Cellulite Is a Lie

An in-depth report explores the marketing gimmick that convinced women their skin was in need of curing.

We just stumbled up on an amazing piece, published in May on Refinery29, exposing an important but little known truth: cellulite isn’t a thing.

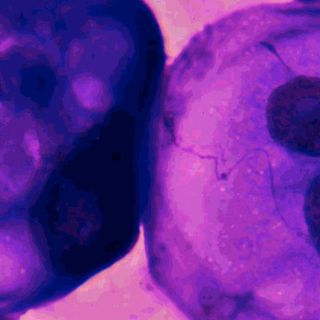

The author of the piece largely follows the arc of researcher Rossella Ghigi’s (the world’s foremost expert on the topic) work on the history of cellulite. Ghigi’s work traces how the medical term “cellulite,” which was originally used to describe cells in a state of infection or inflammation, and cellulitis, which was used to refer to pelvic infections — somehow made the jump into pop culture, and onto women’s upper thighs, framed as a condition that needed to be cured.

The modern history of cellulite — and the industry that sprung up around treating it — was heavily shaped by a variety of social and cultural forces that all coalesced after World War I. On the one hand, medical science was advancing at a steady clip from the end of the 19th century through the middle of the 20th, providing perhaps a backdrop for the medicalization of terms, and societal comfort with spending on cures and treatments. At the same time, Paris became the centerpoint of a burgeoning beauty industry that flourished because of women’s newfound liberation and independence in postwar Europe.

Now this is where things get interesting. The author of the Refinery29 article, Kelsey Miller, posits that the coining of the term cellulite was a patriarchal reaction to the increasing visibility and presence of women, on the streets, in workplaces, anywhere outside their homes. Paradoxically, women’s empowerment, in the form of fashion, financial independence, and visibility, presented a unique opportunity to profit off of a nonexistent malady that would keep women spending endlessly while they remained crippled with insecurity.

There is a lot more to unpack in this great read, especially the parts about how dimpled skin was celebrated as a natural and beautiful part of human skin throughout art history up until the mid twentieth century. In fact, no one, from medical experts to artists to average women, thought that dimpled skin was a problem that needed to be addressed until an industry arose out of its elimination. There’s also a great exploration of how fat phobia emerged at this same cultural moment when women’s bodies — and exerting control over them — became a dominant narrative in Western culture.

But the most fascinating part of this story is how normal skin, and the dimpled appearance of fat cells under the skin that occurs in approximately 90% of women, became something that we obsess about and feel bad about. Along with skin whitening creams, vaginal douches, and countless other meaningless products, women are spending money to address problems that literally don’t exist. These products are at best falsely advertised as treatments (for conditions that aren’t conditions), and at worst, they are actually harmful to our health. As the purchasers of these products, we have to stop and ask ourselves: who stands to gain from our — literally and figuratively — buying into these marketing ploys? Because it’s certainly not us.

Related

GoI Underestimates Breast Cancer Incidence, Report Finds