Cinema May Be Losing Its Stars. But Is That a Bad Thing?

Cultural commentators both in Bollywood and the West are lamenting the death of superstardom. But it also signals the fall of patriarchal stardom.

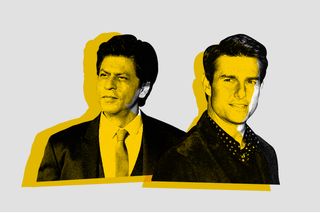

An eight-year-old clip of Shah Rukh Khan has been doing the rounds on Instagram and other social media platforms lately. In it, the actor quips that he is “the last of the stars.” In the last few years, cultural commentators around Bollywood have often hinted at us witnessing the beginning of the end of stardom. Multiple trends point to this happening. The biggest of them is that movies helmed by established big-budget actors are no longer the sure-shot crowd puller they used to be.

Bollywood isn’t the only cinematic establishment in the world that is facing a stardom crisis. On 1st December, film critic Wesley Morris of the New York Times wrote a long piece lamenting the death of the movie star system in Hollywood. Morris takes the example of Top Gun: Maverick to comment on how the film is fuelled entirely by Tom Cruise’s superstardom and public persona, noting that it has become an increasing rarity. Fewer and fewer films in Hollywood today are carried entirely on the shoulders of one (or more) towering actor and their charisma. Movie stars are no longer the most bankable business strategy for Hollywood, and that signals the end of an era. However, while a section of moviegoers and commentators remain nostalgically attached to the star system, the end of stardom may not be a bad thing entirely.

In Bollywood, and in several other film industries of India, star-powered films have often featured and celebrated unrealistic, larger-than-life stories. From a purely artistic standpoint, star vehicles have often rehashed the same story multiple times with minor tweaks here and there. In fact, stars like Salman Khan and Rajinikanth (much like Tom Cruise and Clint Eastwood) achieved much of their stature by playing a version of the same character in every movie, leaving very little space for exploring out-of-the-box themes and narratives. The end of stardom, then, could potentially also trigger a shift in these narratives. As audiences are exposed to cinema around the world with the help of the internet and express their dismay at repetitive performances, their rejection of stars could force actors to reinvent artistically.

Politically, too, star movies have often featured questionable values and ethics. In India, for instance, these films have often uncritically celebrated patriarchal institutions such as the family, and have had the tendency of glorifying physical violence and masculinity. They peddle toxic notions of love and affection. From Amitabh Bachchan’s Angry Young Man to Salman Khan’s on-screen version of Salman Khan, the template of a macho action hero has often remained the most identifiable aspect of an Indian superstar film. The end of stardom, then, may also force erstwhile superstars to realign their artistic choices with the changing political scenario. This may have arguably led to a superstar like Amitabh Bachchan, helming an anti-caste film like Jhund.

Related on The Swaddle:

Bollywood Needs Heroes Who Don’t Self‑Destruct When They’re in Love

This, of course, is not to disregard the importance of entertainment in the cinematic (and other artistic) medium. It is indeed understandable, perhaps even desirable, that art — often consumed by people for their leisure — retains its entertaining value. As film critic Anupama Chopra writes, “Great films like great literature construct an elaborate lie to lead us to the truth. They widen our perspective and give us new ways to see the world. But sometimes, all we want is a diversion.” There is no denying that an activity people engage in to loosen themselves up must be entertaining, and star power gives us that. However, the defense of entertainment has thus far upheld a singular, masculine, and patriarchal institution of stardom.

However, the end of stardom may not automatically lead to progressive cinema. In Hollywood, for instance, as Morris writes, the place of stars has been taken by “intellectual properties.” Superheroes and franchise characters — instead of actors — have become the new stars in modern-day Hollywood, pushing the industry into an age of mechanical, formulaic, and predictable filmmaking. Artistically, there hasn’t been much change from the monotony of star-powered films to superhero and franchise films. In Bollywood, on the other hand, the twilight years of the star system has witnessed the growth of a new kind of cinema, and new kinds of actors to helm it.

In the last few years, content-driven cinema — films critiquing and commenting on socio-political topics — has become the new buzzword in Bollywood. Helmed by actors such as Ayushman Khurana, Rajkummar Rao, Tapsee Pannu, and Radhika Apte, these movies are less larger-than-life than star movies, and often attempt to deliver some sort of social and political message. However, in recent times, critics have noted that “content-driven” cinema is often lacking in the artistic commitment of storytelling that is essential in moviemaking. Further, recent examples of social “content-driven” cinema has often been found to be lacking in nuance and research of the very topic it attempts to unravel. For instance, Ayushman Khurana’s film Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui, a film with a trans woman protagonist, featured a cis woman playing the role.

Still, the end of stardom may yet be a good thing. It stands to democratize cinema by deflating the importance of the lead actor. It can lead to more equitable payments on a film set, and a more grounded treatment for actors. In a recent interview, actor Jahnvi Kapoor noted, “I remember papa telling me stories about how Rajesh Khanna’s car would drive away and women would take the sand and put it in their maang. I don’t think they would do that for anyone today.” The end of stardom could lead to actors being treated as professional workers — instead of being deified as gods.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

Woe Is Me! “I Live In Constant Fear Of Being Fired. How Do I Cope?”