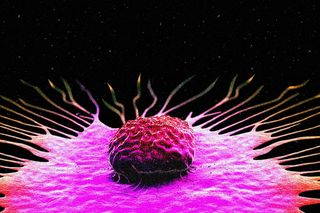

Breast Cancer Spreads More Aggressively at Night, Finds New Study

The research has implications on how cancer is monitored and treated.

A new finding about breast cancer has left scientists perplexed. Cancer cells may spread more efficiently at night, when the body is at rest and the person is sleeping.Researchers call this a “marked acceleration” in the way breast cancer metastasizes, or spreads in the body. This pattern of spread holds important implications for both the breast cancer diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

“When the affected person is asleep, the tumor awakens,” said lead authorNicola Aceto, professor of molecular oncology at ETH Zurich.

Published in the journalNaturelast week, the research offers “startling” clues about identifying and further treating breast cancer, which remains plagued by a lack of timely and appropriate diagnosis. “If doctors detect breast cancer early enough, patients usually respond well to treatment. However, things become much more difficult if cancer has already metastasized. Metastasis occurs when circulating cancer cells break away from the original tumor, travel through the body via blood vessels, and form new tumors in other organs,” the researchers at ETH Zurich explained. Notably, breast cancer accounts for 14% of cancers in Indian women, and experts have observed a higher caseload in recent years whichmakes monitoring breast cancer a key piece of cancer treatment practices.

It begs the question: when does the tumor shed metastatic cells in the body?

The answer was borne by observing an irregularity. Researchers scrutinizing breast cancer cells in mice, at first, observed a peculiar trend: the tumor cells in circulation differed when analyzed at different times of the day. The said mice with a higher number of cancer cells were also those sleeping during the day, when the samples were collected. The researchers from ETH Zurich then looked at breast cancer in 30 women, a small data set, including 21 patients with early breast cancer and nine with stage IV metastatic cancer. The researchers went on to replicate this experiment four more times on different mouse models of breast cancer, again sampling the blood while the mice rested during the day and were active at night.

The blood samples presented a “striking and unexpected pattern.” A higher number of tumor cells (78.3%) was found in samples taken at night, as compared to blood samples drawn during the day.

The cancer cells collected during the rest period were “highly prone to metastasize, whereas circulating tumor cells generated during the active phase are devoid of metastatic ability”, the study noted. Evidently, then, cancer cells that were more in circulation during sleep cycles were also more aggressive.

Related on The Swaddle:

Novel Breast Cancer Vaccine To Go Into Clinical Trials

What explains this discrepancy? It may have something to do with disrupting the body’s circadian rhythms, and the hormones this cycle regulates. “…the escape of circulating cancer cells from the original tumor is controlled by hormones such as melatonin, which determine our rhythms of day and night,” said Zoi Diamantopoulou, the study’s first author and a molecular oncology researcher.

How does this change things? For one, it has a bearing on something as seemingly trivial as when the blood sample is collected. If the findings are true, a sample collected during the day may not present the most accurate picture of metastasized cancer cells.

“In our view, these findings may indicate the need for healthcare professionals to systematically record the time at which they perform biopsies,” said Aceto. “It may help to make the data truly comparable.”

There is a need for more research to ascertainjust how much time canaffect diagnosis. Moreover, it is important to understand if the aggression observed among cancer cells applies to all cancers, and if a similar trend is observed in a larger dataset.

This is not easy. NYU Langone Medical Center cancer researcher Thales Papagiannakopoulos, who did not participate in this study, told The Scientist of the challenges in teasing out the modulations of when cancer cells metastasize. He theorizes that there may be an immune-related force at play along with hormones, but it is too early to say.

For now, researchers are looking into cancer progression, the current cancer therapies, and if adjusting the time of treatment in itself can change patient outcomes. According to Qing-Jun Meng, a University of Manchester chronobiologist, who was not involved in this study, a more nuanced exploration around time and testing can “open up new opportunities” for targeted treatment.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Why We Talk to Ourselves, According to Research