Ambedkar Didn’t Endorse a Time Limit for Caste‑Based Reservations. Why Did a Supreme Court Judge Claim He Did?

The idea shapes the narrative that caste-based reservations are holding back development more than caste-based discrimination itself.

The Supreme Court on Monday delivered its long-awaited verdict on the constitutional validity of reservation schemes for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS). A five-judge bench presided over the matter, with three of the judges upholding the constitutionality of the 103rd Constitutional Amendment that reserves 10% seats in education and public service for individuals hailing from families with an annual income of less than ₹8,00,000. Notably, only those individuals who are not covered under any other existing reservation scheme are eligible for reservations under the EWS Quota — effectively making it a quota exclusive to the upper-castes.

One of the judges in the bench, Justice J B Pardiwala, while upholding the validity of the EWS Quota, erroneously claimed that Dr. B. R. Ambedkar — the chairman of the drafting committee of the constitution, as well as among the fiercest champions of social justice provisions — wanted caste-based reservations to continue only for 10 years. “The idea of Baba Saheb Ambedkar was to bring social harmony by introducing reservation for only 10 years. However, it has continued for the past 7 decades,” The Print quoted Justice Pardiwala as remarking. Justice Pardiwala was repeating in court a popular, oft-heard argument against caste-based reservations. In reality however, this idea is rooted in misconception. Endorsing this argument in court is a dangerous position to propagate, and may have severe consequences for the future of social justice and affirmative action as they are perceived in India.

A closer inspection of details and documents on the history of reservations offers a different story. Anurag Bhaskar, assistant professor of law at the Jindal Global University, debunks in detail the myth of Dr. Ambedkar insisting on a time-limit for reservations. Analyzing historical material available from the time of the Poona Pact to the Constituent Assembly Debates, Bhaskar points out that Dr. Ambedkar never argued for a time limit for caste-based reservations.

During the Poona Pact, Dr. Ambedkar, Gandhi, and others were discussing a time-limit for implementing political reservation for the Depressed Classes, following which Dalits would be offered a referendum to decide whether they were satisfied with the existing provisions for their political reservations. The discussions never concerned total discontinuation; moreover, the idea of the referendum was eventually dropped.

Similarly, during the Constituent Assembly Debates, the proposition for a ten-year period for caste-based reservations was actually arrived at as a compromise to bridge conflicting views. In fact, it was Dr. Ambedkar who, dissatisfied with the ten-year clause, suggested making use of constitutional amendments to keep extending these provisions.

It is important to note here that the entire discussion on time-limits to caste-based reservations pertained only to political caste-based reservations — not to education and public service. Public officials endorsing the ten-year limit in the name of Dr. Ambedkar is, then, a distortion.

Related on The Swaddle:

All the Arguments You Need: to Advocate for Caste‑Based Reservations

Dr. Ambedkar is possibly the most revered figure across all lower-caste communities. His writings, principles, and politics, remain a guiding principle for all anti-caste and social justice activists and political groups in the country. As such, pushing the concept of a 10 year limit by attributing it to Dr. Ambedkar arguably delegitimizes these groups and activists and publicly question their own dedication to his quest for social justice.

The idea that Dr. Ambedkar wanted reservations to continue for only ten years implicitly suggests that he believed that only ten years of affirmative action policies would suffice to undo the thousands of years of discrimination that people from marginalized castes and tribes faced at the hands of the upper-castes. This dilutes not only the constitutional protection that caste-based reservations are accorded as fundamental rights, but also the concept of fundamental rights itself.

Clubbing this idea on a verdict supporting reservations on supposed economic lines, further, is synonymous with upper-caste Indians’ conflation of individual inequality with group-based inequality. As Dr. Sumeet Mhaskar, professor at Jindal Global University, points out in a Twitter thread, this is symptomatic of “the privileged around the world deliberately conflate(ing) poverty with socio-economic marginalization based on caste, gender, race and ethnicity.” Justice Pardiwala’s interpretation of caste-based reservations views the opportunities in education and employment that the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes gain access to purely in terms of their economic significance. It then discounts the fact that even the highest ranking officials belonging to a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe face social discrimination in their lives.

Above all, pushing the idea of the 10-year limit places the onus of achieving castelessness in society on those who have been left the most marginalized by the institution. It attempts to guilt the marginalized castes into believing that they have enjoyed the “benefits” of affirmative action policies for far longer than they deserved to or were meant to, and that it is their insistence to not give up these provisions that is now causing inequality in society. It glosses over ground realities, where Dalits, Adivasis, and other Bahujan groups are still severely underrepresented in both academic as well as professional avenues. Further, by measuring caste development only in terms of reservation benefits without examining the many caste atrocities that still take place, this idea of a 10-year time-limit downplays and invisibilizes the role of caste in shaping social realities. It looks at reservations in isolation from the social preconditions that necessitate such policies.

Several anti-caste voices have cautioned that the EWS Quota is the first step by the upper-castes in eroding — and subsequently, ending — the concept of caste-based reservations to help the socially marginalized. It has been dubbed as “the quota to end all quotas.” As Dr. Satish Deshpande, professor in the Department of Sociology, Delhi School of Economics, writes in The Indian Express, “the Supreme Court has finally performed the antyeshti – or last rites – of reservation as an instrument for the redressal of caste discrimination.”

Pushing this view in court, then — especially while upholding a policy that offers reservations exclusively to the upper-castes — serves the purpose of shaping the narrative that caste-based reservations are holding back the development of the nation more than caste-based discrimination itself.

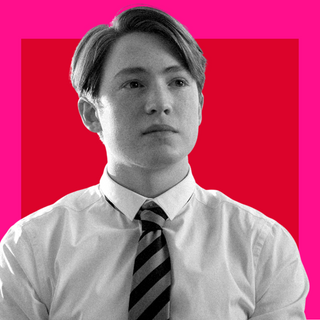

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Terrorism Definitions Exclude Gender, Neglecting Incel Extremism: Study