How a Tiny Indian Owlet Was Discovered, Vanished for 100 Years, And Was Discovered Again

The Forest Owlet is now on the brink of extinction due to cattle grazing, illegal tree felling, and fuelwood extraction.

Some owls are so small, they are known as owlets. The forest owlet, a species unique to India, is one such owl. It was discovered in 1872 when F. R. Blewitt collected the first specimen of the bird in present-day Chhattisgarh. Six more specimens of the “Blewitt’s Owl” were collected until 1884 from Maharashtra and Odisha by two other collectors. Then, more than a century went by without a single legitimate record of the bird.

Alleged forest owlet records that came after 1884 — eggs, photographs, skins, or sightings — didn’t really belong to the forest owlet. One record, dated 1914, was indeed of the forest owlet but it was fraudulent — its label had been fabricated and the specimen tampered with. A collector had stolen one of the 19th-century specimens from the Natural History Museum in Tring, UK, and labeled it with a made-up collection date and location. This led to search efforts in the wrong location. With no sightings in this and other places, many believed that the bird had gone extinct.

That is, until 1997, when the forest owlet was finally found — after going unnoticed for 113 years. When American ornithologist Pamela Rasmussen exposed the falsification of the one museum specimen, she started looking for the forest owlet in its correct historical locations. On the morning of 25 November 1997, Rasmussen and colleagues set eyes on the species perched on a leafless tree in the Nandurbar district of Maharashtra.

However, now, after a dramatic journey of rediscovery, the forest owlet once again stands at the brink of endangerment. Although the bird has survived in patches of forests, all kinds of anthropogenic threats loom large over it — clearing of forests for settlement and cultivation, illegal tree felling, intentional forest fires, rodenticides, and use of owl eggs and body parts in witchcraft. The forest owlet represents the case to protect small, lesser-known species and their dwindling forest habitats.

*

In 1997, the much-awaited rediscovery of the forest owlet generated a lot of buzz. “To see a living forest owlet, living in these forests [and] hiding there for so long was really, really exciting,” recalls Farah Ishtiaq, who accompanied Rasmussen to the site of rediscovery in 1998. “We spent a good ten days there looking for the bird,” says Ishtiaq. The duo was the first to record and describe the forest owlet’s song call.

Ishtiaq then spent the next year studying the bird’s diet, habitat use, vocal repertoire, and nesting behavior, none of which was known before. She reported that the species nests in tree cavities and that old-growth trees with nesting cavities were in short supply. Her observations of a forest owlet nest after dark confirmed that, unlike most owls, the forest owlet wasn’t a night owl.

Later, Ishtiaq also conducted a survey for the forest owlet in its historical range, known from 19th-century specimens, and other potential sites in the central Indian landscape. By playing forest owlet calls she had recorded during her behavioral studies, Ishtiaq detected more owls that would answer to these playbacks. With and without the use of call playback, Ishtiaq managed to find a total of 25 forest owlets in four localities, two of which were new additions to the owlet’s erstwhile range — the Khaknar Forest Range of Madhya Pradesh and Melghat Tiger Reserve of Maharashtra.

Related on The Swaddle:

Mass Bird Deaths Are Increasing in Frequency and Magnitude. Why?

Two decades before Rasmussen, a scientific quest to find the forest owlet in Melghat had failed largely because scientists were playing the calls of the wrong species—the spotted owlet. Ishtiaq says that nobody had the faintest idea of how the forest owlet called, or what time of the day it was active.

The forest owlet’s resemblance to the spotted owlet might have further delayed its rediscovery. In 1873, British ornithologist A. O. Hume described Blewitt’s specimen of the forest owlet as: “General appearance not unlike that of [spotted owlet], but size larger and wings shorter.” Even with a specimen in hand, Hume found the two species similar. Post-independence, when Indian scientists and birdwatchers were searching for the forest owlet, they were essentially flying blind in the absence of any specimens of the bird in the country. Posters of the forest owlet that were going around at the time were later found to be flawed.

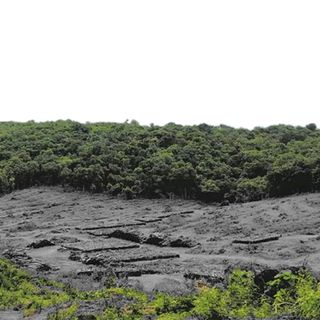

By the time the forest owlet was rediscovered, its forest habitat in central India had undergone drastic changes and was now under immense pressure from people. While surveys by Prachi Mehta in five states during 2005–07 found two new owlet populations in the teak forests of Madhya Pradesh, the search in Phuljhar, Chhattisgarh, where Blewitt had collected the first specimen, turned up empty. The forest owlet is typically found in open-canopied, deciduous forests and there, there were none left. This erstwhile forest owlet home was now cultivated land.

Wherever her surveys took her, Mehta noticed habitat disturbance from activities such as cattle grazing, illegal tree felling, and fuelwood extraction. People would cut down trees with cavities without knowing the importance of these for the owl, Mehta says. Since habitat protection was central to forest owlet conservation, involving tribal communities that depended on forests for subsistence has been at the heart of Mehta’s work with the Pune-based Wildlife Research and Conservation Society (WRCS).

In Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra the WRCS, where Mehta is the executive director of research, have been empowering tribal communities by facilitating alternative livelihood opportunities. In 2016, Mehta’s team conducted their first training for the Korku women of Madhya Pradesh and taught them how to make owl memorabilia and handicrafts. This started a conversation about owls among the locals, Mehta says, leading to awareness.

Two years later, in 2018, WRCS extended the handicrafts training workshops to the Korkus of Maharashtra. Women from four villages of Melghat, which is a stronghold of the forest owlet, participated. Since then, WRCS has also set up a permanent training center in one of the villages, named Chaurakund, where locally-acquired bamboo waste is processed by men into products depicting the forest owlet. These are then hand-painted by women, brought to Pune, and sold online or at corporate events, according to Aboli Waikar, the program manager of WRCS’s community initiatives. The tribal people get paid upon completion of the work irrespective of the sales, Waikar says.

By providing people with a livelihood tied to the owl, and through numerous outreach campaigns, Mehta and her team have rallied their support for conservation of the forest owlet and its habitat. This just might save the forest owlet from disappearing for real.

Richa Malhotra is an independent science writer. She posts on Twitter and Instagram @rich_malhotra and writes a newsletter on all things birds at tinyletter.com/RichaMalhotra.

Related

Goa Rail Expansion Will Destroy the “Fragile Ecosystem” in Western Ghats, SC Panel Says