Angry Political Speeches Are ‘Contagious,’ Cause Voters To Mimic the Outrage: Study

“Anger is a very strong, short-term emotion that motivates people into action” with negative implications in the long term, researchers say.

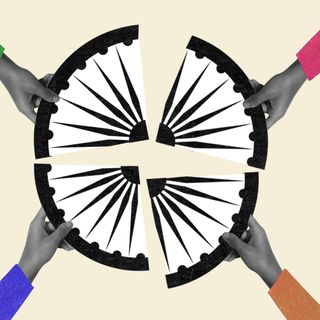

Political speech is marked with the rhetoric of anger and outrage; charged words appeal to the emotions and bias of people. New research notes how politicians making use of this strategy benefit from it more than we realize.

This is because of the impact their outrage has on the voters. Citizens may “mirror” the angry emotions of the politicians they read about or watch in the news. In other words, anger leads to more anger. The rage may fuel them to be more politically active and, chances are, they may end up voting for the angry politician.

The researchers published their findings in Political Research Quarterly this month. “Politicians want to get reelected, and anger is a powerful tool that they can use to make that happen,” Carey Stapleton, Ph.D., a researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder in the U.S. and co-author of the study, noted. He explains that anger as a strong emotion motivates people into action and is extremely contagious.

The researchers surveyed 1,400 people with different political leanings and presented them with a series of mock news stories about a recent political debate. People who read about an enraged politician from their own party were more likely to report feeling enraged than people who didn’t.

The researchers also found that angry declarations encouraged citizens to participate politically — they were more interested in election campaigns, speeches, and were likely to vote. The role of emotions in shaping election outcomes might sound intuitive, but the extent to which anger is contagious and influences behavior is notable. Previous studies have also strongly refuted the idea that voters rely only on rational, logical calculations about their political preferences.

How this anger spreads like wildfire is a fascinating process — researchers note the process of an “emotional contagion.” Experts have defined this as a process in which “an observed behavioral change in one individual leads to the reflexive production of the same behavior by other individuals in close proximity.”

This allows the anger of people in power to rub off on the voters. The voters experience the same conflict as the politician over a familiar disliked entity and echo that.

This often happens through language. In the present study, the researchers wrote a series of news stories about a debate on immigration policy. A statement such as this: “When I look at our borders, I’m enraged by what I see” was bound to stir unfavorable emotions.

Related on The Swaddle:

Google Bans Political Ads that Target Voters by Their Political Leanings

Anger also prevents people from seeking new, contradictory information. Moreover, anger makes voters feel they have more control, their political choice has consequences, and thus they are inspired to participate more.

In 2018, author Pankaj Mishra noted with resignation that we live in an “age of anger.” He adds how this anger becomes a root cause of our identities — further connecting us with the angry leader on the podium.

Notably, however, the benefit of anger in a political campaign is short-lived. “… there can be these much more negative implications in the long term. There’s always the potential that anger can turn into rage and violence,” Stapleton noted. The mob on January 6th at the U.S. Capitol is a critical example, with the outrage of a President translating into evident destruction. The post-violence election in West Bengal in India last month follows a similar pattern of bloodshed and conflict.

As India recorded more than 2,34,000 new Covid-19 infections, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s election rally in West Bengal saw a huge turnout. “I’ve never seen such huge crowds,” he tweeted. Notably, the outrage expressed by the Prime Minister and other leaders against opponents or “international conspiracies” works towards the same end in India. Other populist leaders too, such as Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and former U.S. President Donald Trump, have recorded notable electoral wins based on their angry rhetoric.

It is, in the end, a game of identifying with emotions. A study from ORF from this year explored the role emotional appeals play in persuading people to their politics. The writer cited earlier research to show the efficacy of anger. Participants were presented with two advertisements with the same policy information about a violent crime — but only one of them used anger cues. “Those exposed to the ad with anger cues showed a significantly higher interest to vote in the upcoming election,” he noted. The conclusion also noted the anger may distract voters from pressing issues.

There are two things of note in the present study. One, people who witnessed anger from politicians of their political leanings were more likely to be susceptible to this emotional contagion. In a western context, a Democrat watching an enraged speech by a Republican was less likely to be incited.

Two, and particularly interesting observation, was “The people who were the most susceptible to those shifts weren’t the die-hard partisans on either side of the aisle. They were more moderate voters.” In other words, people who were more likely to stay out of political debates tend to change their political emotions based on angry speech.

Anger is a powerful emotion to tap into. What does this mean for the voters? Researchers note that when watching the news, “people should pay attention to how politicians may try to appeal to or even manipulate emotions to get what they want.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Report About India ‘Spying’ on Journalists, Politicians Sparks Concern Over Illegal Surveillance