How Books, Literature Can Support Indian Prisoners’ Rehabilitation

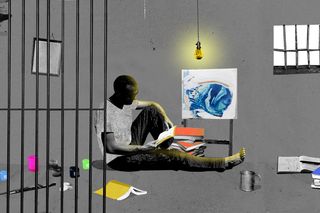

Reading inspires kinship and community, challenging the carceral state’s mandate of isolation.

We have a task for all of you. In the end of October, the first year of the pandemic, activist Devangana Kalita wrote to people on the outside. “Please ask women’s organizations and feminist publishers to donate literature, books, and pamphlets to Jail No. 6, Tihar so we can enrich and diversify the library.”

By now, Kalita and fellow activist Natasha Narwal had spent months in the crammed Tihar Jail for an unproven crime. As they penned letters of love and rage to document their anxieties, books remained a refrain in their daily lives.

Books have always contained within their pages a hope for reformation within the justice system. Only recently, the South American country of Bolivia announced a state program that allows people to capitalize on reading and education – the more an inmate reads, “the fewer days, or even weeks, they spend in prison.” A real-life “Get Out of Jail Free” card.

Resistance does lie within books for their ability to empower individuals with knowledge and empathy. But also, reading inspires kinship and community; boldly challenging the carceral state and its mandate of isolation. Countries all across the globe have increased the budget for prison libraries in recent years and experts have recognized books and education as “evidence-based prison practices” that help with reformation. A 2014 U.K. report indicated that people whose attention was preoccupied with literature and reading were 8% less likely to re-offend than those who did not have access to such courses.

Like other interventions that focus on the arts, books speak directly to the chasm at the heart of crime and punishment. They insert kindness into a justice system that is defined by cycles of oppression.

In India, however, the carceral structure is a chasm in itself, a void where millions languish due to overflowing prisons, denied care, proper hygiene, the right to defend their innocence, and the ability to reform and return back to society.

“What is specific to the Indian context regarding the harm committed in our communities is that our society is based on Brahmanical patriarchy,” Saumya Dadoo, founder of the Detention Solidarity Network, told The Swaddle last year. And, therefore, “systems of punishment rest on existing dynamics of power and work in favor of maintaining social inequality.” Government and economic forces thus benefit from the systemic oppression of vulnerable communities, and subsequently their incarceration.

Related on The Swaddle:

Tell Me More: Talking Prison Reform and Alternative Forms of Justice With Saumya Dadoo

It is no wonder then that the Indian state has often gone to the far recesses of the legal system to ban access to reading material or the very existence of libraries in Indian prisons. Last week itself, the Union government implored states to exercise caution, urging them to “keep an eye” on the books available in prison libraries, lest the act of reading will inspire “anti-national activities.” Earlier this year, activist Gautam Navlakha, arrested for his alleged role in the Bhima Koregaon violence, was denied a P.G. Wodehouse novel and, last year, activist Sudha Bhardwaj was refused John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath and Eric Hobsbawm’s Globalisation, Democracy, and Terrorism. Even the Bombay High Court ridiculed this level of surveillance, noting that the notion of it being “a security risk” was indeed “comical.”

***

Most convicts and undertrials in India are from the Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe, OBC, and minoritized backgrounds. “The majority of the prison population … did not have equal access to education and resources,” notes Baljeet Kaur, a researcher at Project 39A. She adds that education through literature can thus “help prisoners to achieve a reformed self which is ready to reintegrate into the society [and] better processes for faster release of prisoners back to the society.”

Prison libraries and education programs then become a veritable right. If society shares the responsibility of pushing the individual to a point of involvement in a crime, “it is the society and, specifically, the prison administration’s duty to provide education and skill-building opportunities to the prisoner,” says Baljeet.

These programs also become ways to decongest overcrowded prisons or shift focus from a sluggish judicial process. Bolivia’s “Books Behind Bars” program, for example, hopes to address the overcrowding of prison institutions by letting inmates out early, allowing the system to treat those within jails with more immediate care.

Education, in and of itself, also works to unbind the individual emotionally and mentally from the system; the locus of healing then lies in mental health. It is hard to empirically show the psychological consequences of incarceration; this is due to a lack of record-keeping and limited data. But a common trend, in India and other societies, is one of rising mental health issues and cases of suicide among inmates. Isolation; exposure to violence; lack of access to care; and a sterile environment that cages the individual inside concrete walls are all linked to mood disorders, depression, and anxiety. One report by Project 39A found almost 62.2% of death row prisoners had a mental illness; 11% had an intellectual disability.

Perhaps, the severity of the emotional toll is best articulated by Michel Foucault, who in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, wrote, “punishments like imprisonment — mere loss of liberty — has never functioned without a certain additional element of punishment that certainly concerns the body itself: rationing of food, sexual deprivation, corporal punishment, solitary confinement… There remains, therefore, a trace of ‘torture’ in the modern mechanisms of criminal justice.”

If the carceral institution cages the mind, rehabilitation also demands cognitive reintegration; a healing that applies to the mind and emotions too. Reading becomes one such way; for people deprived of learning and building cognitive skills before prison, engaging with reading and education is seen as a course correction.

For Mildred, an inmate at the Obrajes women’s prison in the highland city of Bolivia’s La Paz, learning to read felt akin to escaping the prison walls. “When I read, I am in contact with the whole universe. The walls and bars disappear.”

Mildred’s experience is echoed in the Critical Survey, ‘Reading for Life’: Prison Reading Groups in Practice and Theory, research presented evidence of how a rich, varied diet of reading can drastically improve the quality of life for prisoners and address their depression directly. Two things happened when prisoners had access to literature: they reported being happier, even more self-aware. A “significant proportion” even found that some texts helped them access parts of themselves; they rediscovered memories old or forgotten, suppressed or inaccessible modes of thought, feeling, and experience.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Radical Kindness Can Be a Transformative Tool for Change

Moreover, the violence of a carceral state is terribly isolating. As Dadoo explained: “When you isolate someone, you ignore the harm they have lived with completely. it allows the state and society to absolve their responsibility from addressing the social situation that they have created and perpetuated.” The individual remains caged while the system forgets. But prison libraries boldly oppose the violence of confinement; they bring people together, creating clusters of community within a punitive setting. Dr. Rishi Kumar Tiwari who heralded India’s library mission by creating more than 11 prison libraries, called these spaces “cultural community centers.” “They can consider libraries as a place where they can spend their free time productively and ultimately it will help in their rehabilitation,” he added.

In her letters, Kalita remembers old notebooks and indistinct scribbles on the backside of worn copies. The Gita Press dominates most shelves, but the works of Amrita Pritam, Premchand, Gabriel García Márquez, Isabelle Allende fight for space. “There are prayers, notes for loved ones, attempts at learning to write, traces of lives lived between these walls,” she says.

Literature invokes powerful feelings. The renewed empathy softens the internal conflict of guilt and helplessness people may face. “For prisoners who have often struggled with notions of the impact their actions have on others, this is a critical part of their rehabilitation,” as some have noted.

Crime, poverty, and marginalization are socially constructed, and yet we limit the conversation to the individual when we speak of punishment. Kinder interventions like reading can reframe the narrative of looking at an imprisoned individual with stigma and almost as an “evil” being, notes Baljeet.

It’s important to note that these programs can very easily morph into insincerity, as they still exist within the existing carceral system. “Process of self-care and healing is a very personal experience,” Kaur notes, urging caution against any “one-for-all” framework. These interventions can never exist as concessions in the absence of proper living conditions, stringent bail requirements, and a better judicial process.

In Crime and Punishment, which speaks of the friction between the individual and the society,Dostoevsky pointedly notes:“[People] believe that a social system that has come out of some mathematical brain is going to organize all humanity at once and make it just and sinless in an instant, quicker than any living process! … The living soul demands life; the soul won’t obey the rules of mechanics.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

SC Criticizes Madhya Pradesh’s Policy of Rewarding Prosecutors for Securing Death Penalties