Academic Peer‑Reviews Are Heavily Influenced by ‘Status‑bias’: Study

“More than 20% of the reviewers recommended ‘accept’ when the Nobel laureate was shown as the author, but less than 2% did so when (an unknown) research associate was shown as the author (for the same paper).”

A recent study, published last October in the peer-reviewed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found a strong bias in the peer-reviewing processes for research papers published in peer-reviewed journals. The study highlighted that even in scientific and academic writing, names and statuses of contributing writers may precede the content of their research. These findings throw peer reviewing — one of the most standard processes of ascertaining the credibility of academic research — under scrutiny.

In academic writing, peer reviewing is the process of evaluating a researcher’s work and writing by others who share similar competencies. It is a form of self-regulation, carried out by researchers from the same field as the author whose work is under review. Under the guidance of German-born British philosopher Henry Oldenburg, The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, a 300 year-old scientific journal, is believed to be the first journal to have formalized peer-reviewing in its publishing process. Since then, it has remained a mainstay in the editorial process of all mainstream scientific and academic journals and has become a symbol of credibility for academic research. Apart from operating as a tool for regulation and standardization, peer-reviewing also acts as a means to strengthen “networking possibilities within research communities.”

This doesn’t, however, mean that the process has been controversy-free. In fact, in recent times, the integrity of peer-reviewing as a process has faced many criticisms, most commonly about a “status bias” in favor of already established researchers. In the most common form of peer reviewing, known as single-anonymized peer reviewing, the reviewers’ names remain hidden from the authors of the research but the authors’ names are not hidden from the reviewers. In such a situation, the identity of the author — especially if they are an established figure in the field — plays a vital role in determining the acceptance of their paper for a journal.

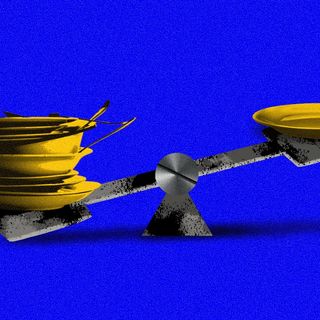

In the current study, the authors set out to find out the degree of difference between a known and unknown name’s chances of getting their research published. For their research, they carried out a field experiment wherein they sent out a review call to more than 3,300 reviewers to examine a financial research paper jointly authored by a Nobel laureate and an early career research associate. “We varied whether the prominent author’s name, the relatively unknown author’s name, or no name was revealed to reviewers,” the authors state in their study. On examining the responses of the reviewers, the researchers noted a clear sign of bias towards the Nobel laureate author. They write, “more than 20% of the reviewers recommended “accept” when the Nobel laureate was shown as the author, but less than 2% did so when the research associate was shown.” Further, “while only 23% recommended “reject” when the prominent researcher was the only author shown, 48% did so when the paper was anonymized, and 65% did when the little-known author was the only author shown.”

A previous 2014 report on Vox, for instance, observed, “prestigious authors’ papers were accepted at a rate of 87 percent when their names were present, but 68 percent when their names were redacted.”

This indicates a clear sign of a bias — whether conscious or unconscious — towards established names in the field, in the process hindering both the chances of evaluating scientific or academic work purely on the basis of their content and technical soundness, as well as those of letting younger, unfamiliar researchers a fair chance at having their research evaluated and published. Ultimately, then, this also harms the knowledge building process, as an unfamiliar researcher’s novel research faces difficulties in finding approval from reviewers. In such a setup, “reviewers could just be falling back on a cognitive shortcut that nudges them to believe a prestigious author will write a report worthy of publication.”

Related on The Swaddle:

How Google Scholar Sidelines Research in Non‑English Languages

This indicates a drastic difference in the acceptance rate, simply on the basis of the name and status of the authors, even when the work they produce is of the same quality. As Vox notes in their report on the shortcomings of single-anonymized peer reviews, this bias “could unfairly make it harder for young, untested researchers to publish their work. Or it could unfairly give leeway to an established name who has started producing shoddy work.” In a longer term, this could create unfair knowledge hierarchies, where new untested researchers would find it difficult to break into academic circles, even when their work may be as credible as that of an established name.

This points to the need for urgent reforms in the process, and perhaps even replacing it with an entirely new method of evaluation and regulation. One way in which the researchers propose in making a change could be through regularizing and mandating the double-anonymization process — where both authors and reviewers remain unaware of each others’ identities. This could easily prevent status bias as the identity and position of the author remain unknown to the reviewer. “So rather than judging a paper by the gender, ethnicity, country, or institutional status of an author — which I believe happens a lot at the moment — it should be judged by its quality independent of those things,” Timothy Duignan, now a lecturer at Griffith University, told Vox highlighting the significance of double-anonymized peer reviews. The authors of the current study also back double-anonymization as a possible alternative to current, predominantly single-anonymized, peer-reviewing processes.

Some other scientists and researchers, however, are of the opinion that double-anonymized reviews would not be the most feasible and effective method to fight status biases in the peer-review process. They instead advocate switching to open-peer reviewing models. They write, “we do not see double-anonymised review as the progressive answer to biases in peer review. We argue for sunlight instead of shadows: open peer review, with published review reports and optional open reviewer identities.” They support their statement, adding, “Such openness helps to expose human biases and to discuss them publicly. It also allows for innovations in scholarly communication models. This is essential to tackle biases at the root, instead of just trying to minimize their consequences.” The researchers in their study acknowledge their limitation in considering only single and double-anonymized peer-reviewing methods and not considering open-reviewing models for their experiment.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Philosophers Propose a New Theory to Explain Why Men Don’t Share in Housework