Cancel Culture Is Not Making People Intolerant; It’s Empowering Them

How else will marginalized groups, whose needs are often overlooked in mainstream culture, have their voices heard?

Cancel culture, otherwise defined as “consequences,” according to a popular online joke, is a social media phenomenon wherein progressive social media users attempt to chip away at the cultural capital or professional clout of a celebrity who says or does something offensive (casteist, racist, sexist, queerphobic) by ‘cancelling’ them.

One of the main critiques of cancel culture is that it’s making people more intolerant, quick to judge and banish those who even slightly disagree with them. Critics of the cultural phenomenon say cancel culture doesn’t leave any room for constructive discourse because social media users often deliver a quick verdict, based on a snap judgment, to a celebrity they perceive as offensive — leaving no opportunity for the ‘cancelled’ person to explain themselves and make their case against their own ‘cancellation.’

The cancel culture debate often resembles a tug of war between those trying to make room for discussion between people with opposing viewpoints and those not wanting to compromise their principles by engaging with a celebrity they view as problematic. But people tend to forget — whether a celebrity is canceled or not is largely up to the celebrity themself, not on those wanting to cancel them.

Take Ellen DeGeneres, for example: When photos of her at a sports game with known homophobe George Bush went viral on social media, her fans started calling her out for being a hypocrite — supporting gay rights herself but also fraternizing with a former politician who actively advocated for people like DeGeneres not to have civil rights. The social media users called her out. But when DeGeneres addressed the controversy on her show, she advocated for universal kindness while herself brushing off her critics to be a bunch of over-sensitive Twitter snowflakes. Those of her fans who didn’t agree with her choice to be friends with Bush realized she wasn’t open to criticism, and slowly but surely, their call-outs turned to demands to cancel DeGeneres and her show. Others who didn’t have much of a problem with her — this faction makes up the majority — have continued to prop up her celebrity, and she stays untouched by cancel culture.

But those engaging in cancel culture aren’t an unreasonable, intolerant sort. Take Jameela Jamil for example: the actress says one or more un-woke thing every other day, but when called out, she admits to being a feminist-in-progress, profusely apologizes for her misstep, and promises to be better. In doing so, she stalls the progression of people calling her out to them wanting to cancel her. It’s the nature of public introspection and apology that the celebrity engages in when called out by fans that often determines if, and for how long, they’re cancelled.

Take Kevin Spacey, on the other hand, who was immediately canceled — from his fandom and from his television show House of Cards — after allegations surfaced of him having made sexual advances toward a 14-year-old boy. Spacey released a YouTube video donning the personality of his character Frank Underwood from the show, telling his fans they shouldn’t believe the allegations, that he was essentially telling them he was unfairly canceled and that he would be back. Every year, he releases a similar video, never seeming to publicly express remorse or reckon with what he was accused of. He stays cancelled.

But, Jamil and Spacey are exceptions on either end of the cancel culture spectrum, so to speak. Most celebrities who are called out, or whose fans want to cancel them, end up like DeGeneres — defiant and uncancelled. Louis C.K. bounced right back after being accused of sexual harassment by several women — so much so, he now jokes about said allegations to rooms full of his fans. Kevin Hart, after tweeting a homophobic joke, had to step down from hosting the Oscars, but still enjoys the support and adulation of millions of fans worldwide. Sadly, cancel culture, for all the brouhaha around it, doesn’t really accomplish much. At the least, celebrities who have offended a minority group get some flak on social media and may lose a couple of followers (Priyanka Chopra after she was confronted for her support of the Indian military). At most, they are effectively canceled for a short while … until they’re miraculously not, suddenly being welcomed back with open arms and pats on the back for having survived the time of penance (Aziz Ansari, Louis C.K., Tanmay Bhatt).

So, why do people still try? Most of the time, the problematic action of the celebrity is at the expense of a group of people, be it fat people, queer people, black or brown people, or women — from Kevin Hart tweeting that if his son played with his daughter’s dollhouse, he would break the toy over his son’s head and tell him to stop being gay, to Azealia Banks calling Zayn Malik a “curry-scented bitch.” When influential celebrities, often pop culture icons to many, off-handedly say a racist, homophobic or sexist thing, for example, fans can find it disheartening and experience a solidification of the hate rhetoric that they most likely face in everyday life. Then, an offhand comment by a celebrity doesn’t remain benign; it adds to a culture of marginalization people of color, queer people and women face every day. In trying to cancel them, the people directly targeted or affected by the celebrities’ conduct exercise their right to be heard, which would otherwise be violated.

Too often, people from marginalized communities have to wait for the rest of society to be tuned into their needs. In social media, many find a more democratized space within which they can freely express their opinions without having to wait for their majority counterparts to catch up. For celebrities who offend them, it’s important to remember that second chances are earned and that minority communities owe them no debt to either forgive or engage in discourse. By putting the celebrity’s needs centerstage, the critique of cancel culture not only fails to hold the powerful accountable, but also seeks to maintain a dynamic of power hierarchy.

If a lack of engagement and influence is a (phantom) consequence of cancel culture, then the marginalized groups have been cancelled in reality since time immemorial, simply by virtue of their existence. The people who are at risk of being canceled are fine. Nothing is going to happen to them. Most of those trying to voice their opinions, however, have never been fine. To paint their pushback against intolerance as intolerant is privilege-speak, in line with how people in power today are trying to avoid being held accountable for their actions.

At the end of the day, “it seems at least possible that tweets are just tweets — that as difficult as criticism in the social media age may be to contend with at times, it bears no meaningful resemblance to genocides, ex-communications, executions, assassinations, political imprisonments, and official bans past,” Osita Nwanevu writes in The New Republic. “Perhaps we should choose instead to understand cancel culture as something much more mundane: ordinary public disfavor voiced by ordinary people across new platforms.”

In these trying times, however, it’s important to listen and learn from others’ experiences, and try to be on the right side of this power struggle — even if it begins and ends on a godforsaken social media platform.

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

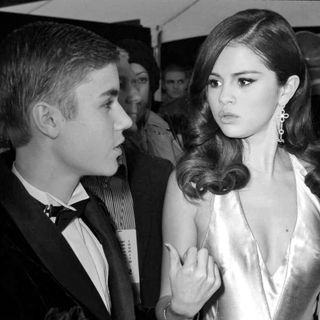

The Buzz Cut: Selena Gomez Says She Was ‘Emotionally Abused’ By Justin Bieber