Casteism Still Thrives in Elite Schools in India. What Would Anti‑Caste Education Look Like?

Anti-caste pedagogy would respect the agency and experience of all students, promote non-hierarchical relationships, and question how knowledge is transacted.

In a recent viral clip, an alumnus of PSBB — an elite, notoriously Brahminical school in Chennai — was seen talking about how certain castes are “naturally” able to do certain things: Kshatriyas can fight, Brahmins can read and preach.

Recent social media testimonies have affirmed the school’s adherence to such a stratified value system. But the incident speaks to an issue that extends beyond PSBB: Elite educational institutes in India are inherently casteist spaces, where discrimination is taught in as well as outside of textbooks. These institutes — considered the standard of “good” education in the country — thus work to perpetuate casteist stratifications of children based on false ideas of “merit” and inherent “ability.”

For Creya, who studied in a similar private school in Chennai, caste-bound notions of merit meant having her Dalit identity outed by privileged-caste teachers, fuelling casteist abuse from classmates.

Equality of opportunity is built into the Right To Education Act. But its implementation, particularly in private schools, is far from benevolent. “The school system privileges some children’s citizenship over the others — marginalized children are meant to be happy that they’ve gained access to these elite spaces and it stops at that,” explains Sarada Balagopalan, Ph.D., a professor of childhood studies from Rutgers University. And although schools are mandated to provide 25% reservations for children from economically or socially marginalized backgrounds, they rarely follow through.

Education can — and ought — to be liberatory. But “the language of merit, ability, and hard work are used to explain who deserves access, who succeeds and who fails — but these are notions shaped by class, gender, and caste in India,” notes Nisha Thapliyal, Ph.D., a scholar and practitioner of critical pedagogy at the University of Newcastle in Australia.

This myth of merit meant that Creya was met with expectations of failure. “I had a teacher who would constantly tell me that I will fail my exams and that I’m hopeless,” she shares.

Kumarjeet, on the other hand, represented the “exception.” In another Kolkata school, his teachers discouraged him from disclosing his Scheduled Caste certificate since he was “smart” — “they essentially didn’t see reservations as affirmative action but as a means to get admission for those ‘less smart,’” he says.

Elite schools thus fulfill their legal obligations in a way that disguises marginal inclusion as charity of sorts, rather than a matter of rights.

Moreover, such mindsets have damaging implications for children’s socialization. Shivani Nag, Ph.D., an expert in critical pedagogy and social psychology from Ambedkar University, Delhi, notes that in a homogenous environment, people are more likely to hold more rigid, unchanging views of “outgroup” members, leading to harmful stereotypes about inherent ability “othering” children who are caste minorities in these schools. How teachers — and, subsequently, peers — treat them is mediated by an “upper caste gaze,” Nag says.

However, as centers of learning, schools are as much about what they don’t formally teach, as what they do.

Related on The Swaddle:

There Is No Such Thing as Achievement Through Pure Merit

Bhavani, who was a Dalit student in a private school in Hyderabad was convinced for two years by her teachers that turning vegetarian would improve her Sanskrit. The vegetarian norm is true of many private schools in big cities — children face social sanctions if the food they take to school contains meat. N.S.*, who attended a school in Trivandrum, said that he was made to feel “like a criminal” for bringing meat to school. “I had a doctor’s prescription that needed me to eat eggs but they confiscated and threw it away,” he said — one teacher even called him an Islamophobic slur.

The benign ascription of culture to these Sanskritized ideals — food, symbolism, selective punishment based on “brightness,” and others — mask how Brahminism is the aspirational culture. Privileged children can thus wear their castes on their sleeve — sometimes literally, donning caste markers — while others feel compelled to hide their identities to assimilate.

“I realized people noticed which caste you were from. It was not a matter of pride for me because you stand out if you are from a lower caste among upper caste people… I felt insecure and tried to hide it,” says Ram, who identifies as Bahujan and studied in Chennai. There were holidays for Brahmin traditions, almost like the school was “meant for Brahmins.”

Brahmin children also represent the locus of aspiration and status, and teachers end up treating them with a very different yardstick. “Less privileged kids were given corporal punishment and beaten… I was never hit, even if my transgressions were the same,” says SM*, who is a Brahmin and studied in a private school in Hyderabad. Others testify that Brahmin teachers would also favor Brahmin children for cultural fests and activities.

In S.R.*’s school in Mumbai, a large idol of Saraswathi greets students at the entrance. This seemingly innocuous image quickly turns chilling when juxtaposed with anti-caste philosopher Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd’s childhood nightmares about the same ‘Brahmin’ goddess: “Saraswathi would kill our children if they are sent to school,” he recalled his aunt saying. Shepherd has since written extensively about Shudras’ and Dalits’ deprivation of education, which allowed Brahminical tradition to establish its hegemony and gatekeep schools.

All of these constitute schools’ “hidden curriculum” — how certain ideas and practices are understood as the norm. “Schools act as catalysts in the social reproduction of power and privilege,” writes Yuvraj Singh, a sociology of education scholar.

But caste seeps into the formal curriculum too, which is taught by privileged-caste teachers through the lens of their selective experiences. Experts note that children who cannot relate to these experiences find it more difficult to learn and thus internalize a notion of failure — that the problem lies with them.

Further, caste is reductively taught as a system of four “varnas” (without explaining who falls outside this system) — and as something that existed either in the past or in far-flung rural contexts — irrelevant, in other words, to children in elite spaces. The lack of flexibility to question the syllabus makes it harder to ask questions about caste. Creya, for instance, grew up with a different history because of how land reforms during colonial rule uplifted her community. But her school’s history syllabus, which uncritically reproduced nationalist discourses without any mention of caste, did not reflect this experience.

This silence serves to create a “smokescreen of equality, while denying the reality of oppression,” Nag observes. As a result, many children don’t have the vocabulary or the tools to identify and name their marginalization, leading to self-blame for unfair academic practices originating from caste discrimination.

Much of the casteism in elite schools is also administrative. “Anyone who was unable to pay the absurdly high quarterly fee was asked about their caste and their father’s occupation,” says Nikhil, who studied in New Delhi.

Here, like in several “big-city” elite schools, the usage of caste slurs was common — as was resentment among caste-privileged children against reservations in higher education while students geared up for college admissions.

For most students in such schools, caste only existed in conversations about reservation — and “we all know what caste-privileged people think about reservations,” Ram remarks.

Privileged children in these schools, therefore, end up internalizing casteism inbuilt in the pedagogy. They also mistake the absence of caste in their conversations as the absence of caste itself. But for children from marginalized castes, their “otherness” was apparent to them in ways they couldn’t put words to — they just knew they were different. Their teachers and inadvertently, their peers, made sure of it.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Indian Education System Reinforces Caste, Class Differences

Blueprints for an anti-caste pedagogy exist, on the micro and macro levels. Savitribai Phule, who was the first Bahujan and woman teacher in India, practiced an education model that was participatory rather than the traditional one-way sermon that is typical of Indian educational practice. Politician and thinker B.R Ambedkar’s philosophy of education was rooted in autonomy, was argumentative, and against the examination system, which he thought reproduced caste inequalities. Jyotirao Phule demonstrated the intertwining nature of Brahminical policy and pedagogy, and called for more plurality in education. Periyar was a strong proponent of inclusive education rooted in self-respect for all castes and women. All of them engaged with “how power works through the production, distribution, and consumption of knowledge,” writes noted sociologist Sharmila Rege. ”These ideas were, however, sidelined in favor of nationalist ideas of education as exclusive and competitive.

Increasing privatization today further ensconces education for the elites and sorts children based on casteist notions of inherent ability. National policies preserving the public-private divide and depoliticizing education into merely a rung in the ladder towards job markets stand in the way of education becoming something more. Further, rising nationalism and bigotry are seeping into curriculums everywhere, and schools advance these ideas unquestioningly.

On the micro-level, therefore, an anti-caste pedagogy would need to teach anti-caste movements, do away with degrading punishment, allow more listening and critique in classrooms, and accommodate diverse realities, among many other things. In other words, it must respect the agency and experience of students, promote non-hierarchical relationships, and question how knowledge is transacted.

“We must also look critically at the idea of respect,” says Shivani Nag. As of now, respect is often unquestioning in nature, cementing a repressive power dynamic between teacher and student without allowing much questioning or learning outside its confines. Instead, respect must be based on respect for human dignity rather than on arbitrary notions of seniority and wisdom.

On the macro-level, it may require a fundamental restructuring of the model of education that schools are built on.

More than being democratizing, mass education systems have served as “instruments of depoliticization,” Nisha Thapliyal notes. “Education must be fundamentally political work because we have to name and analyze power, inequality, and injustice to unlearn supremacist and oppressive ways of thinking and acting,” she observes, drawing on the concept of critical pedagogy — an egalitarian framework developed by Brazilian activist and educator Paulo Freire.

Further, undoing the idea of merit as a “random consequence of individual ability,” and teachers and administrators interrogating their own social positions are starting points for a non-tokenistic anti-caste pedagogy. “An anti-casteist pedagogy would… understand school spaces as constitutive dimensions of it [brahminism]. Rather than just our individual biases, the origins of the school system itself are so inherently brahminical. That has to be the shift,” concludes Sarada Balagopalan.

While anti-caste reformers made efforts to use education as a vehicle of social change, India’s education system turned away from this. As prominent educationist Krishna Kumar notes: education creates “the possibilities of change in social relationships,” but also, it “permits society to reproduce itself.”

Ultimately, we have a choice in defining what education means to us. Transforming it into a system of social change would mean that we take all forms of oppression — casteism, patriarchy, heteronormativity — seriously as structural barriers to a free and egalitarian society for future generations. It would also mean seriously evaluating the purpose that privatized education serves. This requires a fundamental rethink of education itself.

But, as Savitribai Phule reminds us: “We shall overcome and success will be ours in the future. The future belongs to us.”

*Names changed to protect anonymity.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

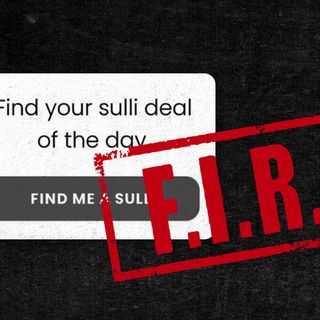

Delhi Police Files FIR Against ‘Sulli Deals’ App After Outrage From Muslim Women