As Indigenous Languages Die, India Loses Vital Means of Preserving Biodiversity

Local languages and rare vocabularies hold invaluable knowledge about the environment, nature, and history.

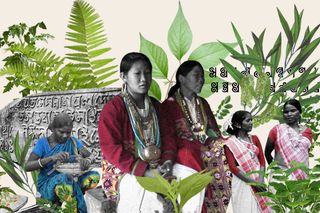

The Aka tribe in Arunachal Pradesh has its own way of treating fever and cough. The trick is to crush 10 grams of fresh leaves and stems of a plant called “Syowum” in the Aka language,strain it through a cloth, and apply it on the body. Although the medicinal plant has a scientific name, it is the native language that enables us to decode its secrets.

But the Aka language, also known as “Hruso,” faces an existential crisis. The language had less than 3,000 speakers in 2007, and its means of transmission is mostly oral. A language conservation project termed it as “endangered,” a linguist’s nightmare.

A similar fate awaits half of the world’s roughly 7,400 languages — some have vanished, some are disappearing, some remain undiscovered. A global project that looks at endangered languages chose the following tagline: “Every last word means another lost world.”

The pithy statement is accurate, in that language is inextricably tied to identity and culture. However, a less talked about aspect of language is its symbiotic relationship with biodiversity.

If biodiversity is a reflection of cultural plurality, linguistic diversity is the magic variant, the unsaid addition that determines how we preserve the ecology.

Loss of linguistic diversity leads to the disappearance of age-old medicinal remedies, wisdom about local biodiversity, and the ability to preserve nature and culture. This equation also gives local languages the key to mitigating — if not reversing — climate change.

The irony of this whole premise is evident: Dying languages hold the key to saving a dying planet.

***

“The disappearance of a language deprives us of knowledge no less valuable than some future miracle drug that may be lost when a species goes extinct,” Russ Rymer wrote in National Geographic in 2012. “… because their speakers tend to live in proximity to the animals and plants around them, and their talk reflects the distinctions they observe.”

Local communities use local languages to record their knowledge of ecology: which plants are toxic, which are dying, which have value; it also signifies their relationship with the plants, forest, water, animals, and land in words and phrases — a pattern that is vanishing now.

When small communities abandon their languages and switch to mainstream versions, “there is a massive disruption in the transfer of traditional knowledge across generations—about medicinal plants, food cultivation, irrigation techniques, navigation systems, seasonal calendars,” Rymer further explains. Arguably, language plays an irreplaceable role in culture and information dissemination.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Can We Understand a Language, but Not Speak It?

Abayneh Unasho, a lecturer of Biomedical Sciences, likened vocabularies to the “social genes” of a culture. If words were to become obsolete, not only will that erase cultural identities and history but also biodiversity conservation — “because life in a particular human environment is dependent on people’s ability to express the environment using words (cultural genes) of the language.”

Within India, linguists researched 780 living languages and estimated that 400 of them are at risk of dying. Think Dimasa in Assam, Birhor in Odisha, amongst others that are now under the threat of extinction. In 2019, researchers announced the extinction of five languages spoken in the Himalayan belt, as they only had 100 remaining speakers.

Preserving language is not only crucial for saving unique cultural products, but also for a utilitarian motive. “There could be a benefit to us from the thousands of different people around the world who have the most intimate knowledge of their natural environment,” Jonathan Loh, a research associate at the University of Kent in the School of Anthropology and Conservation, told Ecologise.

“The ways in which it is possible to survive in that environment, the ways in which different plants and animals can be used, how they’re caught or gathered or hunted, how they’re prepared or cooked or stored, or what uses they can be put to, whether they have any medicinal value—all of that knowledge, and this is a vast knowledge bank, is being eroded.”

A recent report showed the loss of linguistic diversity may lead to the disappearance of age-old remedies. Local communities have made use of natural elements, such as latex of plants to perhaps treat fungal infections, or the bark of trees to solve digestive problems, or even fruits for respiratory ailments. In India, research has shown that tribal groups in India use medicinal plants for combating diseases. The ancient Indians, for instance, used the snakeroot plant (Rauvolfia serpentina) about 3,000 years ago to treat several diseases from mental disorders to insomnia and snake bite; poppy juice (Papaver somniferum) to relieve pain and anxiety.

“The list goes on and on, it’s quite impressive,” Rodrigo Cámara-Leret, Ph.D., a biologist from the University of Zurich, wrote in PNAS. “Even the best plant taxonomists out there are amazed by the breadth of knowledge of indigenous cultures, not only about plants but also animals and their inter-relations.”

Language becomes a way of community preservation as well as identifying new species of plants and animals and furthering climate science. In Kerala’s Kattunaikka community, the word for a rubber species called is “Salu.” While the species was identified formally as Dioscorea tomentosa only in 2011, locals have known about its complexities and utility for decades. For instance, they know not to consume this on a daily basis because it leaves behind an itching kind of sensation — and eat this only during times of crisis like famine.

“The knowledge they have about the medicinal use of plants is uniquely encoded in a way that cannot be translated,” David Harisson, one of the founders of the language, tells Madras Courier.

The pronunciation, identification, associating each natural element with their belief systems make indigenous knowledge vulnerable to being lost in translation. “Usually, this information is passed from generation to generation. However, when a language declines, that knowledge system is completely gone. With the loss of language comes the loss of everything in culture and loss of solidarity, the loss of Man himself,” Ayesha Kidwai told Down to Earth.

When a language is threatened, so are these functions of biodiversity preservation. For one, it is widely recognized that 80% of the Earth’s biodiversity is found on indigenous homelands. Most of these languages are shared orally and do not have a written script — meaning most of these languages cannot endure over time. These languages dying out means the end of this knowledge.

Related on The Swaddle:

India’s Forests Expanded This Decade, Yet Indigenous Communities Are Still Being Forced Out: Report

***

Ironically, climate change and declining ecology also trigger the loss of local languages. This is because when those areas face a loss of plant and animal species, there can be similar extinctions in words, phrases, and entire languages.

“Language and culture support each other,” Stanley Rodriguez, speaker of Kumeyaay, one of the world’s most endangered languages, told The Revelator. He adds that the environment binds the two together.

Research has found a strong correlation between linguistic diversity and protecting biodiversity — most of the world’s biologically diverse spots that are threatened are also the ones where cultural and linguistic diversity is declining. More than 4,800 languages are spoken in areas of high biological diversity, a recent study in PNAS showed.

“In each place, the local environment sustains people; in turn, people sustain the local environment through the traditional knowledge, values, and practices embedded in their cultures and their languages.” Luisa Maffi wrote in the Index of Linguistic Diversity. The key, then, is to save indigenous people and their knowledge in order to save both the communities and their environments.

Acknowledging the link is also important to frame the worth of indigenous tribes and their inclusion in environmental preservation. The complex relationship between culture and nature can be understood in terms of statistics, numbers, utilitarian findings. But at its core is an unquantifiable relationship with the people that trumps all conservation efforts.

Research shows that communities that live closely and protect flora and fauna are more likely to be dependent on them for survival, so they will do more to protect them.

“The belief of Indian tribal peoples… that their culture was born and nourished in the forest, and their dependence for survival upon its continued existence has imbued in them a respectful attitude to nature, and given rise to the development of the most basic principles of forest management,” F.M. Strong notes.

Thus, the discovery of the Koro language in 2010 was exciting news for linguists. The language belonged to the Sino-Tibetan family, was spoken by less than 1,000 people living in an isolated Northeast region, and was the first known language from a region the linguists called a “black hole” for languages. For the first time, a way to articulate the local knowledge of the region emerged. Since then, attempts to preserve it have included speakers who have shared a range of videos and audios talking about medicinal plants and myths, aiding the longevity of their language — and the knowledge contained within it.

Other efforts to revive the connection with the languages include projects like Nat Geo’s Enduring Voices, which record oral languages that exist without a written script; keyboards that are using local characters; books published in local languages, such as Jharkhand’s Birhor.

When languages die, we lose people, civilizations, perspectives, ideas, and opinions. Most importantly, we lose unique knowledge and ways of existing. “The wisdom of humanity is coded in the language,” notes Lyle Campbell, director of the university’s Center for American Indian Languages. Language, culture, and environment are inextricably linked.

“Once a language dies, the knowledge dies with it.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

A Viral Disease Threatens India’s Honeybee Colonies, Impacting Beekeepers’ Livelihoods