In the 1960s, researchers unearthed 61 skeletons in the Nile Valley region as the first evidence of warfare between humans. The deaths were then thought to be the result of a one-off armed conflict. But a recent reexamination of the 13,000-year-old remains shows that people died over several years due to recurrent violence that was exacerbated because of climatic changes during the period.

Published in Scientific Reports, the findings build on previous research around remains discovered in Jebel Sahaba, a prehistoric cemetery that dates to between 13,400 and 18,600 years ago, marking the oldest recorded evidence of interpersonal violence among human groups. The study reframes the conflict between hunter-gatherers in the context of climate change and offers a unique lens into the emergence of violence and mass death in the stone age.

A closer examinationof the skeletons — of adults, teens, and children — revealed previously undocumented healed and unhealed injuries sustained from brutal and continued violence. “That injury pattern more likely arose from periodic, indiscriminate raids rather than a single battle, in which the dead would have consisted mainly of male fighters,” the researchers say.

This suggests violence was a material part of life and resulted from multiple raids and ambushes — or “minor battles” — during that time because of resource competition, researchers from the U.K. and France say. And more importantly, “repeated violent episodes [around that time] were probably triggered by well-recorded environmental changes,” paleoanthropologist Isabelle Crevecoeur, who conducted the study with her colleagues, told ScienceNews.

Since this was a pre-agriculture period, rival groups living in the same space competed for meals and other resources, which might have triggered fighting among regional groups. “The new report fits a scenario in which ancient, possibly culturally distinct communities violently raided each other when dwindling resources threatened their survival,” said bioarchaeologist Christopher Stojanowski of Arizona State University in Tempe, who did not participate in the new study but has studied the Jebel Sahaba remains.

Related on The Swaddle:

Climate Change Could End Human Civilization by 2050

The Nile Valley, the area between now southern Egypt and northern Sudan, was believed to be a space of refuge for prehistoric people, who might have moved there from the arid, less fertile areas in Africa and southwest Asia. Moreover, the expanse of plains also meant an easier search for animals to hunt and fish.

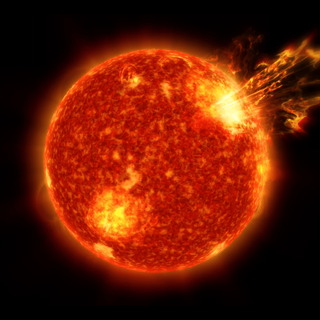

This time coincided with a fluctuating climate — between 11,000 and 20,000 years ago, the Ice Age showed signs of slowing down, resulting in widespread flooding and disrupting the ecological balance; Crevecoeur mentions there was proof of very extreme flooding of the Nile, which resulted in reduced fishing and hunting spots and depleted habitats.

The origins of warfare have been a matter of dispute for long: whether violence originated among Stone Age hunter-gatherers or among state societies within roughly the past 6,000 years. The new findings thus alter the history of violence in the stone age.

“These results enrich our understanding of the contexts in which violence emerges among foragers,” Luke Glowacki, at the Department of Human Biology at Harvard University, told NewScientist. “They provide additional evidence for an emerging consensus that foragers, just like agricultural peoples, had interpersonal violence in the form of raids and ambushes.”

The researchers note, however, that the cause for the violence cannot be determined with absolute certainty, since there are no written documents. But the consensus was drawn based on the fact that this earliest recorded violence was sporadic, long-drawn, and took place against the backdrop of climate change depleting resources needed for survival.

Records of hunter-gatherers from the stone age not only offer an insight into warfare, but also show how climate change — that manifests as resource scarcity, flooding, and loss of habitat — triggers conflict and displacement. “These changes were not gradual at all,” Isabelle Crevecoeur says. “They had to survive these changes that were brutal.”