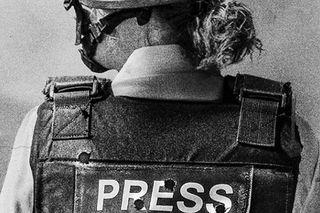

‘A Private War’ Reflects the Everyday Trauma of Journalists in the Field

As the definition of ‘frontline’ blurs, reporters’ physical safety and mental health pays the price.

A long stretch of concrete buildings shred to rubble, under a cloud of dust, up to the horizon. Doors shutting loud. Wails of women. Gunfire. Crumbling corpses.

A Private War opens with a montage of these disturbing scenes, setting the tone for the audience to bear witness the life and work of acclaimed British war correspondent Marie Colvin, who was killed – along with French photojournalist Remi Ochlik – while covering the siege of Homs in Syria, in 2012. The recently-released movie, which has earned actor Rosamund Pike a Golden Globe nomination, takes the audience through Colvin’s workplace: the frontlines of war. At the same time, it does not shy away from revealing the price that war correspondents pay in their line of work. Several war correspondents have fallen, while many others have lasting impact on their mental health.

But the definition of frontlines has been blurring in recent years. Last year, I was beaten up by the police and detained while reporting on a slum demolition in the heart of Mumbai, not far from my home. As I sat in the police station, bruised, and clenching my fists, lest the cops notice me trembling, I was incommunicado for nearly four hours, waiting for someone to show up. Little did I know that this episode would cause me trouble breathing, each time I notice a posse of police personnel, especially in crowds. But I have not yet reported from a war zone; I was not supposed to feel this way. I did not know whom to speak to, to sift through my feelings and physical reactions, even as I went about doing my job, of telling stories, with the hope that it mattered.

And this is why A Private War hit home for me, as well as those who know too well what it means to report from the frontlines. With the frontlines blurring as to what a war zone really is, and how the public views journalists in general, the mental health of journalists is at risk: they’re not getting the help they need, and neither are they able to ask for it.

The fallout

Even though Kabul-based freelance journalist Ruchi Kumar has never been embedded with either the foreign or Afghan forces, she has reported about attacks in Kabul, which have been taking place almost every week in 2018. The Global Terrorism Index for 2018 listed Afghanistan as the deadliest nation in the world. Recent attacks in Kabul by ISIS have been among the deadliest in the world this year.

“The war has come to the Afghans’ front porch and they deal with it every day. But I am in a privileged position because I can leave whenever I want to; I live in a slightly safer location in a slightly protected neighbourhood, because I am a foreigner. That privilege itself is sometimes disturbing,” Kumar told me.

Towards ensuring the safety of journalists, and equipping them with the necessary tools to work in difficult environments, the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) began to offer comprehensive hostile environment and first-aid training (HEFAT) when it started a reporting initiative in six, conflict-prone African countries five years ago. The course is expensive and offered by several institutions other than the IWMF. But for people like Kumar, the cost is prohibitive. She was once offered a fellowship to take this course, but was rejected a visa because she has been living in Kabul – exactly the reason why she needed to be equipped with the skills offered by HEFAT.

In 1996, Amantha Perera was a college student in Colombo, listening to the scores of the cricket World Cup on the radio, which was interspersed with reports of casualties from the war in Sri Lanka. “It was a number’s game,” says the veteran journalist, who reported on the war from the late 1990s until 2009. It was only when he traveled to the frontlines, in the north and east of the country, did he notice the lives of civilians. (It was also this war in which Colvin lost an eye in a grenade attack in 2001; she wore a patch on her eye for the rest of her life.)

One of Perera’s last war despatches “Escape From Hell” was in April 2009; he had also covered the tsunami in 2004. Perera’s former editor at the Sunday Leader, Lasantha Wickrematunge, was murdered in 2008 and Perera reported on the murder and investigation. But it had a profound impact on him and he stopped working on that story. It was only in 2011, when he began to work as a fellow at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma that he became acutely aware of the trauma from covering both events.

“I realised that I had neglected a certain part of my life that was as important as being physically fit. The culture at any newspaper is that of being bullet-proof, where we behave as though nothing affects us. We create this vacuum between ourselves and the macabre we see; we dehumanise the process. Looking back at my war writing, I had left out human emotion in many of them, and that was partly a reaction to the way I was working,” Perera said.

“They are people who felt that they could confide in me, open up their homes and lives to me. They have given me the permission to tell their stories to the rest of the world.”

This holds true for journalists reporting on anything that impacts humanity at large: sexual assaults, riots, natural disasters, and others. Journalists are expected to remain stoic; the pressure on male journalists to just get the job done, from one assignment to another, is far more.

“If a journalist speaks about being affected by what s/he sees, it is presumed that it is a judgement on the person’s journalistic skills,” Perera said.

Perera began to speak about his trauma in close circles, and subsequently, at public forums. As the Asia-Pacific regional coordinator at the Dart Center, he understands that journalists are slow to open up, because it is often a clash of a person’s personal and professional lives.

The situation is also risky for freelance journalists. I was detained because I had acted on my journalistic instinct of covering a slum demolition in which the resisting residents were meted with violence. I was not commissioned by any editor to cover it. I could not therefore expect any sort of protection from any institution. In August 2017, freelance journalist Kim Wall was sexually assaulted and murdered when she had gone to interview a submarine inventor in Copenhagen – one of the safest countries in the world. Her murder reminded journalists of a grave reality: one’s gender alone can be a deciding factor of what places can or cannot be safe. Kumar’s diverse reporting from Afghanistan – and her inability to undergo to HEFAT – is testament to the precarity of freelance journalists.

The insecurity of finances is coupled with that of getting stories published.Perera acknowledges what freelancers miss out on: “Even if a freelancer is contributing to the best news organisation, there is no safety net of colleagues. An organisation might be able to conduct trauma training for its staff, but it’s unlikely that freelancers get to be a part of such trainings, leaving them very isolated.”

The compulsion

One of the pivotal moments in A Private War is a conversation between Colvin and her photographer colleague Paul Conroy, when she takes a break from the reporting, and opens her raw emotional wounds before him.

Colvin: “I hate being in a war zone. But I also feel compelled to see it for myself.”

Conroy: “Because you are addicted to it.”

Kumar is not sure about terming her line of work “addiction,” even though she has seen quite a few foreign correspondents returning to Afghanistan, perhaps because of the adrenaline rush. Every year, she contemplates leaving the country, but after four years, she continues to live in Kabul. “All risks around are just incidental or logistics that need to be managed. It is addictive, but not in a bad way. I have built relationships here, and they are more than mere subjects for stories. They are people who felt that they could confide in me, open up their homes and lives to me. They have given me the permission to tell their stories to the rest of the world. Even when I do leave, I know I will keep coming back. And I do know other journalists who have left but keep coming back, because that’s human,” she reasoned.

Nadine Hoffman, deputy director at the IWMF, also resonated with the way Colvin was depicted in the movie (as well as in the recent book In Extremis) — with her extreme compulsion to stay in dangerous situations when others have left, to not walk away from the victims of conflict. “Even more so than her courage, what I saw in the film was her compassion, especially for women and children trapped in devastating wars and violence. She died reporting exactly the kind of story she spent her entire life doing,” Hoffman said.

Hoffman admits that there are examples of inexperienced, young freelancers getting themselves into situations they shouldn’t be in. “But there are many others working in a very responsible way in war zones, who take calculated risks, and they know that they may pay a very high price for making the choice to work in dangerous places,” Hoffman said, adding that Colvin knew she could be killed doing her work and she believed the stories she told were worth the risk.

The coping

A lot has been written on moral injury — which is best understood as damage to the soul– whether it’s a result of covering wars or other traumatic situations like the refugee crisis. In her own experience working with reporters in conflict and post-conflict environments, Hoffman has realized that it’s impossible to witness really terrible things happening around oneself without absorbing some of them. “You can’t un-see what you’ve seen. And obviously it affects different people differently. Not everyone is going to get PTSD from this work. But the reality is that for many of our colleagues, covering conflict can have real, long-term mental health implications. It’s now commonly accepted that we need to be talking about this openly.”

Kumar knows this too well: she can avoid going into a dangerous Taliban-controlled area but cannot avoid her friends getting hurt or killed or lose their family members, and mourn someone week after week. “This year was extremely difficult, and it was easy for me to pull myself out by visiting home for a whole month, and break my schedule. Many of my local colleagues in [Afghanistan] are now going into therapy and that’s great, because some of them are on the frontlines all the time.”

As a freelancer, Kumar isn’t able to afford a therapist, but she relies on the community of journalists around her who identify with her sense of helplessness, even in the face of her duty as a journalist. Kumar knows several foreign journalists who break their reporting stints with a long vacation every few months. “It might seem very frivolous but now I know why they do it: it’s their coping mechanism.”

The toast to “being alive,” as shown in A Private War, is exactly the sense of heroism that journalists like Colvin – and so many others – typify, at a time when the press is vilified around the world. The belief in the power of journalists to bear witness, towards believing in their power to change things for the better, is what drives journalists to dangerous paths, often with consequences that leave an indelible mark.

Priyanka Borpujari is an award-winning journalist who has reported extensively from across India, El Salvador, Indonesia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Most recently, she walked 450-kms with two-time Pulitzer-winning journalist Paul Salopek on his 33,000-kms Out of Eden Walk, that traces the path of human migration.

Related

Study: Poor Quality Sperm a Cause of Recurrent Miscarriage