Fertility Decreases With Age; We Can Say It and Still Fight Pressure to Procreate

Acknowledging biological facts will help us find better solutions to gender inequality.

When you’re in your mid-30s, you find yourself talking a lot about fertility. And I sense, among women in this age group, a frustration — with either the years and years of patriarchal pressure to pop out a child, or the years and years of parents prizing achievement, only to pull a bait-and-switch overnight and care only about conception.

Online, and in friend groups, the frustration has bubbled over into a backlash against both — a ” you do you, and trust your body” movement aimed at staving off worry over declining fertility. Relax, friends say — it’ll happen when you’re ready. Fertility is more about health than age, blogs claim. Statistics mean nothing at an individual level, the message implies. It’s a movement rife with anecdotes of successful post-35 conception, testimonies to the power of egg freezing, and marvel over the incredibly empowering fertility treatments available to women in the 21st century.

But this rhetoric is just as damaging as the pressure to conceive, ready or not, at a young age (or at least as young as you currently are, tick-tock). One peddles women false fear; the other peddles false hope. Both hold women’s reproductive capacity as the ultimate concern and achievement, they just differ on when and how it’s right for women to become mothers.

And both contort scientific fact out of all recognizable shape to suit their argument.

*

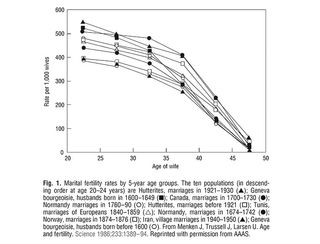

While medical terminology is wildly patriarchal and insulting to women in general, “geriatric pregnancy” — the lexicon for conception after age 35 — is particularly hurtful. That doesn’t mean the biological facts that underpin the phrase are untrue. It is an indisputable fact that women’s fertility tanks after age 35. Eggs in general, and genetically healthy eggs specifically, become fewer.

Source: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

That doesn’t mean conception is impossible within that age range, but it does mean conception is more likely to be difficult, the ‘trying’ more drawn out, assistive technology more necessary. It also doesn’t mean there aren’t women over 35 who have no trouble conceiving at all; each point on the graph above is an average, representing a bell curve that reflects the fact that some women in this age group will have no trouble conceiving, while others will find it impossible; most will find it less easy to conceive than they would have at a younger age. All groups along this 35+ bell curve are more likely to lose pregnancies, to experience complications like hypertension, gestational diabetes, and placenta previa during pregnancy, to stillbirth, to give birth prematurely, and to have babies with chromosomal abnormalities than they would have at a younger age.

These facts might be disguised by comparison to peers, though, rather than to one’s younger self, or within small circles that don’t reflect statistics with the same accuracy that large and diverse groups do. These facts might be mitigated or exacerbated by better or poorer health. But while good health is important for the proper function of all biological processes, including reproduction, it “does not offset the natural age-related decline in fertility,” according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

In other words, age is the biggest factor responsible for diminishing fertility. And no amount of anecdotal evidence of younger women having difficulty conceiving, or of older women having totally easy, healthy pregnancies, or trust in oneself, can change that.

It’s not a fact that feminists like to admit, however. The backlash against pressure to bear children young is primarily meant to justify delays in childbearing that allow (some) women to obtain (some of) the experiences, financial security, and freedoms traditionally reserved for men. Admitting that biology simply doesn’t play ball with this vision for equality is unpopular, hushed, and papered over in girl-power pablum, even as it remains inescapably true.

Where the backlash has succeeded, however, is bringing into slow focus the fact that biology does not spare men either. Men’s fertility also, inescapably, declines with age and is equally responsible for difficulty conceiving and carrying a healthy pregnancy.

Men’s fertility starts declining notably between 40 and 45. It is not, perhaps, as stark a decline as women experience, but older sperm is — on average, for most people — more difficult to conceive with than younger sperm. Sperm motility — that is, the ability of sperm to travel through the female reproductive tract to reach the egg — diminishes, meaning less likelihood of fertilization. Semen volume also diminishes with age, to similar effect. And sperm, like eggs, diminish in genetic quality with age, making miscarriage and stillbirth more likely, and certain neurodevelopmental and mental health disorders among offspring more likely, the older the father gets.

Unfortunately, this effort to spotlight men’s equal contribution (or disadvantage) to conception is often overshadowed by equal, uncritical praise for the advances in medical technology that have enabled women greater control over their fertility.

But that control is questionable.

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) — procedures like IUI and IVF — have been a doubtless boon to countless women who want biological children. But, like good health, ART cannot fully offset the effect of aging on fertility. Women aged 29 and younger who undergo IVF are roughly twice as likely to conceive and bear a child after one round of IVF as women aged 35 to 39, according to Australian data. Between that latter age group and women aged 40 to 44, that likelihood halves again for conception and birth after just one round.

Neither do options like egg freezing or egg donorship offset aging. While using a ‘younger’ egg — whether your own or someone else’s — can avoid the genetic degradation that occurs with age, eggs are only part of the calculus of conception. The age of the sperm is still a factor, as is the age of the woman’s body in general; a woman over 35 has a lower probability of getting pregnant from the same number of preserved eggs than a younger woman. Plus, for many men and women, part of the joy and interest in conceiving is to have a biological child, which one can’t do with egg donorship.

Finally, all of these procedures and options, when described by and advocated by people who have not undergone them, seem to ignore the peculiar kind of emotional, physical, and financial hell that can characterize the experience and can leave one feeling less in control than out of control. ART procedures are not without serious health risks to the women who undergo them, and the costs of ART, egg donorship, egg freezing, and other related fertility-enhancing or -preserving procedures are often exorbitant, making them available to ultimately very few women. No strength of body mitigates that.

*

We need a new model for empowering women to take control of their fertility and the rest of their lives. One that includes educating both boys and girls from young ages about fertility, so they can go into adulthood with all of the information they need to make the right choice for themselves and any partner(s), with a full understanding of tradeoffs. One that rethinks traditional career arcs, which have been modeled upon workaholic men with stay-at-home wives, to facilitate conversations and planning of a career path that allows for conceiving, pregnancy, and childrearing with fewer tradeoffs. One that sees policies enacted that recognize both genders as equals in the home and in the workplace. One that sees policies enacted that facilitate alternative paths to parenthood, like surrogacy, in ways that balance combating exploitation with inclusive and easier access.

Above all, we need a model that makes clear the choice not to have or the inability to have children is not a reflection on a woman, her body or her success. Conception, pregnancy, and childbirth are all difficult. The average female body might possess the theoretical capacity to become pregnant, but the eggs and sperm and organs and stars often do not align.

In other words: bearing children is not what women are built for. False empowerment narratives of ‘trusting your body’ to conceive, no matter what your age, rest on the same deeply reductive belief — that women are built to conceive and bear children — that underpins the patriarchal view that women can and should only achieve self-actualization through motherhood. It’s time we leave behind both myths — the one that denies aging’s effect on fertility, and the one that fears it. Only then can we grapple with the facts of fertility and reshape the world to both support it more, and care about it less.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

What Does ‘Community Transmission’ Mean, and Why Does It Matter?