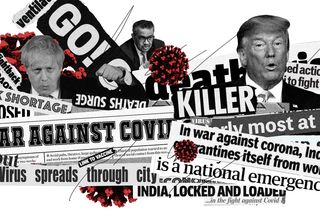

Describing the Pandemic As a ‘War’ Is Ineffective and Dangerous

Using the lexicon of violence to describe the pandemic normalizes the suffering of the vulnerable, and allows governments to act without accountability.

India’s official hashtag in response to Covid19 is #IndiaFightsCorona. Words such as ‘battle,’ ‘war,’ ‘fight,’ ‘kill,’ and ‘warrior’ are repeatedly used by the state and media to describe the pandemic. Our fixation with describing pandemics and illnesses using an overly militarized tone is not new. We’ve had the ‘War on Cancer,’ ‘Ebola Wars,’ and ‘Battles with Jaundice.’ However, this excessive use of violence as a metaphor for describing a contagious pandemic like Covid19 can be dangerous, divisive, and at times, fatal.

When the pandemic is framed as a war, the government places itself in the role of an unaccountable military general that ‘calls the shots.’ Such unquestionable authority allows the government to divert its citizens’ attention from its failure to control the spread of the virus, and to foster a narrative that blames the patients. For instance, while recent research estimates that the virus entered India in 2019, pervasive media rhetoric berated Indians returning back home, and migrant laborers walking home after the lockdown was imposed in March 2020, as ‘super-spreaders.’ Moreover, while state and central governments played blame-game charades, prime time anchors vehemently dehumanized the sufferings of migrant labors who were walking thousands of miles barefoot.

One may argue that controlling a pandemic requires war-like preparedness, and the easiest way to communicate the severity of the disease to the public is to use war jargon. However, the war analogy has significant and dangerous pitfalls, as it normalizes the suffering of the vulnerable and demonizes the illness. By using the lexicon of violence in their public awareness campaigns, the state, as wartime government, presents itself as needing citizens’ unconditional support. This enables the government to define the contours of what we can question and what we cannot. For instance, while media reports and WhatsApp forwards incessantly questioned the deceased migrant laborers for sleeping on a railway track, there is eerie silence on why funds collected by the authorities to ‘fight’ the pandemic are not subject to public audit.

The war analogy can also strategically enable authorities to use excessive force against its own citizens, especially against those who refuse to unconditionally support the government’s decisions or those who question the authorities for their inaction. Since the Covid19 outbreak in India, media houses have allegedly been advised by the authorities to publish positive stories; simultaneously, journalists who highlighted regulatory gaps in supplying basic amenities to healthcare workers and support to the economically vulnerable were slapped with provisions under the Disaster Management Act, 2005 and/or the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.

At the community level, the war analogy and its lexicon of violence are used to normalize human rights violations for the greater good. And when these violations are inflicted upon the vulnerable, minorities, and immigrants, their acceptance depends on the pretext that desperate times call for desperate measures. For instance, when the spread of Covid19 was accelerating at an alarming rate in the U.S., the self-proclaimed wartime president, Donald Trump, gave a face to the invisible enemy – China. This War against Coronavirus enabled Trump to implement stricter immigration rules and moratoriums against foreign students (now rescinded). In India, when the virus was spreading at an alarming rate, the lexicon of violence triggered masses to equate the ‘invisible enemy’ to people belonging to the north-east of the country. Further, in pursuit of making the ‘invisible’ visible, prime-time news anchors weaponized the infamous Tablighi Jamat incident to incite religious sentiment.

Related on The Swaddle:

Waiting for a Vaccine Cannot Be Our Pandemic Response Strategy

While war calls for belligerence, mobilization, force, and ‘call of duty’ – all things that involve leaving one’s home – this pandemic requires staying at home, refrainment, and levels of hygiene that are the antithetical to the perceived masculinity of war. This leads to hyper-masculine leaders refraining from wearing masks and mocking people not participating in economic activities during the pandemic.

Further, while war is often territorial and requires citizens to identify with nationalistic (or patriotic) agendas, Covid19 is a global issue. Infusing nationalism in pandemic-related discourse is merely a diversion from core issues, such as underfunded health infrastructures, deteriorating scientific temperament in illiberal democracies, economic inequalities, and religious intolerances.

Such politicized communication also takes attention away from uncomfortable but relevant scientific findings, such as the relationship between Covid19 and climate change, and how weakened environmental regulations will lead to similar pandemics in the future. All these findings challenge how the current power structures in society reinforce corporate-political lobbies’ monopoly over natural resources, which ultimately leads to concentration of wealth among a few, in turn giving them access to better health care in such crises. Therefore, by evoking the fear of war and making the invisible enemy visible, the use of the lexicon of violence itself becomes an act of violence, digging the landless and economically vulnerable deeper into poverty and social exclusion.

Violence in war is considered a route to freedom, a means to an end, which is not true for pandemics. War is perceived as winnable, which is also not true for pandemics – we do not win against viruses; we adapt and evolve as a cosmopolitan society through scientific advancements. War solutions are directed from the top, while pandemics are controlled through localized community action. Doctors and health professionals are not warriors and their deaths should not be seen as martyrdom. Instead, they are highly skilled professionals who would any day exchange a glorified death in an imaginary war for timely salaries and safety equipment.

This brings us to one of the most pertinent linguistic questions of today – if not through the lexicon of violence, how can we effectively communicate the severity of a pandemic to the masses? The answer lies in the ‘lexicon of empathy.’

Although metaphors cannot communicate scientifically, our choice could have been better. Covid19 could have been a ‘journey’ that we all need to take together. Healing from it could be seen as a ‘river’ that needs strategy, passage of time, community support, boundaries, and reportage of over-flow. For instance, New Zealand, one of the first countries to successfully control the spread of the virus, refrained from using the lexicon of violence. Rather, the focus was on empathy, with messaging such as ‘Be Kind,’ ‘Stay Home Save Lives,’ and ‘Support Your Community.’ Awareness campaigns that do not masculinize the message – simply, ‘Wear a Mask,’ ‘Do Not Step Outside,’ and ‘Wash Your Hands’ – can be effective by themselves.

Even if one went down the path of portraying Covid19 as the enemy, our response could have been ‘#IndiaUnitedAgainstCorona’ (both literally and figuratively). But instead, we chose to fight – against the virus and among ourselves.

Shashikant Yadav is an energy and water policy researcher currently affiliated with the Central European University, Vienna. He writes about environmental justice, ecocide law, and illiberal democracy.

Related

Scientists Design Reusable N‑95 Mask Prototype in Effort to Ensure Safety, Sustainability