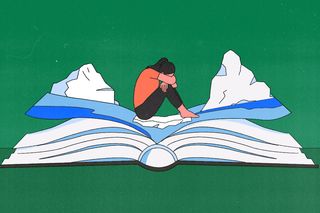

How a Robust Climate Education Curriculum Can Address Young Adults’ Eco‑Anxiety

According to a study, textbook wordings that portray climate change as ‘uncertain’ increase students’ doubts about their future.

In 2007, The Eagles crafted a melody. “No more walks in the wood/The trees have all been cut down,” they sang. “And you, for ill, and I/Am only a passer-by.” Researcher Justin Lawson argued it was about “solastalgia,” Greek for eco-anxiety. The song captured the emotional and existential distress of a changing environment, altering one’s sense of identity.

The “you” here feels familiar to a generation of young adults carrying a decaying inheritance on their hands. Everyone under 40 today is expected to live an “unprecedented life”; young adults in developing countries like India are expected to face a more significant burden. A news report calls it the “triple jeopardy,” listing the fatal triad of floods, heatwaves, and droughts. The fear and helplessness of this reality translate into eco-anxiety — a feeling three in four young people relate with.

Since young adults will bear the overarching effects of climate, it becomes imperative they’re adequately taught about it. But how they look at climate change is akin to solving a puzzle. “There are only lessons that speak of problems and possible solutions. A full-fledged curriculum is still missing from the racks,” Bhavesh Swami, a member of The Climate Reality Project India, says. “Diving deep into a subject like environmental science needs time, patience, and practicality, which, unfortunately, is the missing piece.”

Outdated and baseline knowledge

“…not knowing what to do, not knowing what’s going to happen, not knowing what other people are thinking and feeling—these situations are ripe to breed anxiety in anyone…,” The Atlantic noted. In a 2020 study, researchers explained climate-related anxiety could be either adaptive (prompting activism or sustainable lifestyle action) or maladaptive. The latter may have the person feeling incapable of addressing the problem. The lack of unclear information around extreme weather events — how something like climate change affects the Kerala floods (this year or before) — exacerbates this feeling of helplessness. A green curriculum can thus become a weapon to dispel anxiety.

Despite India’s rich history of environmental resistance, climate and environmental education feel outdated and facile. Most schools do not have a specific climate education syllabus; it is subsumed under EVS. Although the Supreme Court made environmental education compulsory in formal education in 2003, its impact remains negligible.

For Disha Ravi, a thick stream of muddy water barging through the door every July felt like the norm every monsoon. She didn’t instinctively think of a larger cause; climate change was almost “a foreign concept in school.” It was only when she accessed information online that the worrying nexus revealed itself. Or take Tanmay Sinde, who finished high school in 2010, who struggles to remember if the environmental science (EVS) classes covered climate change beyond a slight mention of global warming or deforestation.

Related on The Swaddle:

Eco‑Anxiety Is Fuelled by Helplessness, Anger. Can We Turn Our Grief Into Climate Action?

“The science today tells us that climate change will increasingly cause widespread social disruption, and amplify inequalities in already-disadvantaged areas; so we can no longer frame climate change in purely technological and scientific terms, even in classrooms,” Mandakini Chandra, a climate researcher at the Centre for Policy Research, says. Most modules are generic, outdated, and frame climate change as merely a “scientific” subject, distancing people and failing to connect the human, social, and economic aspects of climate change.

As a consequence, students fail to “build a connection with nature and subsequently, build accountability towards the planet,” says Shruti Joshi, a researcher and volunteer with Friday for Future (FFF). Moreover, limiting textbooks to great environmental movements of the ‘90s, and not beyond, frames this as a past struggle, not a present one.

The knowledge gap is further widened due to class structures. There are three categories of students most likely to receive a climate education: those who speak English, those who study in “privileged” schools that include updated curriculum, and those who can access climate information on the internet.

The limited reach of these syllabi also frames climate change as a macro concern of the very privileged. Ravi studied in a public school in Karnataka; the shrinking ozone layer or a few stories on environmental movements disappeared from textbooks and conversations in high school. “Climate education is…being addressed in elite private schools or alternative schools that most people cannot afford,” she notes, which explains why a Bengal school is teaching English to students as a way to impart climate education. These children have lived near the Sundarbans’ mangrove trees for years but have a limited understanding of how climate change is linked to extreme events like cyclones.

Sylvia Almeida, a researcher who studied Indian environmental education, also noted the government’s failure to adequately train teachers to cover sustainability issues. “Teachers and students are already bogged down with routine syllabus; any new addition seems like a burden rather than an opportunity to learn,” Bhavesh points out.

Why climate change remains a “science-only” subject is a complex problem. People, young and old, view the crisis from a political and ideological lens, which explains why some textbooks fail to mention man-made causes (like deforestation or quarrying).

Joshi explains the narrow focus of the curriculum as a way to avoid misinformation, “controversy and legal issues with governments and industries.” The result is a module that may talk about the glorious biodiversity but fail to mention the impact of consumerism and capitalism.

The disagreement around climate change causes logistical limitations, which ensures that a full-fledged curriculum stays missing from the racks. The consequence is more uncertainty in children. According to a study, textbook words that portray climate change and its causes as “uncertain” or without any clear explanation triggers more doubt and guilt in students.

“It’s gut-wrenching to see people’s land taken away from them, for rivers to be poisoned, for people to face wrongful incarceration, for so much biodiversity loss and the human cost of that loss,” says Ravi.

Battling fear with knowledge

Student communities globally have demanded a curriculum focusing on climate change. In India, as many as 79% of students feel studying climate change, and environmental conservation is imperative to know what changes to make.

“Making education accessible at a younger age gives you a better understanding of the situation and lets you take action,” notes Ravi. The New Zealand government enacted this in 2019 and found that curricula frame climate change as a “fixable” problem rather than something that is beyond our control, alleviating the powerlessness and guilt.

Related on The Swaddle:

All the Arguments You Need: To Convince People That Individual Behavior Does Affect Climate Change

What would an ideal curriculum look like? For one, it would help decode the language of climate science, teach students to think about the scientific process directly. Updated information, such as insights from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a group of scientists assessing the human causes of climate change), adds to the information scope. Even experimenting with the medium of instruction, such as video or image-based, can “help students visualize the effect of rising temperatures globally and thus increase accountability,” Joshi says. In 2016, researchers looked at “artful” ways to talk about climate change’s impact on emotions, composing songs to dramatizing plays. “Science has often been presented as a book of canonical fact. We need students, and the general public, to have a stronger understanding of the scientific process,” researcher K.C. Busch said.

The overwhelming amount of information (and misinformation) on social media or news reports makes this all the more important; constantly seeing flashes of “code red for humanity” impact can spiral into anxiety without knowing the whys and hows. As P*, a geography teacher, says, “True learning happens when we feel a connection to the content and our living context. For information to become knowledge, we need to connect to it.”

It could also be helpful to know how the climate crisis is governed in India – via institutions and policies – so that students can decode climate mitigation in terms of health outcomes and development challenges. For instance, India’s Centre for Climate Education looks at the emotional experience of nature, the practicality of urban cities and climate, and ways to conserve this link. Joshi notes that students visualizing “opportunities in environmentalism” can motivate them instead of being in hopeless despair.

Chandra further argues that when the knowledge one has access to – in classrooms and the headlines – is “actionable, and focused on addressing issues in governance processes,” it can counter the adverse effects of doomscrolling.

Since the prospect of an uncertain future fuels eco-anxiety, the element of “action” and long-term solutions must find a place within the curriculum. The action can be in conservation, opportunities for green jobs, or innovations in sustainability, as unemployment and health issues also drive fear in young adults. Rising awareness about eco-anxiety can also destigmatize mental health discourse in education. A Canadian school, for instance, made it a point to include discussions about grief and despair in environmental education classes.

An antidote to uncertainty is usually the idea of getting used to something. But the remedy doesn’t apply to climate change; there’s no getting comfortable with a dying planet.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

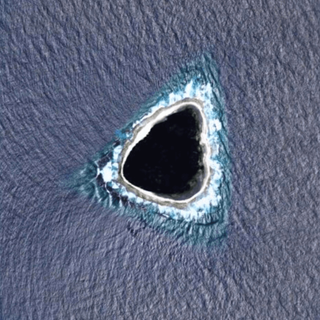

People Baffled at Google Maps Showing a ‘Black Hole’ in the Middle of the Ocean