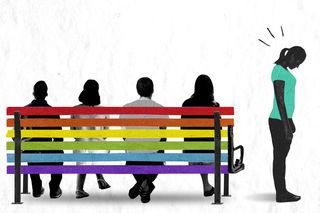

How Asexual People Feel Excluded From Queer Spaces, Complicating Their Identity

“I feel scared about expressing solidarity [with queer communities]. My identity is, by and large, defined by an absence.”

Asexuality is both straightforward and complicated to define. At the outset, it describes the orientation of somebody who doesn’t experience sexual attraction. But this is followed by many caveats: when? In what context? How do you know what attraction isn’t if you don’t know what it is? It’s why asexuality is often considered to exist on a wider spectrum than other queer identities – but this, precisely, is what makes it confusing as a label for many. Not knowing whether and where you fit in can lead to a state of limbo – not quite queer, but not quite not queer either.

Asexuality shares a particularly tumultuous relationship with queerness. Where queerness has been defined by sex – expressing it, having it, and most importantly, taking pride in it – asexuality decenters the primacy of sex in our culture.

Technically, the “A” in LGBTQIA stands for asexual – but it doesn’t always feel that way. “There’s this imposter syndrome of sorts… and it is definitely exacerbated with other queer people saying the things that make us feel insecure in the community in the first place. Things like how ‘everyone takes time to like someone’ or ‘you’re straight passing so you aren’t really queer,’” says Anandi, 25. She grew up in Tirupathi, a small town in Andhra Pradesh. She knew she was asexual long before she found the words to express it. When that happened, it was like “a switch flipped.”

“I feel scared about expressing solidarity [with queer communities]. My identity is, by and large, defined by an absence.”

But the “absence” she mentions is significant: the lack of sexual attraction is what defines her own self-identity, her inclusion, and her exclusion in many spaces, including queer ones.

“If you’re just moseying through life going the way your blood beats, a relative paucity of blood rushes might not tip you off that your sexuality is something other than standard issue. Epiphanies are structurally less likely to occur via negative feedback loops,” writes G’Ra Asim in The Baffler. It leads to a situation where queerness as an identity doesn’t feel like the home it was supposed to be for asexual people. “I just want to feel normal. If asserting myself as queer will give me that… then I don’t mind asserting myself as queer. Otherwise I don’t see the point,” says Amina*, 22, who identifies as demi-ace.

Related on The Swaddle:

Asexuality Is a Sexual Orientation, Not A Disorder

For better or for worse, most cultures are hypersexual. Some are better at repressing it than others. In India, sex is taboo until it isn’t: marriage is the line between chaste adoloscence and mature adulthood, a door behind which sex is a default assumption. This can, and is, dangerous to asexual people – particularly ace women, but this is hardly recognized or spoken about in any space, including queer spaces. Many have defined their experiences as aces in arranged marriages as “corrective rape.” And yet, there is little recognition – let alone solidarity – from within the queer community itself over this fact, owing to the fact that the violence is not visible in the same ways. Ace people are not likely to be visible just upon first glance by antagonistic forces, but they experience a lifelong culture of imposed sexual mores that feel violative.

Pragati Singh, who heads Indian Aces, an advocacy group and collective for asexual people, says that the biggest issue that ace people are yet to mobilize around is that of marital rape. While other communities under the queer umbrella advocate for the right to express their sexual attraction, the asexual resistance looks a bit different: it is to push back against compulsory sexuality. In other words it is to imagine a society in which sex and sexuality are not the organizing forces of our lives, relationships, and families, and ask that people be allowed room to live their lives in this way.

Take the fact that in 2014, the Indian Supreme Court said “If a spouse does not allow the partner to have sex for a long time without a sufficient reason, it amounts to mental cruelty.” Refusing sex within a marriage can, in other words, be reasonable grounds for divorce – which in turn carries enormous cultural and patriarchal baggage, especially for women.

When Singh mentions marital rape as an ace issue, therefore, it is in recognition of the fact that compulsory, state-sanctioned sex in the form of marriage is violent. Defining sex as essential to the institution of marriage is violent. Forging solidarities around this fact would mean that asexuality can be radical – as any kind of queerness is.

“Attending to asexuality helps us broaden our understanding of love and sex… the sexual experiences of asexual people are beginning to show that we have overly narrow conceptions of attraction and enjoyment,” write Natasha McKeever and Luke Brunning

But within queer spaces, this is often invalidated – not expressing any form of sexuality is taken to be “straight-passing,” as Anandi notes. The fact that asexuality has no distinctive, visible identity markers makes it a square peg to the circular holes in queer spaces. “The people belonging to the [queer] community also don’t know what asexuality is… it is very underrepresented,” Amina adds, describing a conversation she had with her bisexual friend who didn’t understand asexuality at all. The hypersexuality within queer spaces, moreover, makes solidarities difficult to express, let alone forge. “There’s just always so much talk about sex [in queer spaces]… if you don’t feel comfortable with it – for non-homophobic reasons, mind you – you’re wrong,” says Anandi.

Related on The Swaddle:

Body Matters: Navigating Asexuality in a Gynaec’s Office

Meghna Mehra, who heads the All India Queer Association (AIQA) and is asexual, too describes her exclusion from queer spaces for not participating in a culture of hypersexuality. “Unless we stop segregating ourselves from the rest of the community, [mobilizing around asexuality] is not going to happen. We face discrimination within the community where a lot of people think that if we’re not having sex, we’re not part of the community… Me, [as an ace person], starting AIQA [for all queer people] makes a difference.”

Mehra advocates for the recognition of asexuality as an orientation – but often doesn’t feel solidarity from within the queer community itself. “The government does not recognize asexuality as a valid sexual orientation, neither do the courts… People say there’s no discrimination against asexual people, and that ‘you can always pretend to be straight.’ But they’re shocked to hear that we face similar issues too – like forced marriages, honor killings,” she adds.

But as with most forms of queerness, it is also deeply personal. There is trouble with dating due to the notion that asexuality can be “corrected” or is just a phase. “Sometimes I wonder if I’m queer enough if I’m not having sex with another woman. I’m panromantic, I feel romantic attraction irrespective of gender identity but I don’t want to have sex, I’m totally repulsed by it. It’s very simple but people make it very complicated,” Mehra adds.

If taking ownership of queerness is to take ownership of sex and sexuality – to take pride, in other words – then there is little room left for aces in the larger scheme of things. “The whole idea of pride is different for us… because we’re not being told to be ashamed of being asexual. We’re not told it’s dirty or wrong. We’re told it’s impossible,” says David Jay, founder of AVEN. Asserting asexuality then doesn’t attract disgust or scorn – but a complete negation of personhood itself.

Most pop culture scripts don’t even have a vocabulary or language for asexuality. So steeped is the cultural conversation around sex, that even disinterest in sex is perceived as not just a joke, but as alien and non-human. “It’s hard to relate to our peers when they talk about attraction because our whole idea of romance is different… There’s so much sexual content in the mainstream, it’s very hard to come out of it and think about what exactly we want,” says Amina. Mark Carrigan, a researcher at the University of Warwick, calls this the “the sexual assumption” – “the idea that everyone has sexual attraction, that it’s this powerful force inside of you, and that it is experienced the same way by every person.”

All this creates a need to reify asexuality within narrow boxes in order to reclaim it – which then leaves many others to slip through the cracks once again.

“There’s all these notions about what the perfect asexual person is. And it almost feels like the community will only accept that version. Someone who has no romantic or sexual or aesthetic attraction to anyone and also is not interested in sex in any capacity, does not have the desire for it, is repulsed by it… all these boxes need to be checked if you want acceptance,” says Anandi. She went full circle – now choosing to identify with simply “queer” as a label owing to all the confusion. “It just gets hard to believe you have a place in this community when you fall on the spectrum and are always moving there,” she adds.

The exclusion isn’t deliberate, but pervasive nevertheless. Singh cites the example of pride parades, as an out and out celebration of not just diversity, but “diversity about sex.” “Asexual doesn’t mean they can’t celebrate sexuality… [but] that their form of claiming their identity is not necessarily a celebration of sex, or the different ways you can have sex, the different varieties of sexual expression… if you go to an event and find that that’s all it’s about then what does an ace person do in that situation?”

Singh’s approach to mobilizing around asexuality is different from Mehra’s in that she creates separate spaces for asexual people – noting that trying to feel included in queer and feminist spaces can get exhausting. “A lot of power was claimed as feminist by reclaiming our sexuality, by sexual liberation and owning terms that we used to shame. I will always stand for it, but we’ve left behind a large chunk of people who cannot claim power in this way… It feels like an asexual person is always left behind,” she says.

Taking asexuality seriously as an orientation does more than just validate ace people – it also holds a mirror up to society itself, and is a call to reconfigure politics around love, sexuality, relationships, and dignity. “Asexuality draws attention to the complete fixation we have on sex, and really brings it to the surface for all to see,” Ela Przybylo, a sexual cultures researcher at York University in Canada, told The Atlantic. The sooner we pay attention to what asexuality can tell us about radically reimagining life itself, the better our politics as a whole can get.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Many Banks in India Are Denying Work to Pregnant Women, Perpetuating Gender Exclusion