“It is very hard for me to understand number arithmetic,” one Quora user noted, about their experience living with dyscalculia. “I learned that it was obvious to some people that 12 + 5 is 17 but I actually have to think and count it consciously. My mind just cannot process numbers naturally… It is surprising how much math and being smart is associated to number arithmetic.”

Dyscalculia, colloquially called “math dyslexia,” is variously considered a learning disability, a part of the neurodivergence umbrella, or a neurodevelopmental issue. It is characterized by difficulty in processing and understanding certain mathematical concepts. Some signs include trouble differentiating between magnitudes of numbers (for instance, counting backward and forwards), difficulty in understanding arithmetic (like remembering the multiplication table), or a low spatial awareness (sorting out left from right).

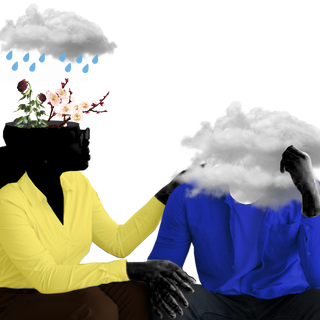

Dyscalculia manifests in someone’s everyday life in far subtler ways that go beyond classrooms. Being on time, navigating directions, negotiating finances, and other aspects of life are implicated in people with dyscalculia; but these factors often misjudged as laziness, or worse, stigmatized as “less smart.”

And, yet, the diagnosis rate for dyscalculia remains low — leading many to be unaware of what they’re living with. For many, the signs start to show as early as elementary school — but are often dismissed as simply being bad at maths. “A colleague recently noticed and said ‘are you a child?’ When I told him I have dyscalculia, he tried to laugh it off. People don’t see it as an actual disability,” Chris Long, a person with dyscalculia, told ABC.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) recognizes dyscalculia as a “specific learning disorder,” along with impairments in reading and written expression. It defines SLD as “a neurodevelopmental disorder of biological origin manifested in learning difficulties and problems in acquiring academic skills markedly below age level and manifested in the early school years, lasting for at least 6 months, not attributed to intellectual disabilities, developmental disorders, or neurological or motor disorders.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Why People Living With ADHD Are Often Misjudged As ‘Lazy’

Dyscalculia is commonly held to be a result of the brain developing differently, while some research also points to genetic causes.

There is no known “cure” for dyscalculia as such — and interventions often attempt to fill in the learning gaps in individuals with dyscalculia. Some countries recognize dyscalculia as a disability requiring support; students with a dyscalculia diagnosis may, in some instances, be allowed provisions that accommodate their learning needs in the classroom, such as being allowed a calculator, extra time, tutoring to target core skills, putting up posters to reiterate fundamentals, and others.

Moreover, dyscalculia also co-occurs with dyslexia and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD, but researchers are yet to establish the link between them all. Experts also note that research around dyscalculia is still in its infancy — and there is debate as to whether there may actually be many different types of dyscalculia according to the symptoms. This also means that it is difficult to establish its prevalence: “These uncertainties concerning which behavioural phenomena should be considered central to DD naturally make it difficult to establish prevalence rates,” notes one study.

Similar to dyslexia, however, a common misconception about dyscalculia is that it is a children’s learning disability. Its prevalence in adults, however, can often affect their lives in the workplace or other social dynamics, as many advocacy groups have pointed out.

This is where seeking a diagnosis helps. As with any kind of neurodiversity, receiving a diagnosis for dyscalculia helps people organize their lives and advocate for themselves better. “The condition is something they were born with, and is beyond their control, like the color of their eyes or the shape of their fingers. It helps to know that,” Ronit Bird, a dyscalculia specialist told Additude Mag.