Body Matters: How Non‑binary Patients Navigate Gynaec Offices

“When you enter a gynaec’s office, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a woman or not — what matters is that you are a female-bodied person.”

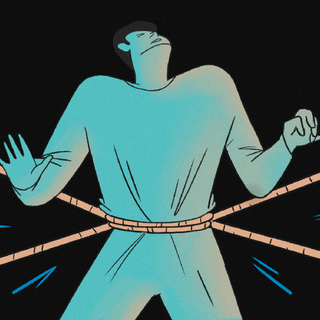

In ‘Body Matters,’ we explore the lived experiences of OB-GYN patients in India who defy stereotypical gender expectations, and challenge what it means to be a body that matters in medicine.

Gynecologists’ offices are some of the most gendered spaces in medicine — complicit in essentializing notions about womanhood, fertility, and femininity. When having certain bodily characteristics is implicit with cultural expectations around “femaleness” as a gender, people who require treatment but who are not women may experience compromised care. Two non-binary patients, G. and M., describe what it’s like to seek reproductive healthcare that is built on binary expectations. Dr. Sakshi Mamgain, a queer-affirmative and trauma-informed physician, explains why this happens and how medicine should adapt to center patient needs — no matter who they are.

When Doctors Rely on Gender Myths

G: I’m a non-binary polyamorous person with endometriosis. I needed a second opinion for my endometriosis and went to a reputed gynecologist in Pune. She asked me about my sex life, marriage, and partners — finally, she recommended pregnancy as a solution for my pain based on flimsy evidence. She couldn’t answer when I asked her for the proof (that endometriosis is cured by pregnancy). She then advised my mother that I should get pregnant by 35 to avoid complications.

M: I am a female-bodied person but I am not a woman. My non-binariness comes from a place of trauma and abuse. When the situation arises that I have to go to a gynecologist, it becomes difficult for me to accept this to myself also. When a doctor has to check if everything is fine, you have to let the doctor see [your genitals]. It can be overwhelming, even when you prepare yourself beforehand — the situation still poses many triggers. It takes a lot of time to get back to safety. I have vulvodynia. You have to visit a gynecologist if it is affecting your functionality so that you can rule out infections. In that case, I have to put myself through that situation again and again, and the pain increases more, there is a psychosomatic element there. They are looking at you as a “woman,” when they check for vitals and follow all the associated parameters… I understand that they’re speaking biologically.

I’m not a woman but I can’t distance myself from what my body biologically needs. But the language they use [is triggering]. I understand that they are well-intentioned, but when they see a female-bodied person, they will assume it is a woman. The problem is so deep-rooted and systemic, that we excuse them for misgendering us.

Dr. Sakshi: Healthcare professionals often don’t realize how the deeply rooted societal sexism sneakily finds its way into our medical spaces. Be it through the systemic gendered bias in our medical text or the unintentional ignorant remark in our clinical conversation, medical sexism is only a reflection of the bigger problem. In clinics, it is usual practice for a doctor to say that a female patient is just malingering or thought to be hysterical/emotional and therefore be dismissed, misdiagnosed, or not even given appropriate care. Unfortunately, most of the medical fraternity has not been able to break free of their cis-gendered and heterosexual perception of every patient that walks into their office; I wouldn’t even be able to begin to fathom the distress that gender non-conforming folks have to go through in hospitals. Medical sexism is making our facilities unapproachable and our patients sicker. Doctors are still performing non-consensual and unnecessary surgeries on intersex infants and children so they conform to the gender binary anatomically. We fail our patients when we fail to respect their bodily autonomy.

When Clinical Procedures and Spaces Induce Dysphoria

G: I never told any gynecologist about my gender. The conversations create dysphoria and a lot of anxiety. The doctor’s advice about pregnancy, moreover, validated conversations at home — when a doctor tells my mother something like that, it validates her demands [pertaining to conventional gender expectations] from me as well and increases my distress. These things delay diagnoses for many queer and trans people. I have a friend who is trans, he is under hormonal therapy and dealing with excruciating menstrual pain, but is unable to seek medical help.

M: I know who I am not, but I’m leaving space for myself to understand who I am. When you enter a gynecologist’s office, it doesn’t matter whether you’re a woman or not — what matters is that you are a female-bodied person. When you are called a lady or a woman, or if someone else is filling a form for you and there’s no other option other than Mrs. or Ms., When you enter the clinic itself, that is where it starts getting overwhelming. You know this is just the first step and is only the tiniest step; after that, there’s the unsolicited advice, the dysphoria that kicks in, this happens even with the most sensitive practitioners. An informed practitioner obviously helps a lot, but the experience [of pain] is still there.

One advise to practitioners: please don’t assume, please don’t give unsolicited advice, and please know your limits and boundaries. More often than not when you go to a gynecologist, they talk to me as if I am a child and they are my well-wishers… But when they take on that role, those assumptions [telling me my sexuality and identity instead of asking] are something they can do away with.

Dr. Sakshi: From school grade biology, we are only taught about gender as a binary. We are taught that the antonym of a man is a woman. Quite obviously, the vast majority of our healthcare professionals also carry the same notion further into life and fall short of perceiving gender and sexuality as a spectrum. Conversations around queer and trans health have only very recently been ignited in the country. For the cisgendered heterosexual community in medicine, there is no other way but to include a mandatory sensitization program in our medical curriculum.

When Identities Are Invalidated

M: When I went to my regular physician for a urinary tract infection (UTI), I kept getting called “young lady” despite me asking them not to. They took it as a joke. After a point, I didn’t say anything because I was scared that my care would be compromised — not realizing that my care was already being compromised. My general practitioner (GP) then said that my trauma would affect future pregnancies if I don’t address it now. The doctor was also implying that I was “sticking to labels” when I told them about my asexuality [not realizing that my sexuality and identity come from a place of trauma]. The doctor had no reason to comment on my sexuality, motherhood, and so on when I was there for a UTI. After that, I did not visit my GP at all.

Dr. Sakshi: As doctors, we are taught about empathy and about having a non-judgemental eye for all. So, if we could do just the bare minimum: introduce ourselves with our pronouns, talk in a gender-neutral language, regard the patient’s privacy, be sensitive to their needs, explain every physical examination, talk them through a procedure while at it, and encourage regular visits and check-ups; it would reform the healthcare experience for the LGBTQIA+ community.

While we bring our medical fraternity up to pace on queer-affirmative and trauma-informed care, we could really use some advocacy for policies to be patient-centric. We need systemic societal and governmental action to correct gender discrimination in healthcare.

The above insights were obtained from two anonymous patients and one doctor — all of whom had vital things to share about what the doctor-patient relationship should not look like, and a roadmap for what it should look like. The narratives here are as told to The Swaddle, and are preserved for maximum authenticity of lived experiences. They have only been edited and organized thematically for the sake of clarity and conciseness.

Related

Why Some Lifelong Smokers Don’t Develop Lung Cancer