As COP15 Ends, ‘Biopiracy’ Is a Key Issue. What Is It?

Genetic information is key to conservation — but while this information is extracted from the Global South, the Global North benefits.

COP15, the UN biodiversity summit held in Montreal, Canada, has come to a close with the approval of a landmark deal with the ambitious target to protect 30% of the world’s biodiversity by 2030. While the summit was heralded as the “last chance” to protect species and ecosystems from destruction, previous reports suggested progress had been slow, with parties divided on the issue of financing conservation efforts. One key issue has been how to ensure a more equitable sharing of the benefits that arise from the use of genetic resources, that is, genetic materials obtained from plants, animals and microbes. Unequal benefit sharing leads to what experts call biopiracy. As The Guardian reported, an agreement has now been made on this front to set up a funding mechanism on digital sequence information (DSI).

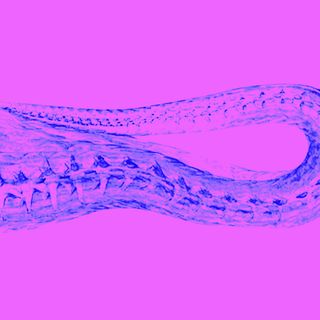

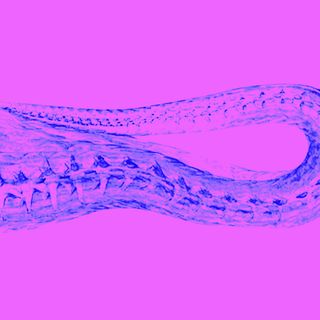

Firstly, benefit sharing refers to a system that aims to fairly distribute any benefits arising from the use of genetic information derived from natural resources between stakeholders — such as research organizations and biotech companies — and the countries where this biological resource is found.These genetic resources have led to various scientific breakthroughs over the years – from medicines to innovations in food and cosmetics. Technological advancements have now made it possible to digitize genetic data — digital sequence information (DSI) — and store it in online databases. This complicates the equal distribution of benefits.

DSI is made freely available in public databases to be utilized as a tool for scientific innovation that benefits populations around the world. For example, conservationists have used DSI to revive populations of the California condor, the largest bird in Northern America. However, countries from Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean have previously argued that open-sourced DSI “has become a loophole for pharmaceutical companies and others to avoid sharing profits deriving from their flora, fauna…,” reported The Guardian.

Here’s how that works. Researchers have often drawn from the traditional knowledge of indigenous communities to inform science. Instead of offering them due credit, however, the historical practice has been to patent their findings, which not only restricts access of the knowledge-holders to the research results, but also excludes them from subsequent benefits of the final product – both monetary and otherwise. This is biopiracy, which, as an article in The Conversation notes, “often accentuates power inequalities between wealthy, technology-rich countries and less affluent, yet bioresource-rich, countries.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Conservation Efforts Must Integrate Indigenous Perspectives

A France 24 report stated that genetic resources have historically been extracted by wealthy nations from biodiverse countries located predominantly in the Global South – an exploitative relationship that can be traced back to colonialism. Thus, there is a need for guidelines to strike a balance between ensuring the equitable sharing of benefits while still allowing for open access DSI to support research, as noted in an IUCN Issues Brief.

As a case in point, The Conversation highlighted the controversy between the French Institute for Development Research (IRD) and French Guiana. Researchers conducted interviews in French Guiana to identify local antimalarial remedies, publishing their findings in 2005. Ten years later, they received a patent for a compound derived from the plant Quassia amara. While the researchers had found the compound through alcohol-based extraction methods as opposed to the local distillation of the plant in tea, it was still the traditional knowledge of the locals that guided them to their discovery. While the matter was settled retroactively, with the IRD required to share benefits, both scientific and economic, arising from the use of the compound, the patent remained with the institute, “meaning it could still ban local communities from using the remedy.”

Over time, the right of countries to regulate access to their genetic resources has been recognized by the Convention on Biological Diversity. There have been previous attempts to govern access and benefit sharing at the international stage, most notably in the form of the Nagoya Protocol that aimed to provide “greater legal certainty and transparency for both providers and users of genetic resources.”

However, as a report in The Globe and Mail stated, the Nagoya Protocol only deals with genetic material that can be physically transported, such as a soil sample or plant specimen. As such, it does not account for genetic information in digital form, which bolsters biopiracy. The benefits from utilizing genetic resources are meant to go back to the country of origin. This is important for local conservation efforts, Pierre Du Plessis, a Namibia-based policy expert told The Globe and Mail.

Related on The Swaddle:

Only 3% of World’s Ecosystems Remain Untouched by Human Activities: Study

To overcome these issues, scientists have proposed a framework where access to DSI is “decoupled” from benefit-sharing, where “…payment would not be triggered by access to the databases but rather downstream at the point of commercialization or retail,” Dr. Amber Hartman Scholz, who is the study’s co-author, told Mongabay-India. This way, the scientific data can also be harnessed in a way that low-and middle-income countries that grant more access to genetic resources, receive more funds.

A union of African countries has also reportedly suggested a multilateral system where a 1% tax is levied on retail prices of all products derived from genetic resources, which could then be distributed to support conservation efforts around the world.

Vishaish Uppal, the Director of Governance, Law, and Policy at WWF India said at a press briefing, that the text emerging from the pre-COP15 Working Group meetings, that forms the basis for deliberations and decision-making at COP15, acknowledged that “benefits from digital sequence information on genetic resources should be used to support conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and that the main recipients of such benefits need to be indigenous people and local communities who are the custodians of resources and associated traditional knowledge.”

Still, there had been little progress, until now. This was summed up by du Plessis when he said earlier this year, “From an African point of view, we will not accept the adoption of the global biodiversity framework [without agreement on DSI]. It’s just an outcome too horrible to contemplate but if that’s what we need to do then that’s what we will do.” The decision reached at COP15 to set up a multilateral mechanism on DSI, including a global fund for equitable benefit sharing, has been hailed as a “historic victory,” according to The Guardian. Parties also decided to establish a “fair, transparent, inclusive, participatory and time-bound process to further develop and operationalize the mechanism,” details of which will be finalized at COP16.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

Human Bipedalism May Have Begun in Trees, New Study Suggests