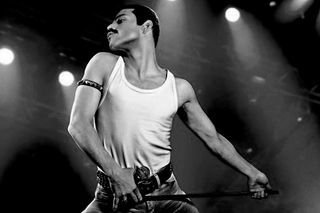

‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ Frames Freddie Mercury’s Queerness as His Undoing

The biopic’s depiction of his sexuality misses the mark entirely.

Bohemian Rhapsody, the biopic about Freddie Mercury and the meteoric rise of Queen, mishandles Mercury’s sexuality, and its impact on his work — completely. Rather than portray the lead singer with any nuance or complexity, the movie chooses to pit Mercury-the-virtuoso, against Mercury-the queer man. Capitalizing on the way his sexuality influenced his persona, while demonizing his identity, does a disservice not just to the memory of Mercury, but to queer people everywhere.

An integral scene just before the climax sees Mercury, played by a commendable Rami Malek, living in his studio in Munich. Paul Prenter (Allen Leech) has deceitfully convinced Mercury to leave the band and go solo, isolating him from his friends and supplying a steady flow of booze, drugs, and leather-clad men (all in a red-hued daze as ‘Another One Bites The Dust’ plays in the background). Mercury’s old friend and lover, Mary Austin, comes to literally save him from the drug den, begging him to come back home to the people who really care about him, i.e. his straight, cis, white band mates and her. She leaves Mercury standing dramatically in a downpour, as he finally tells Paul he wants him out of his life. The moment is strangely puritanical as Mercury asks in disgust, “Do you know when you know you’ve gone rotten? Fruit flies. Dirty little fruit flies coming to feast on what’s left. So fly off.”

This is the only time we get a glimpse of how Mercury’s exploration of his sexuality might have played out — through raucous parties, blurry camera work, and with the obvious implication of drugs being involved. In direct contrast is the first half of the movie that portrays Mercury’s relationship with Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton) as wholesome and pure, representing a kind of love and acceptance that the British Asian man had craved his entire life. Mercury’s relationship with Jim Hutton, his partner for the last seven years of his life, is reduced to a single, cursory kiss onscreen towards the end of the film. In fact, at no point does the director, Bryan Singer, portray any kind of queer intimacy.

All we see is a Mercury who is terribly lonely, despite his talent, because, alas, he is queer and therefore denied the comforts of family life. But rather than explore what it means to be discriminated against and further marginalized, Mercury’s sexuality is set up as just another way fame corrupts him. The promiscuity and sordid affairs — which are used to define his queerness in the film — are positioned as detractors from his music, just another addiction he must overcome.

It’s difficult to see Mercury’s HIV diagnosis, after his time in Munich, as anything but a kind of retribution. The film manipulates timelines to make Mercury tell his band mates about his illness just before their climatic Live Aid concert in 1985 (in reality he received his diagnosis two years later), as if this was his wake-up call to abandon his perverse back-room romances and focus on his music instead. The minutes dedicated to reenacting this concert are arguably the only enjoyable ones in the film. Malek taps into some primal energy and exudes all of the magnetic eroticism of Mercury onstage, taking us through hit after hit, although the lyrics flashing at the bottom of the screen hardly warrant a sing-a-long in the same way that say, Mama Mia would. Instead you just want to sit back and watch the fantastic performer that Mercury really was — arguably though, going home and watching that performance would have the same effect.

Freddie Mercury was a glam rock, genderbending, British Asian musician and queer icon, at a time when homophobia and racism was rampant. The fact that he wasn’t able to be entirely open about his identity during his lifetime is even more of a reason why this film should have finally portrayed him in all his complexity. Instead, we get a hollow, cautionary tale of a musician who is punished for his fame and flamboyance, despite his talent. Freddie’s queerness is relegated to those good old tropes of sex and death, rather than affording him any kind of nuanced personhood. The world loved Freddie Mercury’s flamboyant style, disregard for convention, dynamic performances, and ability to appeal to “the misfits,” in his words. To pit a part of his identity against his art is to misunderstand him completely.

Nadia Nooreyezdan is The Swaddle's culture editor. Since graduating from Columbia Journalism School, she spends her time thinking about aliens, cyborgs, and social justice sci-fi. She's also working on a memoir about her family's journey from Iran to India.

Related

Students Shouldn’t Sacrifice Maths and Science for ‘Scoring Subjects’