Employers May Favor People They See In Person. How Does This Impact Pandemic Work Culture?

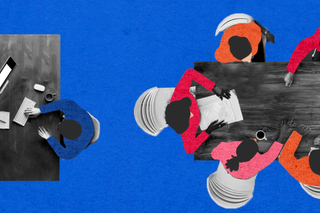

The current hybrid work culture raises urgent questions about how embedded “proximity bias” is in workspaces.

If there’s one truth that has remained unchanged during the pandemic, it is that work knows no bounds. The holy trifecta of mails, messages, and meetings continues undeterred whether it is a work-from-home setting or the office. Yet, human bias may have a glaring blind spot while ascertaining people’s productivity and performance.

This cognitive thinking is called “proximity bias.” Like all blind spots, employers and workers may unconsciously and unwittingly favor people closest to them and undervalue those in remote locations. “Proximity bias is the incorrect assumption that people will produce better work if they are physically present in the office and managers can see (and hear them) doing their jobs,” Fast Company noted.

This “accidental favoritism” segregates workers into two categories, those who are present physically and those who aren’t. The prevalence of the hybrid work culture raises urgent questions about how embedded proximity bias is in workspaces, and how best to address it.

Showing favor to people in physical proximity and perceiving them as better leaders are linked to our cognitive decision-making process. For generations, humans have opted to use mental shortcuts to prioritize what feels the safest — what we call “heuristics.” Think how people immediately flock to those they know well in a social setting or sit near those they know best. Or, as HRM puts it: “Who are you more likely to lend $100 to, your neighbor or that guy who lives four blocks away, assuming they have an equal need for the money?” This also means proximity bias is not a pandemic-triggered concern; it has always existed in overt and tacit ways in the professional setting.

“It’s human nature to confer preferential status to those in our immediate vicinity. When we say something or someone is ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ we’re activating the proximity bias,” Katica Roy, CEO of Pipeline Equity, noted in an article.

Irrespective of how “human” and “common” they are, blind spots can be deleterious. This unhealthy assumption leads to a view that people close to the employers or team leaders are more qualified and productive than those in remote settings. This has a domino effect: these “physically” present employees may get the chance to sit in more meetings, interact more with higher-level executives, get more opportunities as they appear “harder working” and more “trustworthy.” It becomes a matter of convenience to ask an in-person employee their opinion or hand them tasks rather than log into Slack to communicate with remote employees.

One need only take a peek at anecdotal evidence, along with studies, to debunk proximity bias. Research notes remote employees are just as productive, even more in some cases than their in-office counterparts.

Related on The Swaddle:

Work‑From‑Home Policies Are Popular in Theory, But Succeed Only in Ideal Settings

In a work setting, people end up making decisions based on their biases, instead of tangible data or knowledge. “You perceive your judgment to be logical, but because you’re using shortcuts, it might lead you to the wrong assumption,” reads an article in Raconteur. A 2015 study in China, for instance, found remote workers performed better than in-person workers; yet, they lost out to in-house staff when it came to performance-based promotions. This trend may be global. Almost 64% of managers erroneously believe office workers are higher performers than remote workers.

The notion of “employee presenteeism” has felt archaic for a while now. The specter of office has for long been witness to performative productivity; even people in offices may not be working or be mentally present.

Conversely, remote working has shown how people can be productive and constructive for mental health even while being physically absent. Removing the logistical barriers of conveyance has saved time; even marginalized groups who reported feeling insecure at the workplace can focus on performance and work at home. The set-up has particularly worked in favor of neurodivergent people; the distance from chatter and distractions makes the hybrid and work-from-home model rather ideal.

The awareness and discourse around proximity bias are not only related to productivity but intersectional gender justice. Experts note the hybrid work route will “complicate progress towards more diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces.” Preaching the new dawn of hybrid work doesn’t always translate into practice. Even though 82% of leaders endorse hybrid work settings, only 13% are concerned about reducing inequity between remote and in-office employees, according to a study.

From an employee’s perspective, the fear of missing out is quite tangible. Rebecca Corliss confesses to feeling a tangible fear of “phoning in” a meeting even if she was ill on that day. “The consequences of proximity bias echo louder than a sneeze,” she noted in Fast Company. Workers have struggled to find ways to get noticed and get their contributions recognized.

Work from home demands a rethink of professional space and time; the lines of what constitutes “proximity” are changing radically. This leaves employers to grapple with the question of how best to include and evaluate those working from home.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Do We Lose When We Don’t Inhabit Physical Spaces Like Offices, Universities?

This reckoning is needed in a post-pandemic culture. “I think it will become more pronounced when there will be, say, individuals coming into the office and they will start to create some kind of in-group, like ‘we are the office people,'” Ali Shalfrooshan, a UK-based occupational psychologist, told BBC Future. The lines may end up becoming more fraught; developing a culture where home-workers are treated as “second-class” or less worthy. This pattern may hamper feelings of belongingness and friendship in the workspace, both are tied to job satisfaction and productivity in the long run.

The first step to addressing a bias is to acknowledge it. “Out of sight, out of mind” is convenient; and convenience is where equity and innovation slip through the cracks. Identifying the bias and the systems that encourage it is a visible step of the ladder. “If the office reopens and executives are first in the office, and even if they say you have a choice whether or not to come in, it sends a very powerful signal that the choice you have now is between your family or your career…If you have two playing fields to administer, they are inequitable by design.” GitLab’s head of remote, Darren Murph, explained.

This involves a reframing of what classifies work and how is it classified. Then, perhaps, leaders and employers can reframe decision-making processes. This can involve having a diverse representation of viewpoints to make inclusive work policies. Even minor practices like ensuring all in-room conversations are transparent and can be heard by remote employees go a long way.

“One of the things high-performing hybrid teams do is have the skill to be able to talk about the emotional element of work, and I think it’s a skill that’s going to be required much more for everyone,” Alison Hill, author of the book Work from Anywhere told BBC. “This can mean having open and honest conversations about what’s working and what’s not in the hybrid office.”

Work allocation, mutual respect, and rewards can take a cue — evolving in their own right. Proximity bias is not a “trivial” concern of measuring productivity. It shrouds workers in a veil of invisibility; impacting some more than others.

The question, then, is how to make workers visible within the office and beyond. The new way of working has to be inclusive, fair, and aware. The truth of bias and its challenges can perhaps be another reckoning in this revamp of work culture.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Can We Move On: From the Trope of the ‘Controlling’ Girlfriend