A Crash Course on the Male Reproductive System For Anyone Who Needs It

It’s never too late to learn.

After a recent conversation with a male friend in his 30s about vasectomies and a male contraceptive injection that is in the works, I found he didn’t quite know the difference between sperm and semen. He thought if he got the injection, which blocks sperm exiting the body for up to 13 years — he wouldn’t be able to ejaculate for that long.

Which brings me to my next point: most of us don’t understand our reproductive anatomy. In India, sex education is only for the privileged, and even then it’s a sham. Embarrassed, untrained teachers usually skip over the chapters about the human reproductive system when staring at a classroom filled with teenagers, even in the best schools. When they don’t, it’s barely touch-and-go. So, if you have somehow made it to your 20s, 30s, or above, and don’t quite know the details of how the male reproductive system works outside of the ‘erection-sex-orgasm cycle,’ this primer is for you.

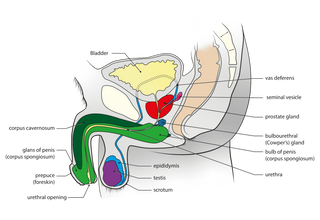

A diagram of the male reproductive system (Image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

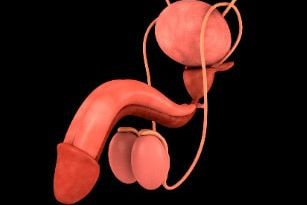

The male reproductive system can be largely broken into four primary sections: the testes, the duct system, a system of accessory glands, and the penis — and the first three sections do about 99% of the task of producing and transporting semen in and out of the fourth section.

Related on The Swaddle:

An Anatomical Guide to Female Genitalia for Anyone Who Needs It

The male primary reproductive organs are the two testicles, or testes, colloquially known as ‘balls’ for their resemblance to, well, small balls. They are responsible for making sperm and testosterone, the male sex hormone. They begin developing inside the abdominal cavity (near the kidneys) when a male child is in the womb, but two months before birth or shortly after, they ‘drop’ into the scrotum — a pouch that dangles outside the abdomen, below the penis.

Even though this might seem like an especially vulnerable location for what is essentially the most important part of the male reproductive system, there is a method to the madness. Sperms are highly sensitive to temperature; their production, mobility, and effectiveness start decreasing at core body temperature (37 degrees Celsius). So, the balls are located outside the body, in a scrotum divided into two sacs, to achieve a lower temperature to be able to carry out sperm production.

Each testis is filled with tubules, which are basically sperm factories. This sperm-making work is catalyzed by a host of helpful cells around and inside the tubules such as the Sertoli cells (also known as “nurse” cells), which nourish the sperm, and the Leydig cells, which secrete testosterone.

When puberty strikes, the brain signals these cells into activation — they, in turn, create large concentrations of testosterone bound with protein and trigger the sperm-making process. Once sperm is created inside the ‘balls’ through a process of repeated cell division, it takes about five weeks to grow a tail, which is how they are able to come out through the penis when a male ejaculates.

Once the sperm is ready with a tail, surrounding cells rhythmically contract to move the sperm (and a bit of fluid secreted by the nurse cells) through the tubules until they leave the balls and enter the duct system behind it.

At this point, sperm is still immobile. This is where the first stop in the duct system comes into play — the epididymis. It’s mostly made of a giant coiled duct, which has little protrusions (that increase its surface area) to help reabsorb extra fluid from the passing sperm and nourish it. This is where sperm gains energy and becomes ready to swim out at a moment’s notice when a male orgasms.

When this time comes — for ejaculation — the now fertile sperm enter the vas deferens — the tube that is ‘tied’ during vasectomies to prevent sperm from leaving the man’s body, and hence pregnancies. The tube goes up from behind the bladder and joins a system of ducts, which is where semen is made — a mixture of the sperm that has traveled to this point, along with testicular fluid and secretions from these ducts. Semen not only carries the fertile sperm, but it also nourishes, protects and finally activates its mobility for it to be able to ‘swim’ out. In fact, sperm make up only 2-5% of the total semen value, per ejaculation.

Sperm then passes through the prostate gland and empty into the urethra, which runs from the bladder, through the penis, to outside the body.

Related on The Swaddle:

A Field Guide to Having Sex while Pregnant

(At the point of ejaculation, a muscle at the neck of the bladder also tightens to prevent the urine stored in it from mixing with the semen passing through the urethra — which answers the question of whether males can pee and ejaculate at the same time. No, they can’t.)

And finally, we come to the most insignificant part of the male reproductive system, function-wise — the penis. It consists of a shaft that ends in an enlarged tip called the glans penis, which is surrounded by a fleshy layer of foreskin. There is an opening in the center from which the urethra empties out, carrying the semen or urine, as required.

The penis is entirely made up of tissues with tiny spaces within them, that gets filled with blood during sexual arousal and enlargens and hardens the penis, which is what helps it to penetrate a female’s vagina during sex so that sperm exiting the male’s body can be delivered as close to the female’s uterus as possible for a pregnancy to occur, or as in most cases, straight into a condom.

*

TL;DR: Sperm and semen are not the same things; males can not urinate while orgasming, and the penis is nothing more than a glorified delivery system that is designed to get sperm as close as possible to an egg inside a female’s uterus. You’re welcome.

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

Despite Increasing Incidence of Non‑Communicable Diseases, Countries Are Not Doing Enough to Curb Them