The #MeToo Men Need a Course in Public Apology

If American comedian Aziz Ansari’s recent addition to the rapidly expanding genre is anything to go by, then this is the Age of the Public Apology. It is the predictable, and yet, unexpectedly cringe-worthy develop...

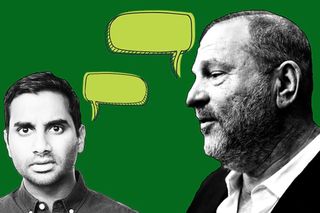

If American comedian Aziz Ansari’s recent addition to the rapidly expanding genre is anything to go by, then this is the Age of the Public Apology. It is the predictable, and yet, unexpectedly cringe-worthy development led by celebrities who found themselves at the wrong end of the #MeToo movement. The first big one to generate interest on social media was Harvey Weinstein’s public statement on 5 October 2017, and it is a fascinating study in the ‘art’ of apology. In it, he managed to set the bar for sincerity at an impressive low that many apologists after him, such as Kevin Spacey and Charlie Rose, have managed to bring lower still, in a rapid plunge that is only, perhaps, flattened by Roy Moore, the Alabama judge whose apology managed to dismiss summoning (as an adult) a high school girl over school intercom to ask her out on a date, as a “desperate attempt from the Democrats to sabotage the future of Alabama and the United States of America.”

Weinstein’s apology may sound better than that flat-out denial, and it certainly ticks off the six parameters of the ideal apology as suggested in the study “Negotiation and Conflict Management” by Michael A. Gross: an expression of regret, an explanation of what went wrong, the acknowledgement of responsibility, a declaration of repentance, an offer of repair, and a request for forgiveness. The overall effect, however, suggests Weinstein follows the letter, not the spirit of the word. His regrets and repentance are expressed in well-worn colloquialisms like, “I so respect all women and regret what happened,” and “this is a wake-up call.” In addition, he managed to misquote Jay-Z — “I’m not the man I thought I was and I better be that man for my children” — carelessly dragging in a male bystander into his own admission. His offer of repair and show of strength was to reference not just therapy, but the hiring of civil rights feminist attorney Lisa Bloom, and her “team of people.” He even made a strident attempt, (dedicating one-fourth of his apology), to show responsibility and paint himself among the righteous and good, as a man well deserving of being spared the ultimate disgrace – being shunned by liberals. After all, he was going to “channel” his “anger” at the two common enemies: the NRA and President Trump, and dedicate a $5 million foundation to women directors at USC named after his “mom” who he claims he will not let down. Perhaps the message being that, if mom can forgive him, why can’t these other women?

Beyond these attempts at misdirection, what really defined the tone of Weinstein’s apology was his opening statement or explanation for his behavior. “I came of age in the 60s and 70s, when all the rules about behavior and workplaces were different. That was the culture then.” You don’t need to be an expert in the field of apologies or psychology to know in your gut that there’s everything wrong with that lead. In fact, it’s the kind of misstep that psychologist and bestselling author, Harriet Lerner, who spent two decades studying apologies, illustrates well in her book Why Don’t You Apologize? The study opens with a quote from a New Yorker cartoon that shows a father talking to his grown son. “I wanted to be there for you growing up, I really did,” the dad says. “But I got a foot cramp. And then a thing came up at the store – you understand.” She goes on to say, that while the humor of the cartoon rests on its absurdity, “we have all received apologies followed by rationalizations that undo them. They are never satisfying. In fact, they do considerable harm…. ‘I’m sorry’ won’t cut it if it’s insincere, a quick way to get out of a difficult conversation, or followed by a justification or excuse.”

Celebrities, for better or worse, represent in some ways the ideal standard, and they are lighting rods for cultural trends and current norms. The power they yield over the public imagination is huge, particularly when they are social influencers such as actors, producers and creators. Their serious errors of judgment are beyond the personal, and when accused publicly, it is right that they respond in kind. As Lerner notes, “The need for apologies and repair is a singularly human one – both on the giving and receiving ends. We are hard-wired to seek justice and fairness (however we see it), so the need to receive a sincere apology that’s due is deeply felt.”

However, it is unfortunate that so many view the public apology as a space for deflection, denial, distraction and misdirection. It is when the apology admits to the crime, loosely speaking, that there is a sense of real reparation. While Ansari doesn’t belong in the ever-expanding rota of media celebrities who’ve sexually violated juniors in the working environment, his response to his disastrous date with the unnamed young photographer Grace is a good example of what a sincere apology looks like, whether private or public. He responded to her texted expression of unhappiness by saying, “I’m so sorry to hear this. All I can say is, it would never be my intention to make you or anyone feel the way you described. Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry.” Ironically, a legal analyst at Law&Crime notes that his apology — which he must have expected to be private — may just open him up for criminal liability and prosecution, if it is treated as an admission of guilt. Which may go some way toward a prediction that we can expect more cagey and unsatisfying apologies from public figures in the future. (Indeed, Ansari’s official public statement on the matter does not include a recognizable apology.)

This is the text Grace* sent Aziz Ansari after their date which left her feeling “violated”. She tells Ansari how uncomfortable he made her feel, saying “you ignored clear non-verbal cues” and “kept going with advances.”

In the meanwhile, there’s the very amusing online Celebrity Perv Apology Generator, that rehashes excuses, for example, “As someone who grew up in a different era, I feel tremendously guilty now that the things I did have been made public. At the time, I believed that my sociopathic manipulation of the 22-year-old in my office was consensual, and of course now I realize my behavior was wrong. In conclusion, I will not change anything about my actions or behavior.”

Jokes aside, what’s required in a litigious age may well be a diploma course for PR students in Public Apology. Until then, celebrities might be left wringing their hands, to quote Justin Bieber, “Yeah I know that I let you down/ Is it too late to say I’m sorry now?” Whether they really come to mean these apologies, and join the movement for a fairer society, is another matter.

Karishma Attari is a Mumbai-based writer, book reviewer and sunshine generator. She is the author of I See You and Don’t Look Down and runs a workshop series titled 'Shakespeare for Dummies.'

Related

The Buzz Cut: Serena Williams Spills about Motherhood, Comeback