A PCOS Researcher Discusses Her Latest Findings

PCOS may start in the prepubescent brain, and other insights.

Polycystic ovary syndrome can be a mystifying condition for many women — in part because science itself knows so little about its causes. We sat down with Rebecca Campbell, an associate professor with the Centre for Neuroendocrinology and Department of Physiology at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Campbell, a researcher on the cutting edge of PCOS insight, told us about her most recent findings, and what they could mean for PCOS treatment. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

THE SWADDLE: What is your latest research in the field of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)?

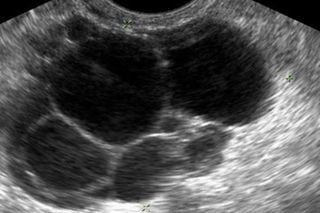

Rebecca Campbell: We are doing work in a pre-clinical model of PCOS, using rodent models that allow us to take advantage of different neuroscience tools so we can look at specific circuits in the brain. This model is reflective of a lean PCOS phenotype. PCOS tends to either exhibit phenotype that’s dissociated with metabolic syndrome so obesity, insulin those types of things. That’s currently thought to be about half of the PCOS women that are diagnosed. The other half of women that are being diagnosed with PCOS don’t tend to have a metabolic phenotype. So we refer to them as the lean PCOS phenotype. But interestingly this group appears to have more severe infertility issues. Our model exhibits a lot of the same characteristics. It has high androgen levels, so high testosterone. The ovaries look like a polycystic ovary and they are essentially infertile. So what we’ve been interested in looking at is how the brain might be involved in regulating the things that are happening in the ovary.

But essentially, what we found is that the circuits in the brain that are controlling the secretion of gonadotropins from the pituitary gland — which regulate what’s happening in the ovary — the circuitry that controls that is wired differently in the animals that exhibit PCOS. We identified some specific circuits that look really different in this PCOS model. And so what we’ve been working on now is trying to identify when those changes in the brain occur in development, and whether or not we can actually modify them with drug treatments once the condition has been established in adulthood. We found that the circuits are actually disrupted really early in development, so prior to the disease onset which occurs with puberty. Prior to any of the signs of PCOS being exhibited, these changes in the brain are already evident. So what it’s suggesting to us is that these brain changes are actually driving the disease onset.

We don’t really know what causes PCOS; there are lots of theories and lots of ideas about what might initiate it, and our particular theory, [that] we have some good evidence of is that it’s actually being initiated by these pathologies in the brain. But what we are really excited about now is that if we allow these animals to develop normally and they develop the PCOS phenotype with pubertal onset. We found that if we administer an androgen-receptor antagonist for a long period of time and we then look at the reproductive cycles of these animals, and we look at their ovaries and we look at their brains, what we found is that this long term blockade of androgen signaling is able to reverse the wiring changes in the brain back to a brain that looks normal. And this is associated with a restoration of reproductive cycles, and ovaries look much healthier and exhibit signs of ovulation. So it looks like even though this disease appears to be kind of programmed early in development, it can be reversed in adulthood. So this is pretty exciting for us and we want to now look into the mechanisms of how blocking androgen is able to restore the health from the disease, and then also determine whether there are critical windows in blocking androgens to be able to restore normal fertility, and to ultimately be able to restore it long term. So what we really want to know is can we block androgens, restore normal brain wiring, restore normal ovarian function, and then take the drug away and maintain that healthy state long term. So essentially curing the disorder. But these are things we are yet to answer.

THE SWADDLE: To speculate, would this new treatment only be possible or applied to the lean phenotype or would it also potential apply the other phenotype?

RC: So we don’t really know yet. But that’s something that we’re hoping to look at as well. We would like to see if androgen blockade can do some of the same things. But what I think we will find going forward in looking at PCOS syndrome is that there are probably a number of sub-phenotypes that develop from different origins and they’re probably going to respond differently to different drug treatments. So we might be looking at something that is specific to this particular prenatal androgen associated lean PCOS phenotype. But we’re definitely going to look and see if we can get with the obese phenotype.

Right now [the different types of PCOS] are all kind of lumped together into just one syndrome. I think it’s changing clinically; people are now referring to 4 separate phenotypes. But I think we’ve got a long way to go to understanding what’s characteristic to each of those phenotypes, so that we can treat them accordingly.

THE SWADDLE: A lot of women get diagnosed with PCOS, but there’s no sufficient information about what’s actually going on with their bodies. Is this just a communication gap between the patient and the healthcare provider, or is this actually a knowledge gap in science?

RC: I think it’s a global issue with patients feeling like they don’t know what’s happening in their bodies. And getting really poor information. And that’s partly due to the fact that we just don’t know. But I also think so many women with PCOS are so desperate that there’s so many ‘miracle cures’ on the internet and all kinds of junk that women just get swayed with. So I think it is a knowledge gap and I think we need more basic science. But we also need better communication between the basic scientists and the clinicians, which I think is beginning to happen, but yeah, I think we got a long way to go.

THE SWADDLE: Your research is its early stages, but how close or how far are you from any of this [mouse research] being applicable to humans?

RC: Yeah, thank you for asking that, because I definitely don’t want spin and I don’t want people to go and treat themselves with something that’s not safe. So, one of the issues is that this drug is used already to treat symptoms of PCOS that are associated with hyper-androgenism. The problem with these anti-androgens that are available is they’re all off label. So they’re drugs that have been developed for men, typically for things like prostate cancer, they’re not designed for women, so they can have toxicity issues for long term use. We need better anti-androgen drugs in women, so we’re talking to some pharmacologists about doing some drugs development and looking at what we can achieve in our model, see if we can find better drugs, so that’s one issue. We need better anti-androgens. The other issue is that currently this type of anti-androgen therapy in women with PCOS is always prescribed with a contraceptive pill, and that’s because you wouldn’t want to become pregnant and carry a male offspring while you were on an anti-androgen. Basically it can cause birth defects; it can cause problems in development of male external genitalia. So it’s contraindicated with pregnancy. So we need to figure out, can we identify the critical windows of treatment, treat women with an anti-androgen that’s developed for women, then take them off the drug so that they have a window of time that is appropriate for conception and carrying a baby in a safe way where this drug is no longer in their system?

So these are some of the hurdles that we have to get over before this would actually reach the clinic. But what we are doing in addition to our pre-clinical work is we’re working with a group in Sweden that have access to amazing clinical health registries. And we’re looking at whether there are links between women with PCOS that have been on anti-androgen therapy and their successful live birth outcomes. So we’re looking at whether there is any evidence kind of retrospectively in women that have been on anti-androgen therapy, that have had easier time conceiving naturally. So if we can find evidence for that then it suggests that there may be a critical window type of issue, where we can get beyond drug treatment and the women remain fertile. These are some of the things that we are up against. So I wouldn’t want to put any particular time frame on when this might actually be in the clinic, but it gives us the first clue really that there’s something that we can do that might reverse the phenotype.

THE SWADDLE: It’s almost like a full system syndrome you’re talking about. Does this challenge what we think of as normal, what it means to be a normal woman, or normal reproductive capabilities?

RC: We are just beginning to really understand the tip of the iceberg [regarding] what is programmed early in development. So many of the small influences that occur during prenatal development are programmed in our DNA or in our brain wiring. And ultimately, we exhibit it much much later it in life, and so there’s this whole concept of prenatal programming, this prenatal prescription of how to actually develop a healthy baby and we really don’t understand all the different things that can contribute to either good health or pathology later on. We are really just beginning to understand that, but I think it’s becoming really clear that there are a number of things that can impact reproductive female health in particular later in life. But it’s a spectrum, so there’s going to be a healthy level of androgen exposure that’s not going to have any impact in one woman, but in another woman who has a genetic predispositions or some polymorphisms may actually be susceptible to that same level. We still need to figure out what are the contributors to things like elevated androgens in-utero. We know some of them but we don’t really understand how much they contribute. And then what are things that actually make women predisposed to be impacted by those high levels of androgens.

As told to Liesl Goecker.

Related

Vaginal Swabbing During C‑Sections May Not Be Transferring Healthy Microbiome to Babies