Effectiveness of India’s Top‑Selling Diabetes Medications in Question

India’s top-selling medications for diabetes have been approved for sale based on shoddy testing, with the requisite trial data falling well short of international standards, finds a new study published in the jour...

India’s top-selling medications for diabetes have been approved for sale based on shoddy testing, with the requisite trial data falling well short of international standards, finds a new study published in the journal BMJ Global Health. As a result, the health of many patients with type 2 diabetes is potentially at risk, the researchers say.

India is often referred to as ‘the diabetes capital of the world,’ with 60 million of its population affected by type 2 disease. Two-thirds of all diabetes drugs sold in India are what is known as fixed-dose combinations, or FDCs for short, often containing metformin and one other drug. While metformin is the drug of choice for treating diabetes — designated as such by its place on India’s essential medicines list — the fixed-dose combination version is not recommended, as the rigid dose runs counter to the constant monitoring and adjustment of drug doses diabetics need to maintain adequate blood glucose control.

“We are concerned that growth in sales of FDCs for diabetes outstrip metformin,” says Dr Allyson Pollock, director of the Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University, and the study’s lead author. “Moreover, some of these FDCs have not been approved and some of those that have been do not have good clinical trials evidence underpinning them. We are concerned that some manufacturers are applying for licenses in the absence of approval and or in the absence of good evidence of safety and efficacy and that these medicines could be doing great harm.”

Five brands account for all FDC sales, by value and volume. While all five had been given the green light by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, three had already been sold and marketed even before they were submitted for regulatory approval. In fact, four these common FDCs were on the list of FDCs banned by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in March 2016 — a ban that was subsequently overturned by the Delhi High Court, a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in 2017, following extensive lobbying by the multinationals behind the manufacture of FDCs.

FDCs are often justified for the convenience of their static dosage, which some say improves patient compliance.

However, “the convenience of FDCs should not trump efficacy,” the researchers write.

And efficacy is in question. Scrutiny of the clinical trial data for these five FDCs revealed that not one provided any evidence of safety or effectiveness for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Researchers combed data on these FDCs from 25 published and unpublished trials with information from a commercial drugs sales database (PharmaTrac) for the 12 months from November 2011 to October 2012.

The trial data were reviewed in the context of the four WHO standards set for FDC approvals in 2005. (India has its own regulations for FDCs, but the WHO guidelines are more comprehensive and rigorous, researchers say.)

None of the 25 trials met all four WHO criteria. And 18 of them were sponsored by multinational corporations or conducted by pharmaceutical companies, prompting the researchers to question the independence of the approvals process.

Researchers are calling for CDSCO to go public with the data it used to approve these drugs, so people are made aware of the lack of evidence on their safety and effectiveness.

While Pollock says the best thing for doctors and patients to do is to follow the guidance of India’s essential medicines list, that alone can’t contain the problem.

“Potentially an awful lot of people are taking these medicines but we don’t know about the harms [these drugs are causing],” Pollock says. “There’s no proper follow-up because most of the medicines are being bought on the open market. We have the sales data but we don’t have a good way of tracking who’s taking these drugs and what is happening to patients.”

Which is why the authors are calling for broader reform of the overarching law, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, which pre-dates independence and has been tortuously and poorly amended in the years since.

“The rules governing clinical trials which underpin safety and efficacy of FDCs have been weakened and do not protect patients,” Pollock notes.

Related

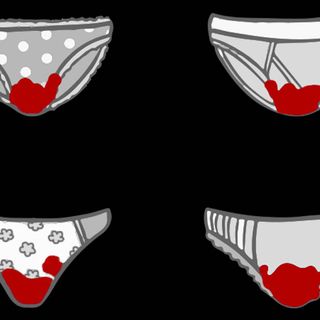

Researchers May Have Found the Cause of Heavy Periods