Have Humans Evolved to Be Cheaters?

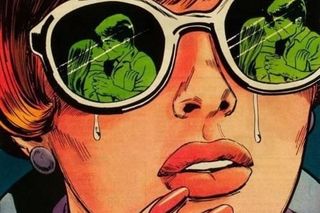

We want bonded partners, but will always desire others at the same time.

The ‘cheater’ has become a cultural trope, with magazine articles telling you 5 Tell-Tale Signs Your Partner Is A Cheater, 6 Things You Didn’t Know About Cheaters, According To Science, and 10 Signs That Your Partner Is Cheating. There’s a pervasive idea of the cheater as a personality type, to be avoided if you want a happy, infidelity-free relationship.

But what if humans just weren’t built that way?

Evolutionary psychology experts like Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá, co-authors of the book Sex at Dawn, theorize men and women both have biological motivations for cheating while maintaining a monogamous relationship. Male animals, including humans, have an evolutionary drive to have as many offspring as they can with different mates, while females are motivated to seek out mates with superior genes in order to increase the genetic diversity (and chances of survival) of their offspring. But some animals, humans included, have also evolved, both socially and biologically, to want the security of monogamous relationships; we may still feel jealousy or betrayal if we’re cheated on, wanting our partners to be faithful, while also being sexually attracted to other people.

While this isn’t an excuse for people to cheat, it does suggest humans will always have these opposing biological motivations creating a tension within ourselves and our relationships.

Monogamy is uncommon among animals, with fewer than 5 percent of mammals staying with the same mate. Humans evolved towards monogamy mostly because babies are, in a word, helpless. Sixty million years ago, as our primate ancestors began the long process of evolution to the modern human, their brains, and consequently their skulls, were growing increasingly large. While that was certainly an improvement, it meant that babies had to be born earlier in their development in order for their heads to fit through the female birth canal. This is why baby gorillas, chimps, and humans are born relatively helpless — unlike sea turtles who immediately fend for themselves. Parents of primates generally need to spend more time caring for their offspring after birth.

Because they needed to be nursed, carried, protected, and fed for several months, if not years, pairs or groups of parents raising the infant became necessary, Ryan and Jethá write. But since male primates didn’t like to be responsible for offspring that wasn’t theirs (an understatement — this usually resulted in infanticide by angry males), pair-bonding became a necessity. Monogamous pairs seemed to be the solution for decreasing male-male competition while still ensuring enough resources for the offspring. But this didn’t mean that primitive man didn’t cheat.

Related on The Swaddle:

Marital Infidelity: Why It Happens

Monogamy was a convenient way to ensure that, in the genetic competition of evolution, one’s offspring reached maturity. It meant staying together basically ‘for the sake of the kids,’ but not necessarily being sexually faithful to one another. Our motivations for reproduction, Ryan and Jethá argue, drive us to seek partners outside of our monogamous relationships.

Reproduction required little investment for males; females, on the other hand, have to choose between the security a male partner may provide, and superior genetic qualities — because as Daniel Kruger, an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Michigan, has pointed out, it’s rare for a man to provide both.

“One long-term strategy is to settle down and have a long-term relationship with a guy who’s a reliable, stable provider, but then have an affair on the side with a guy who has phenotypic qualities and can provide that high-quality genetic investment,” Kruger has said. And genetically, women are predisposed to have this kind of ‘back-up plan,’ which researchers at the University of Texas refer to as the “mate-switching hypothesis.” But in order to maintain the status quo of the monogamous relationship, both men and women have to resort to what Kruger refers to as “strategies and counter strategies.” In other words, humans just try to not get caught.

Not convinced? These same competing impulses are found throughout nature, even among the animal kingdom’s erstwhile paragons of monogamy: birds.

With an estimated 90 percent of feathered species staying monogamous, birds have also been found to be serial cheaters for the same evolutionary incentives humans have. For decades, scientists believed that birds’ social monogamy during breeding season meant that the bonded pairs were prone to loyalty. But further genetic and behavioral research has shown that up to 75 percent of the offspring in a population could be from “extra-pair copulations.” Adultery, jealousy, and cuckolded partners abound, from indigo buntings, to yellow warblers. Even wandering albatrosses, who return back to the same partner every year after months at sea, aren’t always sexually faithful, with 14 to 24 percent of chicks fathered by a male who is not the mother’s life partner. Clearly, social monogamy for birds is strictly separate from sexual monogamy, a far rarer occurrence.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Balancing Act: ‘He Wants To Explore Polyamory; I Don’t’

Regardless of species, it seems that cheating while monogamous is possibly the most ideal situation for bonded pairs. The male gets to spread his genes as far and as wide as he can, with next to no repercussions, thus ensuring reproduction with at least one female; and the female gets to increase the genetic diversity among her offspring (in case some have genetic defects, others can survive) without risking the loss of resources provided by her mate. Ideally, males will help provide for all of the female’s offspring (unaware that they might not all be his), and females will be ignorant of their male partners’ mating with others.

It could be great, if we could all be open about this and okay with the idea of raising children regardless of whether they’re biologically ours. However, child rearing à la Plato’s idea of collective parenting feels like an unattainable dream. Like so many things about humans, we must manage conflicting impulses — genetic incentives to stay in monogamous relationships, and ones that lead us to cheat.

In her recent book, The State of Affairs: Rethinking Infidelity, couples’ therapist Esther Perel argues that being honest about our desires is essential for monogamy to survive. Our society has demonized the idea of ‘the cheater’ as someone who commits an unforgivable act, but Perel argues instead we need “a more nuanced and less judgmental conversation about infidelity,” one that acknowledges “the intricacies of love and desire don’t yield to simple categorizations of good and bad, victim and culprit.” Shifting our understanding of monogamy — from one with stringent rules and repercussions for cheaters, to one that’s open about our needs — might be the only way to reconcile these conflicting drives within us. ‘Alternative’ lifestyles like polyamory or collectivist parenting might be as proto-human as they are progressive, offering us a way to work through our feelings of jealousy, possessiveness, or betrayal. Only primitive man would argue that the best way to enjoy the security of monogamy is by living in complete oblivion.

Nadia Nooreyezdan is The Swaddle's culture editor. Since graduating from Columbia Journalism School, she spends her time thinking about aliens, cyborgs, and social justice sci-fi. She's also working on a memoir about her family's journey from Iran to India.

Related

What It’s Like To Live With: A Partner With Postpartum Depression