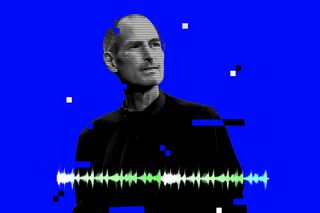

A Podcast With AI‑Generated Steve Jobs Raises Ethical Concerns

Whose likenesses do we get to use after their incapacitation — and can they consent?

This week, famed podcaster Joe Rogan interviewed Steve Jobs. The catch? It was an artificial intelligence version of Steve Jobs. Podcast.ai, the platform that hosted the episode, featured Jobs’ likeness as its first experiment with talking to dead people, due to “his impact on the technology world and how he continues to inspire people, much after his death too,” according to Interesting Engineering.

Many fans of the late prodigious tech guru received the initiative with gratitude. But there’s a fundamental issue missing from the conversation: Steve Jobs didn’t, and cannot, consent to this. Any AI likeness of him, then, speaks for him and in his name, all without his sign-off.

It’s an ethical minefield that AI ethicists are just beginning to navigate. At the heart of the debate is that the resurrected person is meant to serve the needs of others — thereby compromising the privacy and agency of the person who once lived. “… where do we draw the line between life and death, or between remembering someone and recreating someone?” asked Edina Harbinja, a senior lecturer in media and privacy law at Birmingham’s Aston University.

When their data is fed to AI to impersonate, it not only undermines the depth of the person, but also their ownership of their own personhood. Steve Jobs may have been a public figure, but he still belongs to Steve Jobs — the kind of “digital immortality” that allows others to bring a version of him back to life, then, is ephemeral. “It’s like next-level identity theft,” noted The Washington Post, about big tech companies patenting softwares that can bring dead people back to life via AI.

Some technologies are allowing people who are still alive to create their digital counterparts that will live forever. “When a user decides to keep his counterpart active for eternity, he will have the extension of himself alive forever… Some years from now, your great-grandchildren will be able to talk with you even if they didn’t have the chance to know you in person,” developer Henrique Jorge, told Reuters.

Related on The Swaddle:

LinkedIn Has Over 1,000 AI‑Generated Deepfake Profiles, Find Researchers

This highlights how it’s one thing to archive someone’s data after they’re gone — and quite another to use the data to recreate them digitally. Take the famous case of the grieving Canadian novelist who, unable to bear living without his dead fiancée, decided to feed her chats and background information to an AI software that then created a chatbot designed to sound like her. The program was later shut down after concerns about misinformation — and importantly, concerns about chatbots being fine-tuned to be overtly sexual or even racist. That’s not to say that the novelist did this — but that anyone can, with any dead person’s data.

Amber Davidsson, a researcher who studies pornographic deepfakes, worries about the implications of making the digitally resurrected dead do things they would not have done in life. “Add into that the layer of that person being gone… they don’t get to respond,” she told Wired.

It ushers in a scary possibility — “that we might come to not care very much whether grandma is human or deepfake,” according to Eric Schwitzgebel, a professor of philosophy. That’s almost the case with the woman who recreated her best friend using AI after he died in a car crash. “We are still in the process of meeting Roman,” said a friend of Roman’s. The problem is arguably compounded when it comes tocelebrities who have passed on — as the infamous documentary about Anthony Bourdain’s life showed. It used Bourdain’s own voice to speak out loud things he never said — only wrote down — in his life: “My life is sort of shit now. You are successful, and I am successful, and I’m wondering: Are you happy?”

The big ethical questions around AI recreations of people are their potential use for misinformation: what if we got dead politicians and statesmen, whose images are integral to the history of a place, say or do things that were antithetical to their values? With celebrities who have relatively less control over their personas, this could be even trickier. Last week, the actor Bruce Willis fielded rumors that he had sold his likeness to a deepfake company to continue acting for him after he was unable to. He clarified that he didn’t — but he may lose the right to his own voice anyway. It’s particularly murky, considering Willis’ struggle with illness that impairs his speech.

Regardless of whether the podcast with AI Steve Jobs is illuminating, if AI-generated likenesses are readily deployed to not only speak for but actually be the person they’re impersonating, it spells trouble for society as a whole. For one, we may be unable to respect the consent and agency of people over their own personhood. For another — we may not care if a likeness comes to stand in for a real person, robbing them of the essence of what made them unique and irreplaceable in the first place.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

The Human Genome Contains ‘Dark Matter.’ What Is Its Purpose?