Can We Move On: From the Trope of the Man Whose Violence Is Justified Because His Partner, Sister Was ‘Wronged’

The trope suggests that it’s okay to assault — or even kill — someone if their actions violate our ethics.

In Can We Move On, we revisit old tropes and question whether they have any remaining cultural relevance.

What is common between 2014’s Ek Villain and 2019’s Marjaavaan — besides Sidharth Malhotra essaying the part of the male lead with an emotional range comparable to that of wooden planks? Well, both the movies — alongside countless others — have “Women in Refrigerators,” albeit not literally. It’s shorthand for a sexist trope that the fictional universe refuses to retire. Also called “fridging,” it refers to female characters being assaulted, murdered, or even raped — and often, subsequently disposed of — simply to propel the male lead’s narrative arc of righteous revenge, realized through violence.

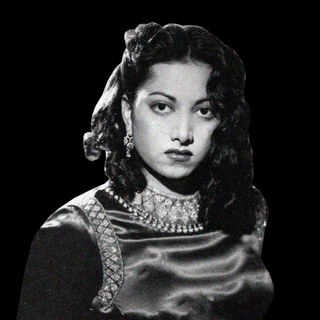

Discussing the roles she had been offered after the success of 1994’s Hum Aapke Hain Koun, actor-director Renuka Shahane said last year that she was told, multiple times, “[A]ap iss hero ki behen ho [you are the hero’s sister] and you are the catalyst because you get raped and the hero feels that he should take vengeance against the entire world and whoever the villains are.”

2015’s Angry Indian Goddesses employed a meta-textual reading of this trope to highlight Bollywood’s obsession with fridging. Amrit Maghera’s character, Joanna Mendes, who plays the part of an actor, is shown shooting for a movie — within the actual movie, of course. “[The movie], exemplifies how contemporary Hindi cinema is attempting to disrupt cultural scripts of femininity and Indian womanhood… [She] appears as a typical village belle wearing [a] ghagra choli, kidnapped by goons and crying out for the hero to save her, satiriz[ing] Bollywood’s long tradition of casting women as the perpetual ‘victim,'” writes Isha Karki in a 2019 paper published in the Journal of International Women’s Studies.

Instead of abiding by the script, however, Joanna persistently attacks the perpetrators, much to the chagrin of the fictional director. Adding another layer of subversion is when Joanna is actually raped in the movie — and there is no man who emerges to avenge the crime.

Related on The Swaddle:

Can We Move On: From the Trope of the Male Savior Who Rescues Women From Patriarchy in ‘Woke’ Movies

The mere existence of the movie might suggest that Bollywood acknowledged its blatant misogyny, and decided to do better by its female characters — instead of sacrificing them as an excuse to serve “dhishoom dhishoom” thrills to charged male audiences. But nothing can be further from the actual state of affairs. Just two years after the release of Angry Indian Goddesses, came yet another rape-revenge drama named Kaabil in 2017.

Here, “Supriya [played by Yami Gautam] is raped twice in the film, and both the times, the focus has been on how Rohan reacts to the crime, ignoring Supriya’s personal trauma and her attempts at living a normal life… The focus is then on how Rohan [her husband, played by Hrithik Roshan] becomes silent and withdrawn… In all this, Supriya’s voice, her coping struggle is lost. When she is made to undergo the same trauma for the second time, she chooses to ‘sacrifice’ herself to spare Rohan the agony (of what, I fail to understand),” Simran Vijan wrote in 2010. Following this, of course, the narrative shifts its focus solely on Rohan’s vengeance — making it clear that Supriya’s trauma was but a plot device to justify his machismo-infused eyeball-grabbing action scenes, and boost the sales of a video game based on Kaabil‘s plot.

In 2008’s Ghajni, and a decade later, 2018’s Simmba, characters played by Asin Thottumkal and Vaidehi Parashurami are conveniently killed off to trigger new chapters in the lives of characters essayed by Aamir Khan and Ranveer Singh respectively. Given that both Khan and Singh are leading male actors in an industry as patriarchal as Bollywood, female actors rarely get characters as meaty — or even as much screen-space — as in movies with the duo at the helm. Granted that’s an entirely different concern, but somehow the element of “sadiomasochistic scopic pleasure,” which often accompanies the trope, makes its foray into the 21st century downright infuriating. Here’s why: it uses women’s trauma to draw in audiences only to discard the women and disegard their agency in favor of pivoting the narrative to the glorification of the “righteous” savior’s “courage” and “determination.”

“Though the victim endures the violence, it is the vigilante savior who gets to decide the type of justice the victim gets,” Aditi Murti wrote in The Swaddle last year, adding that it fuels the “complete lack of interest in [the] well-being of [survibors] after the perpetrator is ‘punished.’ The punishment seemingly ends the entire saga, but the victim never receives what they really require: an apology and acknowledgment of the wrongs from the perpetrator.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Tell Me More: Talking Accountability and Transformative Justice with Deepika Bhardwaj

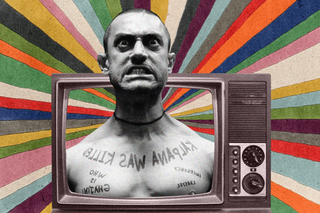

The formula, evidently, works — resulting in over 35% of the crimes portrayed in Bollywood films between 2016 and 2019 being vigilante killings; rapes were under 10%, and non-vigilante murders and kidnappings, about 20% and 10%, respectively, according to a study.

Murti noted that the rehashing of sexist tropes hinged on the sufering of women tend to promote the idea that “women are not in charge of their own narratives” — in addition to boosting acceptance towards violence and encouraging people to take the law into one’s hands, of course. “The audience isn’t ready to engage with what women have to say about their own distress, because revenge and virtue fantasies built from women’s pain is a norm for Bollywood entertainment …men want to see their heroes take power into their own hands and right the wrongs in the world. That, according to the male narrative, is the only vital importance of showcasing women’s trauma,” she added.

But misogyny isn’t the only problem with this trope; it’s justification of violence as “righteous” — arguably, an extremely subjective assessment — presents yet another risk in a country that has fallen prey to divisive politics at present. To make matters worse, it’s hardly a secret that threats to the “honor” of women surface far too often in communal politics. So, given how the persistent trope has conditioned men to react to women’s trauma –imagined, threatened, or otherwise — by unleashing testosterone-fuelled brutality, its implications could be dire. “Love jihad,” for instance, a spawn of Hindutva-vigilantism, that has resulted in the perpetration of violence by men who believe they are “protecting” women, is a terrifying example.

Perhaps, then, it is time we retired this sexism-spewing, violence-excusing scope. And so, the question: can we, please, move on?

Devrupa Rakshit is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She is a lawyer by education, a poet by accident, a painter by shaukh, and autistic by birth. You can find her on Instagram @devruparakshit.

Related

The Buzz Cut: Award‑winning Actor Makes Film Festival Jury, Men on Twitter Doubtful of Her Qualifications