Do Parents Have The Right to Choose Circumcision, Ear Piercing for Babies?

These painful, yet culturally acceptable, practices fall in a gray area.

A year ago, a mother in the US posted to Facebook a photo of her baby — with a dimple piercing.

So I got the baby girl's dimple pierced!! 😲😲😍😍💗💗It looks so cute, right?!! I just know she's gonna love it!! She'll…

Within days, the post had thousands of shares. And Enedina Vance was getting hate mail, social media backlash, and threats to report her to Child Protective Services. The photo — which had been photoshopped — had accomplished what Vance set out to do: Start a conversation about babies’ bodily integrity.

“The reaction that parents have when they see this beautiful perfect baby being … mutilated, that initial shock, that reaction of anger, I want them to hold on to that,” Vance told CNN at the time.

—

Body modification of babies and young children has a long, global history. In the Andes of South America, during the 12th through 15th centuries, cranial shaping was a marker of identity; infants’ heads would be bound to shape the growing skull either wider and squatter, or longer and narrower (the latter eventually became the standard of practice and possibly beauty at the time). In China, breaking and binding the feet of very young girls originated in the 10th century and persisted well into the 20th. Many places in between have had their own versions of such modification of young children’s bodies. Female circumcision — also known as female genital mutilation or FGM, a practice most prevalent in the Horn of Africa, West Africa and in some North African countries, but also alive and thriving in pockets of India — is on its way out as global campaigns and court petitions gain traction.

Still, two forms of accepted infant body modification persist in India and elsewhere — the very two Vance, an anti-circumcision and anti-piercing activist, was hoping to draw attention to in the US: male circumcision, prevalent among slightly less than 20% of India’s male population, and ear and nose piercing, ubiquitous among India’s female population. The question is: Why?

“No one has the right to alter, modify, or mutilate another human being’s body for aesthetic purposes, not even parents,” Vance said last year.

That argument is difficult to disagree with, but it doesn’t quite strike at the main thing propping up these practices — a thorny knot of parents’ religious beliefs and health myths.

We’re not here to argue religion, though it is worth noting, the religious beliefs of parents aren’t necessarily the religious beliefs of a grown child. Ear and nose piercing has its roots in the Hindu rite of karnavedha or karnavedham, while male circumcision is a facet of Judeo-Christian and Muslim traditions; to be katwa in India is as much a statement of penile status as it is a slur-laden calling card for certain communities.

Perhaps because of this, there have been tentative efforts, in recent years, to normalize the circumcised penis broadly among Indian society. In this, advocates are assisted in highly questionable, allopathic research from the US, where male circumcision in infancy is the norm, that links circumcision to lower rates of HIV and less risk of urinary tract infections.

However, as Martin Robbins writes in The Guardian, “The hygiene argument is self-evidently daft – for no other part of the body do we advocate ‘chop it off’ over ‘wash it more thoroughly’ as the preferred option for improving hygiene.”

The practice also comes with serious side effects that, critics argue, rival the consequences of FGM, yet somehow enjoy acceptance: less sensitivity and pleasure during sex, and potential psychological fallout.

Ear and nose piercing may come with less-serious ripples — infection is a risk, especially for babies who haven’t completed a full immunization schedule, but the function of an earlobe is less altered by piercing than the function of a penis by removing the foreskin — but it’s no less a conundrum. Like male circumcision, ear and nose piercing cause pain and are typically done in infancy (in part, reasoning goes, because babies won’t have a memory of said pain, as would an older child). Also like male circumcision, its religious roots have been compounded by claims of completely unproven health benefits, in this case from Ayurveda, to add weight against any waverers.

—

Both practices, male circumcision and ear/nose piercing, have evolved, among wealthier, urban, educated populations, to be more ‘cultural’ than mandatory; baby ear/nose piercing has even become a statement of socioeconomic class. Like skull binding in the Andes hundreds of years ago, these are ways in which we ascribe identity to blank slates, offer babies protection and welcome them into a fold.

But unlike that era, the 21st century is full of conversations around bodily autonomy, consent and respect that challenge the bonds of tradition. Parents may or may not have a right to choose these body modifications for their children before children are old enough to have a say; in a communal culture like India, where family as a whole takes precedence over the individual, there is an argument to be made that such decisions aren’t a violation, but a validation of a child’s place within a family and community. But as we’re choosing, it’s important to acknowledge: Any choice in favor of these rituals for a child too young to reason has less to do with our child and their life, than it does with ours.

Related

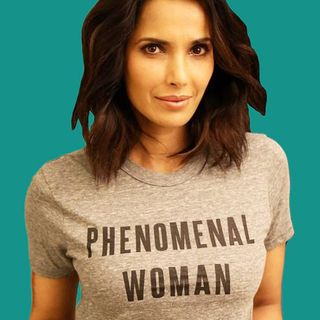

Controversial Crush: Padma Lakshmi