Study: Students Deal With Stress Better When They Think They Can Get Smarter

Students who think intelligence is innate struggled more.

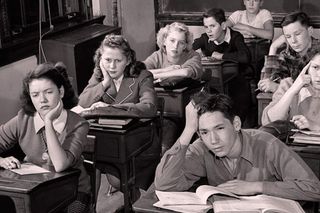

A new study adds weight to the popular theory that thinking of intelligence as something that can be cultivated with time and strategic effort helps kids be more resilient in the face of stress and adversity.

This kind of thinking, coined “growth mindset” by Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck, contrasts with “fixed mindset” — the belief that intelligence and skills are innate, unchangeable traits. Global education reform has, in large part, focused on efforts to instill a growth mindset in children. This new research, published in the esteemed journal Child Development, supports such policies, as it found students’ mindsets determined how well or poorly they coped with the stressful transition from school to high school, especially if and when their grades dropped.

The researchers tracked 499 students from two public high schools in the US state of Texas during their first semester of ninth standard. The team established students’ mindsets — growth or fixed — and analyzed students’ ability to handle academic pressure through daily surveys and saliva samples that measured levels of cortisol – the body’s stress hormone.

The team found grades dropped for 68% of students during their first three months of high school. However, not all became highly stressed by this; only students with fixed mindsets became anxious when they underperformed. These students also had difficulty coping with daily stress. Researchers recorded high cortisol levels in fixed-mindset students lasting throughout the day after an academic stressor; students with a growth mindset had high cortisol levels on the day of the academic stressor that then normalized by the day after, possibly because their growth mindset may have led them to proactively begin problem solving.

And tellingly, even when fixed-mindset students had good grades, they reported feeling “dumb” one out of three days.

“Declining grades may get ‘under the skin,’ as it were, for first-year high school students who believe intelligence is a fixed trait,” says Hae Yeon Lee, a UT Austin psychology graduate student and the study’s lead author. “But believing, instead, that intelligence can be developed — or having what is called a growth mindset — may buffer the effects of academic stress.”

While this study focused on the transition between eight and ninth standard, there’s nothing to suggest the academic stress kids experience in this shift is distinct from academic pressure at other points. For many students, the problem of poor grades is unlikely to be helped by more pressure from parents and teachers, because not only do students with fixed mindsets not know how to improve their performance — they don’t believe they can.

Luckily, there’s a way to encourage growth mindset in kids, even in kids with fixed mindsets: strategic praise. Praising effort and strategy, rather than outcome, is, Dweck says, the most effective way of promoting growth mindset, and through it, kids’ ability to rebound from setbacks and even failure.

It’s an important insight in India, where one student commits suicide every hour, according to a Quartz report earlier this year: “Although there was no exact set of causes outlined, failure at examinations accounted for nearly a quarter of the cases.”

“More students might thrive if schools carefully selected appropriate challenges, and provided students with growth-oriented belief that, with the right resources, they could continue to develop their abilities to meet reasonable demands,” says co-author David Yeager, a UT Austin associate professor of psychology.

Related:

Related

The Younger Kids Are, The More Thoroughly They Consider Their Decisions