Bro‑y Directors Can’t Be Our Only Defense Against Marvel

Amid criticisms of Marvel taking over cinema, a crop of auteur filmmakers have emerged as the vanguard against it — but they’re part of the problem too.

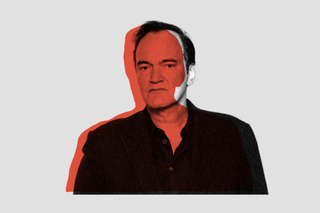

Quentin Tarantino will never work on the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). The 59-year-old American director behind some of the greatest movies of the last thirty years recently expressed his strong distaste for the Disney-owned cultural behemoth, reported Variety on Tuesday. At an earlier event this month, the filmmaker had also mentioned how it would be difficult for him to helm a Marvel project, given that one has “to be a hired hand to do those things.” The director stated that he wasn’t someone “looking for a job.” Criticizing Marvel’s omnipresence in the cinema industry — with many workers contributing to the industry — Tarantino noted that Marvel movies seem to be “the only things that seem to be made.” He further noted, “they’re the only things that seem to generate any kind of excitement amongst a fan base or even for the studio making them… And so it’s just the fact that they are the entire representation of this era of movies right now.”

Tarantino, with his public displeasure of Marvel, joins a long list of distinguished directors who have criticized the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its omnipresence in present-day cinema. The most famous of them, of course, is veteran filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who had famously opined that MCU movies were more akin to theme parks than cinema. Other illustrious directors sharing sentiments similar to Tarantino and Scorsese include Francis Ford Coppola, Bong Jon Hoo, and Alejandro González Iñárritu. These filmmakers with their criticism have almost formed an informal, vocal vanguard against the proliferation of Marvel movies, with the cinema-loving audience celebrating the responsibility these filmmakers have voluntarily taken up to preserve authentic “cinema.” However, a closer look at these directors’ defense of “real cinema” suggests that they might be part of the problem.

These filmmakers — modern-day greats known for their distinct visual language and cinematic style — have often criticized the Marvel model for not being real cinema, or for being cinema for kids. While criticism of the franchise model and its oversaturation is valid and much needed, the language filmmakers have often adopted in their criticism has often been one of condescension toward the MCU — and by insistence — of its several fans spread worldwide. At the same time, they have often either chosen to ignore some valid criticisms against their own work or argued that the criticism wasn’t cinematic enough.

Tarantino, for instance, has often reacted dismissively against the frequent use of the n-word in his films. In a recent talk-show, the filmmaker suggested that audiences who had a problem with the use of the racial slur in his films should probably watch other kinds of movies. “If you have a problem with my movies then they aren’t the movies to go see. Apparently I’m not making them for you.”

In the past, Tarantino alleged that the resentment against him for using the n-word in his films while trying to authentically depict the lived experiences of black people just because of his own whiteness was “the heart of racism,” maintaining that he had the “the right to tell the truth.” Spike Lee, the black director known for his work on black American experiences, has questioned and criticized Tarantino’s use of the n-word as an “artistic liberty,” noting in a tweet referencing his film Django Unchained that “American Slavery Was Not A Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western.”

Tarantino isn’t the only filmmaker who has sprung up as a defender of cinema while reacting strongly to criticisms of their own work. Take the case of Scorsese, for instance, who in his 45-year-long career has almost exclusively made movies on White Christian men. While a champion today for more representation and diversity in cinema, Scorsese’s own works have hardly followed suit, with only a couple of films that had a strong woman character, and none that put a person of color in the forefront. In a 2019 interview, the 82-year-old director commented that he would love to write more strong female characters, but noted that at his age he “doesn’t have time anymore.” The director noted, “If the story doesn’t call for it, then it’s a waste of everybody’s time.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Franchise Filmmaking Is Taking Over the Cinematic Medium — But at What Cost?

Beyond these individual criticisms on representation and sensitivity, however, there is a deeper issue at play at a vanguard of male directors self-appointing them as gatekeepers of cinema. These filmmakers’ almost dogmatic definitions of what brands of filmmaking qualify as “cinema” and what qualifies as “kid’s movies” or “theme park attractions” is also related to the matter of taste, and the class divide between highbrow and lowbrow art. It is a divide that is often dictated by class interests, and one that is often used as a marker of the intellect of the audience. Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist who described the multiple forms of capital, wrote that taste is “a class culture turned into nature, that is, embodied, helps to shape the class body.”

Taste is a highly subjective matter that is often shaped by the social circumstances one finds themselves surrounded by. To then denigrate an entire style of filmmaking — albeit built through massive commercialization and attractive, crowd-pulling marketing — without engaging respectfully with its audience is to implicate the audiences as equally responsible for the degrading state of cinema in the present day. It does not take into confidence those who are engaging and endorsing this brand of filmmaking.

Moreover, brushing off any style of filmmaking that doesn’t agree with one’s vision in broad strokes is dismissive of the nuances that may exist even when it is largely dictated by purely commercial interests. Simu Liu, the actor who plays the Chinese-American superhero Shang Chi in the MCU pointed out to the Guardian while reacting to Tarantino’s comments, “If the only gatekeepers to movie stardom came from Tarantino and Scorsese, I would never have had the opportunity to lead a $400 million plus movie.” Liu further noted, “I loved the ‘Golden Age’ too… but it was white as hell.”

Despite being dictated largely by commercial interests, movies like Black Panther and TV shows like Ms. Marvel managed to connect emotionally with minority audiences in the US and worldwide. Even as an exercise in the appropriation of minority cultures and representations by a studio run by white people, these experiments resonate more with people than a male white director complaining of racism when asked to not use the n-word in their films.

Filmmaking is never an individual art. Cinema is a collective, communal medium, almost never made or viewed by just one person. It is thus natural that there will be more than one brand of filmmaking that will exist, and given the diversity in the world, there will be different styles that will influence and resonate with different people. Hence, it is not just difficult, but also undesirable, to have set standards and definitions of what qualifies as good cinema or bad cinema.

It is true that the entry of market forces, and the prioritization of profits over content, is a cause of concern for any art form. The focus on studying and taming markets often generates formulae and kills the diversity of creative thought. At the same time, however, aggressively defining the parameters of what qualifies as art and what doesn’t also tends to create a different set of expectations around which films deserve to be watched and enjoyed and which films do not, alienating audiences from their personal engagement with and discovery of their taste. This alienation will eventually only contribute further to the popularity of market-guided studios.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Words Mean Things: ‘Gaslight’