A “hygiene hypothesis” has perturbed scientists with its claims about childhood immunity. The theory is early exposure to certain microbes helps in the development of a strong immune system. But new research shows that good hygiene practices, such as washing hands and regularly cleaning home surfaces, are also necessary for a strong immune system.

Researchers reviewed previously published studies to assess levels of microbial exposure in different home settings. There is an “apparent conflict between the need for cleaning and hygiene to keep us free of pathogens, and the need for microbial inputs to set up our immune and metabolic systems,” the researchers noted.

The study, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, suggests the relationship between hygiene in clean homes with immune systems, with scientists noting we can’t be “too clean for our good.” The practices that prevent infections should thus be balanced with microbe exposure which strengthens the immune system.

This is because the microbes found in a typical modern home don’t necessarily aid the immune system. While exposure to microbes is important for immunity, the exposure required does not come from a household atmosphere. Hygiene practices such as handwashing and surface cleaning are, therefore, beneficial in preventing infections that can make us sick, rather than compromising our immunity.

It is instead the microorganisms of the “natural green environment” that are beneficial for our health. “Exposure to our mothers, family members, the natural environment, and vaccines can provide all the microbial inputs that we need,” Graham Rook, a professor of medical microbiology at University College London, lead author of the study, said. In other words, we get most of the microbe exposure we need from other sources.

Related on The Swaddle:

Research Is Revealing How the Immune System Responds To Viruses Differently in Men, Women

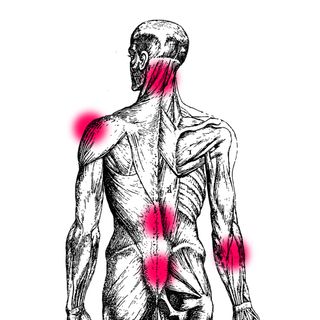

In the current review, the researchers highlighted the need to maintain good hygiene at home. They identified nine “key risk moments” that carry risks of gastrointestinal disease and respiratory tract infections — such as food handling, toilet usage, caring for domestic animals, caring for infected family members, touching frequently touched surfaces, and so on. During these moments, hands, cleaning equipment, clothes, baths, and many more surfaces are involved in the spread of infection.

Moreover, the findings will also help differentiate between “targeted” and “non-targeted” hygiene practices. By “targeting” hygiene practices in these areas and contexts, we could achieve a balance between preventing infections and also achieving the necessary microbe exposure. “Targeting hygiene practices at key risk moments and sites can maximize protection against infection while minimizing any impact on essential microbial exposures,” the paper stated.

But “non-targeted” cleaning practices — such as disinfecting floors or “deep cleaning or fogging” of areas — on the assumption that it protects against infections can actually increase chances of adverse effects on the immune system. This is because crawling infants and children can get exposed to harmful cleaning agents.

The study is relevant against the backdrop of the Covid19 pandemic response. Ostentatious deep cleaning measures such as “hygiene theaters,” the practice where people “scrub their way to a false sense of security,” as Derek Thompson noted in The Atlantic, are less effective than targeted measures such as social distancing, access to hand sanitizers, and so on. The illusion of improved safety while doing little to actually reduce any risk differentiates the notion of “cleanliness” from “hygiene.”

The researchers stressed the need to prevent scientific literature endorsing the idea that hygiene practices are associated with “increases in immunoregulatory disorders.” “We must discourage suggestions in the media or published articles that we should relax hygiene standards and ensure that such statements are replaced by instructions for intelligent use of targeted hygiene,” the paper cautions.

Guided by “evolutionary and historical knowledge,” it is possible to narrow down which microbe exposures are indeed essential to our physiology, the study concluded.