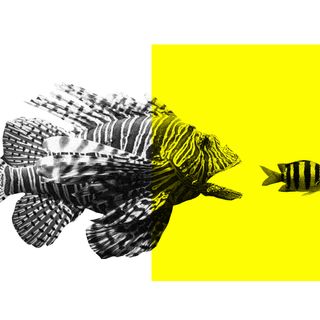

The yellows, greens, and reds of coral reefs are fading away as bleaching events transform the Australian Great Barrier Reef. Even fish communities residing within them seem to be losing their color as their ecosystems drastically change, according to new research.

“Our findings suggest that reefs may be at a critical transition point and might be poised to become much less colorful in the coming years,” wrote marine ecologist Chris Hemingson and his James Cook University colleagues in their paper. Published in Global Change Biology last week, their study analyzed data around coral colonies in the secluded Orpheus island, located in the middle of the Great Barrier Reef — the largest living structure in the world. They looked at the diversity of colors in communities found near healthy reefs and compared it with other regions shouldering the impact of heatwaves, algae influx, among other issues, over a period of 27 years.

“As these complex corals become rarer, on future reefs impacted by climate change, fish communities may become duller,” wrote the researchers. “…as the cover of turf algae and dead coral rubble increases, the diversity of colors declines to a more generalized, uniform appearance.” In other words, the spectrum of colors is being bleached to leave behind shades of white and grey — among the reefs as well as the fish communities living within them.

A crisis has been playing at the heart of Earth’s largest coral reef system for decades now. Bleaching events have picked up in intensity, a cycle fueled by carbon emissions and the sobering saga of climate change. Corals can survive a bleaching event — characterized by unusually warm sea surface temperatures during the summer season or disturbances like cyclones — but the environmental charge changes the make-up of the reefs. Just 2% of the Great Barrier Reef currently remains safe from mass bleaching events that have unflinchingly impacted the ecosystem over 30 years.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Scientists Are Using a Stock Market Theory to Save Coral Reefs

We know an organism’s color is linked to its immediate environment. Experts have noted much of the “aesthetic and intrinsic value humans place on coral reefs (a core ecosystem service they provide) is based on this extreme diversity of colors.”

Color is important to fish; they use brightness to stand out, attract males. In other cases, their neutral tones help them avoid predators by blending in. The bulk of the new research, however, notes that less complex reef structures may attract less colorful fish communities. In other words, coral bleaching might be driving away colorful fish, leaving them more vulnerable, exposed, and habitat-less. “A colorful fish blends into a colorful reef, and if you’re brightly colored in a drab environment you may not fare so well in avoiding predators and things like that,” said Hemingson in an interview.

Moreover, owing to the loss of branching corals that would have provided shelter to fish communities, the survival of the species is impacted too. “Having places to hide from predators may have allowed reef fishes to evolve unique colorations due to a reduced reliance on camouflage to avoid being eaten,” Hemingson added in the press release.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Coral reef structures may still survive and grow resilient to warmer temperatures. But colorful, brilliant fishes would end up becoming increasingly rare in the near future.

“Future reefs may not be the colorful ecosystems we recognize today, representing the loss of a culturally significant ecosystem service…in a human context, loss of these colorful species may trigger a broad range of human responses, including grief,” the researchers noted.