women to ‘de-class’ themselves and take up in arms with their less privileged counterparts.

Historically, Indian women might have engaged in meek protests, such as excessive salting of meals, badmouthing their husbands behind their back, and singing songs replete with complaints, according to Appropriating Gender: Women’s Activism and Politicized Religion in South Asia. While these protests might not seem like much, Indian women were not the complacent, resigned group often depicted so in the West, the authors write. During the turn of the 21st century, furthermore, with decades of reform under its belt, the women’s movement became comfortable with taking to the streets.

And so it has. From rallying to urge the government to recognize the term ‘domestic violence’ in the early 2000s, to facilitating anti-rape laws after the 2012 Nirbhaya case, a fearless, mobilized women’s movement has been trying to effect change in an intensely patriarchal Indian society.

Most recently, 5,000 activists and sexual assault survivors completed a 10,000-kilometer-long dignity march through 200 districts and 24 states and union territories, to raise awareness about rape. While sexual harassment, assault and gender violence are still grave threats to women in India, a quote given to India Times by a survivor and activist, Bhanwari Devi, perfectly embodies the attitudes of Indian feminists from decades past:

“I will not be silenced. I will continue to fight till my last breath until I get justice.”

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

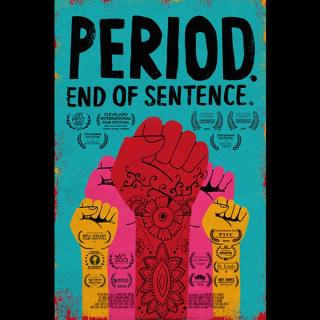

Period Documentary Oscar Proves How Far We’ve Come in Talking About Menstruation