If there’s one thing in the world that could save coral reefs, anyone’s last guess would be sex. But this guess would be correct. According to new research, the sexual activity of one type of algae could help protect coral reefs from the trials of climate change.

Published in Scientific Reportson Wednesday, the study looked at the single-celled algae called dinoflagellates, commonly found in freshwater habitats. The dinoflagellates are called “symbionts,” for they share a symbiotic relationship with the coral ecosystem. The coral provides the algae with a protected environment and elements they need for photosynthesis. Like a responsible partner, the algae produce oxygen and bolsters the health of corals in a warming climate.

Only recently, a study showed that climate change had destroyed almost half of the global coral reefs since the 1950s. Pollution, warming waters, overfishing, and physical destruction all play a role in this deterioration. “Most stony corals cannot survive without their symbionts, and these symbionts have the potential to help corals respond to climate change,” the researchers said in a press release.

Reefs host staggering biodiversity, and any damage threatens the sustainability of a life-preserving and forming an ecosystem. A healthy coral reef further protects coastlines from storms and erosion and becomes the source of food and income for half a billion people.

The chain to keep this process going may come down to sex.

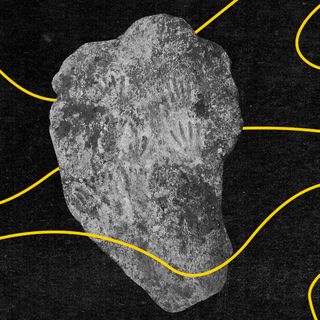

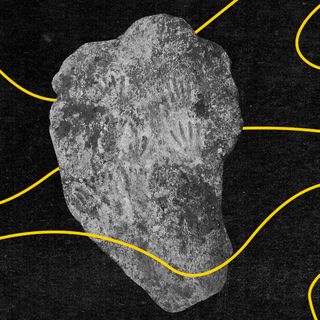

So, the more algae symbionts present, the better it is for coral reefs. Till now, scientists knew dinoflagellates multiply by mitosis; that is, they split in half and populate. The new research, however, shows the tiny creatures are also capable of reproducing by sex. This means more algae symbionts in the system and that better, more efficient strains of the symbionts will serve the coral ecosystem.

“This is the first proof that these symbionts when they’re sequestered in coral cells, reproduce sexually, and we’re excited because this opens the door to finding out what conditions might promote sex and how we can induce it,” Lauren Howe-Kerr, a researcher at Rice University and one of the authors, said.

Related on The Swaddle:

Marine Scientists In Hong Kong Are Rebuilding Coral Reefs With 3D‑Printed Tiles

A reproduced symbiont is better than the product of mitosis because the offspring of dividing algae only inherit DNA from their one-parent cell. “They are, essentially, clones that don’t generally add to the diversity of a colony. But offspring from sex get DNA from two parents, which allows for more rapid genetic adaptation,” Adrienne Correa, a marine biologist at Rice University, and one of the authors said.

The genetic variation the researchers speak of more will also make the symbionts more resilient to environmental stress. These populations that become more tolerant will be able to benefit the coral systems directly. “For coral symbionts, that means growing them under stressful conditions like high temperatures and then propagating the ones that manage to survive,” Correa said.

“So if we can get the symbionts to adapt to new environmental conditions more quickly, they might be able to help the corals survive high temperatures as well, while we all tackle climate change.”

Sex’s healing and recovery powers may not be unheard of. Research from 2004 highlighted the benefits of sex to counter environmental stress. According to the scientists, a round alga called volvox protected itself against rogue molecules through sex. In the current study, symbiont sex in the coral reefs may result in a more potent strain of dinoflagellates, which helps protect the ecosystem.

The researchers hope to investigate what triggers sexuality in symbionts and find ways that can “accelerate the assisted evolution of a key coral symbiont to combat reef degradation.”

Reef degradation is a growing environmental concern, one that impacts both marine life and humanity. “The world’s coral reefs do more for the planet than provide underwater beauty,” National Geographic noted.