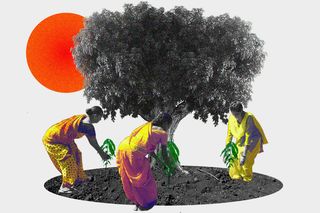

Forests Are Key to Combating India’s Climate Crisis. Here’s How Local Communities Are Regrowing Them.

Landowning communities in vulnerable areas are adopting holistic, long-term models to reforest barren land and conserve water.

In Jawhar, in the Palghar district of Maharashtra, summers are hot, dry, and brown. For the unwary, the midday sun carries the assured promise of a heatstroke. But under the Mahua tree, the wind is cool, and the ground is perfect for an afternoon nap. It is here that Nausu Dhawalu Morgha tells me about his village with perceptible pride: “The name of my village is Dabosa, but we fondly call it Dhab-Dhabaa. That’s how it sounds when the big, fat drops of rain fall from the sky. Tourists come from all over to see the giant waterfalls and the lush green beauty of Jawhar in the monsoons.”

I struggle to picture Jawhar as Morgha describes it. Could this dry, cracked, dusty, half-desert really also be a place of gushing waterfalls and overfull lakes?

Jawhar is but a small, brown blip amidst 97 million hectares of similarly barren land. Nearly 30% of India’s land is undergoing a process of desertification. The soil on this barren land is steadily degenerating into a significant source of carbon emissions. Any effective solution to mitigate climate change and the farming crisis must seriously tackle the issue of all this degraded land.

I spoke to local communities in three regions with degrading land – Palghar, Satara, and Ahmednagar – whose efforts to transform their land can show us the way out of this crisis. Where traditional land-use practices have fallen short, these communities are turning to the abundance and stability of forests. Their models of forest revival demonstrate the efficacy of holistic interventions that rebuild a mutually beneficial relationship between small landowners and their land.

Palghar: The rain pours but the water vanishes

From June through September, Jawhar receives 3000 mm of rainfall. Yet, by October, most of this water disappears, leaving the residents of Jawhar desperately parched.

Jawhar’s acute water scarcity can be largely blamed on the hydroecology of the region. Most of the 3000mm of “dhab-dhabaa” rain cannot penetrate the compact basalt that lies beneath. The water that manages to penetrate is likely to hit one of the many fractures underground and drain away instantly. It doesn’t help in the least that, over the past two decades, the forests in this region have disappeared to fuel the timber trade.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Women Activists Never Get Their Due Despite Being Critical to Nature Conservation

The population of Jawhar includes people from various Adivasi groups who grow rice and a few vegetables in the monsoons. But come October, the water is gone, farming is impossible, and they spend most of their time raising cattle and looking for water.

A 2018 report published by Niti Aayog found that nearly 600 million people (almost half of India’s population) face extreme water scarcity, with over 70% of water being contaminated. The country is currently facing, without exaggeration, the worst water crisis ever.

In Jawhar, much of the government’s efforts to conserve water have been woefully ineffectual. Without regard for the hydroecology of the region, the government has built wells on “discharge zones,” where no water collects. Furthermore, ignoring the annual water needs of each village, the authorities have built check dams that are too low to hold water through the summer months.

In the absence of competent community-led government interventions, NGOs and non-profit organizations play an essential role in ensuring the survival of vulnerable communities. In Jawhar, for example, The Raah Foundation has closely studied the ecology of the region for the past decade to improve existing government infrastructure and build new check dams and wells. Raah’s field team comprises over 30 locals whose efforts conserve over 640 million liters of water annually.

On Morgha’s 10-acre strong land, Raah has built a 26-foot well that can hold water for most of the dry season. The soil on Morgha’s land is slowly coming back to life and currently supports a massive plantation of fruiting trees, timber trees, bamboo, medicinal plants, wild endemic species, and various grasses. These species will soon provide Morgha and his family with a steady income throughout the year.

Once established, a forest requires negligible irrigation and minimal care to sustain itself. Mature forests are also the most intelligent systems of water and weather management. In deforested and water-scarce areas, the revival of forests is vital to the survival of its human communities.

Satara: The gaur ate my farm-work

“Do you think it’s fair that we, [the Malki (private forest land) owners], face all the pressure of climate change and yet must shoulder the responsibility of restoring the ecosystem?” asks Ravi Nare Lad, a resident of Bopoli village in the Satara district of Maharashtra.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Conservation Efforts Must Integrate Indigenous Perspectives

The past few decades have seen the steady degradation of Malki land accompanied by the growing distress of landowners. Since the 1960s, the Malki forest owners practiced a form of shifting cultivation involving the cyclic felling of trees for timber. Cleared land was either reforested with timber trees or used to farm rice, naachni, and other grains.

This practice of shifting cultivation came to an abrupt end in 2008 with the declaration of the Sahyadri Tiger Reserve. The reserve includes over 2000 acres of Malki land and has a strict ban on tree-felling. As a result, the Malki landowners had to give up timber harvesting and rely solely on farm income to survive.

The establishment of the tiger reserve led to a significant rise in gaur and wild boar populations, as they now had a larger habitat and reduced threat from hunters. Soon, these wild animals began to forage into Malki land to the despair of local farmers. Crop losses to wild animals became so widespread that many gave up farming. Around the same time, farmers from the region migrated to Mumbai or Pune in search of better jobs. Labour in the villages dwindled, and, as a result, most of the 2000 acres of private Malki land lies barren and unused.

In 2012, Lad became one of the first landowners to work with the Wildlife Research and Conservation Society (WRCS) to restore his 6-acre piece of land into a forest. His land now houses a healthy population of fruiting, medicinal, and commercial trees whose valuable produce hangs high above the reach of hungry animals. Once established, the lower layers of the forest will provide plenty of food for hungry animals.

News of Lad’s transformation soon spread across town. Today, WRCS has reforested over 400 acres of Malki land in 16 different villages and hopes to bring 1500 more acres into their care. Their model of reforestation around wildlife reserves brings together the goals of economic development, conservation, and ecosystem restoration.

“I am ready to be patient. I may not reap the benefits of this forest in my lifetime. But I know that we are leaving something worthwhile for our children and their children… I just hope the rest of the country realizes that we are leaving something worthwhile for them as well.” says Lad with a delicate mix of hope and austerity.

Ahmednagar: Overwhelming chaos

The past decade has been one of the most turbulent for Indian farmers. More than half of India’s farmland is unirrigated and wholly dependent on the whim of the monsoons. Since 2016, over 36 million hectares have been affected by water-related disasters, costing farmers over 29,000 crores. According to a survey conducted by the Centre for Study of Developing Societies in 2014, 76% of farmers preferred some other work, and 61% wanted jobs in cities for better education, health, and employment.

Squatting on her field, pulling out plump pink onions, Nanda Suresh Dhawale in Dhavalgaon, Ahmednagar, tells us of the uncertainty plaguing her family. “We can never know how much we will be able to harvest. We’re lucky if we reap even half of what we sow. In the last five years, the rains have become very unpredictable. The borewell water used to last us until the monsoons. But now, there are so many borewells that sometimes, we don’t have water to last until March.”

However, Dhawale’s family has not lost hope yet. With the help of the NGO Farmers for Forests (F4F), they are afforesting 2.5 acres of their 5.5-acre land.

F4F works to protect and increase forest cover in India using the Payment for Ecosystems (PES) model. Under this model, farmers and rural landowners are given semi-annual cash payments in exchange for implementing actions that nurture young forests or protect the biodiversity of existing ones. In the free market, individuals who create and maintain ecosystem services (freshwater, biodiversity, clean air, fertile soil, and so on) receive nothing in return for the tangible benefits these services provide to society. PES intervenes to remedy this market failure, aiding the transition to green livelihoods.

F4F’s model of afforestation does two things at once: It creates and maintains forests while providing farmers with additional income, livelihood security, and resilience.

Soon Dhawale’s land will house a variety of fruiting, medicinal, commercial, and native junglee trees, offering year-round income and much-needed resilience in the face of increasingly unpredictable weather patterns.

A human community is only as strong as the land on which it lives. The high cost of unhealthy land is borne disproportionately by those whose survival remains at the mercy of the rain, the soil, and the temperature.

Yet, their misfortune is sparking an important change in land-use practices across the country. It is crucial that we take notice. The people most vulnerable to climate change stand to become one of the most powerful forces for its mitigation.

Jahnavi Jethmalani is an independent writer who explores the intersection of human well-being and ecological health.

Related

Gender‑Based Violence Increases During Floods, Extreme Weather Events: Study