This week, a 2019 Vanity Fair video of Hasan Minhaj taking a lie detector test went viral, in which Minhaj is asked to rate the attractiveness of white Hollywood actor Dax Shepard. Giving him a 6.5 or 7, Minhaj says, “Dax is part of a thing, where in show business, there’s this whole movement of approachable white dudes, whereas with men of color it’s like Idris Elba, Henry Golding, Zayn Malik … or you work in IT. There’s no middle.”

If there’s a brown actor in Hollywood, Minhaj goes on to add, he better have a V taper (a bodybuilding term in which broad muscular shoulders taper into a narrow V at the hips) or have pecs so big and muscular they can hold a pencil between them. So, while a “schlubby” actor like Shepard may be able to make it in Hollywood, a brown actor with similar looks will have to jump through several more hoops, or more rigorously ascribe to Eurocentric beauty standards, to achieve comparable success. Minhaj concludes by saying he thinks he’s better looking than Shepard, “but I will not get the same opportunities that Dax does.”

The phenomenon Minhaj describes is not new — it’s borne out of brown male actors, especially of Indian origin, having often been sidelined into stereotypically Indian characters. They usually work in the IT sector, are socially awkward, innocently and ignorantly sexist, and hardly ever the object of sincere affection or desire from a woman (they’re always straight). Such longstanding, persistent portrayals of brown male actors have led to a conflation of the character and the actor, as if making it impossible to divorce the lack of attractiveness imposed on brown characters from the ways in which the actors who play them are perceived in real life.

Related on The Swaddle:

Body Positivity Is Excluding People; What If We Got Rid of Beauty Instead?

In order to break out of this stereotype, and the attractiveness markers it brings, brown men have to aspire to the other extreme — a complete embrace of Eurocentric beauty standards. This goes beyond skin color, to include facial features (thin and long noses, small mouths, slim faces, sharp jaws), hairstyle (tame and neat), or body type (muscular, and therefore masculine). Take Kumail Nanjiani, for example — once a quintessential IT guy in Silicon Valley, his recent bout of mainstream movie successes have also had to coincide with his recent body transformation.

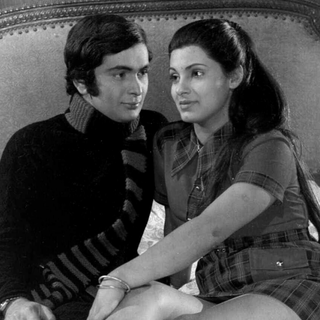

These extremes exist because we don’t really have any precedent to consider a regular-looking brown man attractive in Hollywood. Even Bollywood, where beauty standards for men are slowly expanding to include more actors in romantic leads, the norm still remains tall, dark and handsome, preferably with a hint of Eurocentric features sprinkled in. That’s why Minhaj advocates for “a middle” in the Vanity Fair video, as a place that all the brown actors who are not Zayn Malik and who are not the quintessential IT guy stereotype, can hold, and where they can be cast.

But it’s not just a middle that needs to be created, it’s multitudes — of our definitions of attractiveness, of desirability, of Indian-ness. The hotness we ascribe to brown male actors, which then subsequently determines their typecast trajectory, has little do with their actual appearance, and everything to do with the racist stereotypes they’re made to fit into. In order to move away from the practice, it’s not the actors that need transformation, it’s their roles.