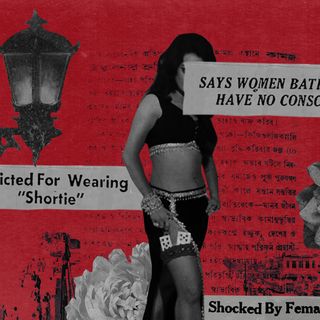

Can We Move On: From the ‘Happily Ever After’ Trope That Doesn’t Include Unconventional Paths to Happiness

What’s the point of a happy ending for all if it’s tailored to a narrow vision of what a fulfilling life looks like?

In Can We Move On, we revisit old tropes and question whether they have any remaining cultural relevance.

Perhaps the worst time to pick on a “happy ending” trope is during a worldwide pandemic where people desperately need moments of levity. Yet, here we are, ready to call bullshit on the endless iterations of happily-ever-afters strewn across Bollywood since… forever.

The importance of a happy ending is clear — lovers reunite, families make up, and villains die. Beyond this element of closure, a solid piece of entertainment leaves the audience satisfied, the money they spent on tickets and snacks was indeed worthwhile.

Of course, climactic endings don’t happen the same way every single time. There are at least seven different types of happy endings, according to the website TV Tropes. These range from the “Shock-and-Switch Ending,” in which a bad ending is transformed into a happy one for shock value (Get Out, 2017); the “Earn Your Happy Ending,” where the elusive happy ending comes after a feature film’s worth of darkness and angst (The Dark Knight Trilogy); “Happily ever after” ending insinuating that everyone involved has a future life drenched in joy. Also, these “Happily ever afters” are invoked via romance, vanquishing villains, and matrimony — in that specific order. Variations of any kind have little room in comfortable, cyclical space.

What’s another thing in common with many of these happy endings? They’re tailored around the happiness of the male protagonist or other male characters. In Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999), Nandini chooses Vanraj over her longtime love Sameer because Vanraj is the better, more devoted partner. In Jab We Met (2007), feisty Geet chooses Aditya over her longtime love Anshuman. Even in Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani (2013) — a film tailored to make the female protagonist’s dreams come true — the hero tells Naina that they will travel the world together to follow his dream, though she wants to stay home. Hell, even in risk-taking, subversive Manmarziyaan (2018), Rumi chooses her sweet, kind husband over a fiery affair.

And while each plot had a million strings attached, the woman always ends up with the ‘right’ (socially acceptable) man.

We know that a trope is a writer’s tool to respond to, control, or subvert audience expectations — but it also informs audience behavior. Some tropes tell moral lessons, others brand individuals, and omnipresent tropes like happy endings create a template for a life to look forward to. When these happy endings are tailored to keeping the man happy, it informs women that their happiness is their male partner’s happiness — which may be true sometimes, but also overwhelmingly untrue in other cases.

Related on The Swaddle:

MAMI Films Highlight Women’s Negotiation With Freedom Through Love, Sex and Desire

Happily-ever-after motifs also push women to further internalize that their joy lies in marrying men within or above their social class. It is no coincidence the only objection to many of Bollywood’s love stories is that these matches are “love” matches, as compared to the more virtuous alternative of arranged matches. It’s also not a coincidence how many inter-caste, inter-religion, or even inter-class love stories portrayed on screen end tragically. Via these tropes, writers tend to infuse their own biases of the world into the audience’s minds, keeping the status quo going.

The prioritization of male happiness and control, in both real and reel life stories, is also showcased by who pursues whom. When men pursue women or prove their affections to women, all is well. However, when women pursue men, women’s behavior is seen as strange — even pathetic. In Jab We Met, Geet chooses to send herself into exile after her pursuit of a man leads to brutal rejection. In Yeh Jawaani Hai Deewani, Naina chooses to wait for years till the love of her life asks her out. In the end, a trope centered around happy endings also creates a restricted idea of one’s aspirations, denying the characters the freedom to choose their version of happiness.

The possibilities for women beyond the social construct of happiness are endless. Instead of rigid conventions like marriage, families, and children, women could find joy solo, childless, in their careers, in volunteering, or in anything they choose. The trend is evident in India, with women (mostly urban) choosing to avoid marriage, childbirth, and choosing premarital sex, divorce, and their careers. The same is also possible for men — their happily ever afters do not always require the presence of family and joy.

Mirroring real life, some films do attempt to showcase these non-cisheteronormative paths. Films like Ek Ladki Ko Dekha To Aisha Laga (2019) and Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020) subvert the boring, old happily-ever-after trope. Queen (2013) shows a woman walking away from an engagement after traveling alone. English Vinglish (2012) shows a housewife making new friends while learning a new language without familial support.

The happily ever after trope simply won’t die — and it shouldn’t — because we all deserve the possibility and promise of a life full of joy. But the fact that this joy is granted on terms framed by society is frankly dull — even poisonous. It’s time to frame a happily ever after story for inter-caste couples, for couples from different faiths, and for couples who don’t care to be couples anymore.

Maybe we won’t move on, but we definitely expect better.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

The Buzz Cut: Today Marks 21 Years Since the Iconic ‘Saas Bahu’ Show Started Running