Are There Any Benefits to Holding Back an Orgasm?

From tantric sex to edging, a variety of sexual practices involve stopping just before climax.

The orgasm is venerated — definitive. For both men and women, cultural narratives tell us, the orgasm is a central experience. Not being able to have one is called a dysfunction. But what if one can have orgasms, and just chooses not to climax? Are there any benefits or downsides to holding back an orgasm?

Coitus reservatus, or holding back an orgasm, is an ancient sexual practice, dating back to ancient Roman times in the West and chronicled in the East in a 4th-century AD text in China, which recounts the myth that the goddess Su-Nu instructed the Yellow Emperor that withholding orgasm while having deeply penetrative and slow sex was the best way to live.

Today, coitus reservatus exists in a variety of forms, namely edging, tantric sex, karezza, and orgasm denial — and probably many more, given the ingenuity of human sexual practice. But control seems to be the crux of any benefit from holding back an orgasm via these practices — gaining control, losing control, and sharing control.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Sexual Dysfunction Looks Like When Female Sexual Dissatisfaction Is the Norm

Let’s start with edging. Now a type of foreplay, edging has its roots in a therapy developed by urologist James Semans to help men struggling with premature ejaculation (roughly 30% of men everywhere). The basic gist of edging is stimulating yourself (or a partner stimulating you manually or a couple stimulating each other via intercourse) to the brink of orgasm, then stopping, squeezing, or backing off — only to repeat the advance, pause, advance, pause. For some, this process is intended to end in orgasm — which anecdotally, is much more intense after all the time spent ‘on the edge.’ For others, especially couples, edging is a way to make sex more about the journey and less about “that great prize at the end,” Dr. Holly Richmond, psychologist and licensed sex therapist, told Men’s Health. And for men struggling with premature ejaculation, it’s about gaining more control over their physical responses to stimulation.

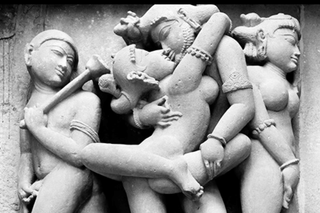

Control infuses tantric sex practices a little differently. Tantric sex twisted into being over centuries out of Tantra, esoteric philosophies found within both Hindu and Buddhist traditions that may (or may not) have had an erotic element, but weren’t particularly devoted to sexual practices. By the late 19th century and early 20th century, however, as colonialism facilitated cultural exchange, tantric sexual practices coalesced via a “strange feedback loop” writes Peter von Ziegesar in an essay on coitus reservatus for Aeon, “in which Indian practitioners and gurus [began to] take their ideas from Western scholars and sell them to Western disciples thirsting for initiation into the mysteries of the East,” he quotes David Gordon White, a professor of comparative religions at the University of California, Santa Barbara, as explaining.

Some of these tantric sex practices focus on men’s ability to hold back orgasm, which many argue produces a transcendence that facilitates greater insight into — in alternative phrasing, control over — the subconscious. von Ziegesar describes a demonstration during a tantric sex conference in which a young man is sexually stimulated by a female partner while choosing not to climax but instead maintain a plateaued state of arousal. He “seemed to go into an altered state. At one point during the pummelling, the audience was invited to ask him questions. At first, the queries were anodyne. ‘How are you feeling?’ ‘Good.’ Then someone asked: ‘Is there anything you want to tell your parents?’ To which he responded: ‘I want to tell them to leave me alone!’”

Related on The Swaddle:

The Importance of Orgasms, From Women Who Don’t Have Them

Another such tantric-related practice during the 19th century was karezza, which has gained new attention in recent years. Karezza, from the Italian word “to caress” and originally developed for heterosexual couples, boils down to having slow sex that does not culminate in an orgasm, but instead focuses on touching and emotional intimacy. Within karezza, and similar practices, sex, so often defined by male climax and hence, by male control of intimacy, is redefined as mutual control — and thus, mutual enjoyment — of sexual pleasure, as both partners work together to maintain the plateau stage of arousal. In theory, von Ziegesar points out, this shared control without the aim of orgasm — or even tantric acts geared toward men holding back orgasm — creates more opportunity for other forms of intimacy, such as eye-gazing between partners, which carry a host of proven benefits related to bonding, empathy, self-awareness, memory, and positivity.

By contrast, orgasm denial is a version of holding back orgasm that’s all about an imbalance of control. It’s a sub-dom kink in which one partner (the dom) stimulates another (the sub) to the brink of orgasm, then purposefully stops, denying the former release; sometimes this pattern is repeated. (There are a lot of variations on this kind of sex play, but that’s the gist.) While kink, in its purest form, ensures subs control over their experience, part of the satisfaction in, well, a lack of satisfaction, is the loss of control over the stimulation and climax. As one essayist writes about orgasm denial (which she incorrectly describes as edging) leading up to the “best orgasm [she] ever had” for HuffPost: “He was absolutely enjoying himself in making me wait. And I was too. The anticipation was incredible. … I was in a trance-like state or [sic] extreme arousal and desire when I was finally allowed to climax.” Allowed being the operative word.

Unfortunately, because of societal squeamishness about sex — particularly in the traditionally puritanical U.S., a world leader in scientific research — the above benefits are mostly theoretical and anecdotal; there’s very little funding or encouragement for scientists to study anything to do with sex, including orgasm. This means there’s a lack of scientific insight to answer this question, leaving the average, sexually active person at the mercy of Reddit threads, wellness gurus, and self-proclaimed sexperts.

“The amount of speculation versus actual data on both the function and value of orgasm is remarkable,” Julia Heiman, director of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction in Bloomington, Indiana, told Kayt Sukel for her essay on scientific research into the female orgasm for New Scientist.

And what we do know about not climaxing is focused on failing to achieve orgasm (a turn of phrase that sets up the orgasm as the ultimate goal and arbiter of intimacy), leaving us with very little knowledge about what happens when we are aroused, but purposefully don’t come.

Still, we do know a bit about what happens when we do climax — and what the benefits of orgasms might be. Several studies suggest that more orgasms, up to a point, correlate with longer life spans. (Of course, that could just mean healthier people are likely to be sexually active.) We also know that when we climax, the brain (among other responses) floods its reward center with dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with motivation, reward, and addiction, among other things.

Ultimately, few studies suggest holding back orgasms has health benefits — but none describe any health damage. Myths like “not climaxing will make your sperm back up” are simply, laughably false. This means most of the benefits of holding back an orgasm are deeply personal and tied up in our deepest desires and ideals around what a sexual experience should be. Ultimately, if withholding orgasm — through edging, tantric sex, karezza, orgasm denial kink, or other practices — works for the individual (and any partner), they should do it; if it doesn’t, they shouldn’t. Science has yet to give us a reason to elevate orgasms to the place they so clearly hold in our societal fantasies, which puts control — however different people prefer it — decidedly in our hands.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Coronavirus Isn’t the First Epidemic to Start in Asia, Won’t Be the Last