Donors, Couples at Mercy of India’s Unregulated Egg Donation Industry

Egg donors aren’t told the risks, and couples aren’t told the odds.

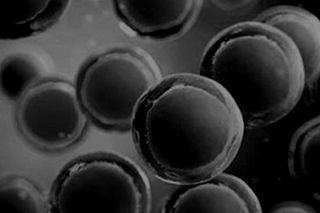

The fertility industry in India is a booming one today. IVF alone is a Rs. 1,078 crore market, projected to reach Rs. 2,600 crore by 2022. You may have undergone fertility assistance; you probably at least know someone who has. But IVF requires raw material that many couples struggling with infertility can’t provide: a healthy egg. Two out of 10 infertile couples require donor eggs, per a Scroll report examining the vast, unregulated industry that supplies these eggs.

In a nutshell, the industry takes eggs from a fertile woman, who undergoes a battery of hormone injections to stimulate egg production beyond the usual one to two a month; these eggs are then surgically removed and sold via a network of middlemen and fertility centres to couples struggling with fertility.

However, donating eggs comes with serious risks and side effects — too many hormones in the system can lead to over-stimulated, painfully swollen ovaries, weight gain, abdominal pain and nausea. In more rare cases, it may lead to fluid buildup in the abdomen or lungs, kidney failure or even stroke. Furthermore, studies have suggested, though have yet to confirm, that hormonal treatments can contribute to certain cancers.

But most donors are not informed of the health repercussions. In fact, most egg donors interviewed by Scroll were unaware of any negative health effects associated with their regimen, though two of the five interviewed had experienced health complications.

Egg donors tend to be poor women who find they can earn more by donating eggs than by the more traditional employment available to them. Some are desperate for the security money can buy; one woman interviewed by Scroll turned to egg donation in order to provide for her son after leaving an abusive husband, another was the steadiest source of income for her family. Egg donors can get paid anything between Rs. 20,000 to a few lakhs, depending on a number of factors — a higher level of education, a fair or dark complexion (depending on the region), and attractive features are all characteristics couples will pay donors more for.

This experience is generally hidden from the other side of the business — comparatively affluent couples who have difficulty conceiving. These couples feel social pressure to opt for IVF, due to a “cultural perception in India that equates fertility with a successful marriage,” the article explains. Unfortunately, there is a misconception that if they go for conceiving via IVF and using donor eggs, they will instantly get a baby within nine months, Rakhi Ghoshal, a working editor of the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, told Scroll. Many couples are ill-informed and unaware of the success rates of IVF pregnancy, and end up experiencing emotional and financial distress.

The result is a landscape where every player is out for themselves. “I have had cases where an egg donor took the injections from me and got her eggs retrieved at a clinic which paid her more,” one doctor told Scroll on condition of anonymity. “Once I had a surrogate who got pregnant and later underwent an abortion as another clinic was paying her more to be a surrogate.”

And in the absence of laws, guidelines get flouted. While Indian Council for Medical Research guidelines nix meetings between couples and donors, some couples will pay extra to be able to weigh in person the genes that will help create their child. Agencies and clinics are the facilitators. “For couples who are ready to pay and insist on a very educated, good looking donor, we have arranged flight attendants, lawyers,” said the head of one agency that supplies donors and surrogates.

India is not the only country with an ethical dilemma around egg donation and egg selling; the problem is a global one that has been much debated. While some decry the commercialization of human body parts as a slippery slope, others argue that the industry empowers individuals by putting choice and control over their bodies and incomes squarely in their hands.

But in the absence of any concrete laws in place, the odds that profit goes hand in hand with exploitation, inadvertent or intentional, increase. The Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill, which would go a long way toward encouraging transparency and protecting egg donors, has been drafted, but there is no clear timeline for when the Bill will be considered or ruled on.

Related

Skin‑To‑Skin Contact After Birth Has Big Benefits, But Only If Skin Is Clean