Scientists Get First Look at How Bacteria Shapeshift to Resist Antibiotics

The change in form allows bacteria to become invisible to the immune system — and resistant to antibiotics.

In a breakthrough insight into how bacteria become resistant to antibiotics, scientists have proven bacteria change shape to avoid detection by the human immune system and destruction from antibiotic drugs.

Most prior research into how bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics has focused on genetic changes that allow the bacteria to expel the drugs or break them down. The results of the new study have been published in the journal Nature Communications.

“Our study highlights yet another way that bacteria adapt that we’ll need to take into account in our continuing battle with infectious disease,” study author Katarzyna Mickiewicz, PhD, a research fellow and cell biologist at Newcastle University, wrote for The Conversation.

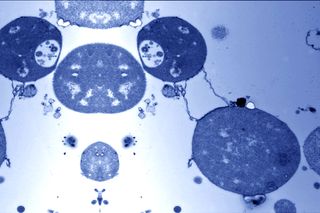

Scientists have known since 1935, it’s possible for bacteria, in certain environments, to shed their protective coating — or, cell wall — taking on a state known as an “L-form” that requires no change to the bacterial genome. It’s a fragile state, but it allows the bacteria essentially to masquerade as human cells, which lack a cell wall. Many antibiotics have been engineered to attack cell walls, as the presence of a cell wall is a clear sign the cell is non-human. In theory, if the transformation from normal bacteria to L-form occurs within the human body, these antibiotics would be unable to find their targets. Natural immune molecules that work in the same way would be ineffective at fighting the bacteria, too. Mickiewicz and the team’s research is the first to confirm that this shapeshifting does actually occur in the body and in response to antibiotics.

Related on The Swaddle:

When to Take Antibiotics — and When Not to

L-forms are difficult to detect in the human body. To do it, Mickiewicz and team cultured urine samples from elderly people with a history of repeated urinary tract infections. They then used fluorescent probes that can recognize bacterial DNA to prove that many different types of bacteria — including some common strains like E. coli and Enterococcus — survive as L-forms in the body. In a second experiment, the team also proved this method of antibiotic-resistant evolution by observing the process of bacteria becoming L-forms in response to antibiotics in zebrafish embryos.

“Importantly, our study shows that antibiotics need to be tested in conditions more reflective of the human body,” Mickiewicz writes, before calling for more research. “It will also be important to investigate what role L-forms may play in other recurrent infections, such as sepsis or pulmonary infections.”

Any future research could have direct implications for India, where a weak public health care system, high prevalence of disease, and weak regulation of affordable antibiotic sales combine to create what Ramanan Laxminarayan, an epidemiologist and director of the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP) in Washington DC, described to LiveMint in January 2019 as “a perfect storm” of antibiotic resistance. Even more alarming is the development of resistance to third-generation antibiotics and drugs of last resort — the medications used when other antibiotics prove ineffective.

“Diseases like pneumonia and typhoid have become difficult to treat. In 70% of the cases, treatment begins with more expensive, third-generation drugs, which are administered for a longer duration than before,” Sunil Gupta, additional director of the Delhi-based National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), told Srishti Choudhary for LiveMint.

India has considered and/or implemented various policies aimed at curbing antibiotic use. One such initiative is the Red Line campaign, which requires antibiotic medication to carry an identifying red mark on the label in order to discourage easy, unnecessary over-the-counter sale and use. While these are important steps in reigning in antibiotics abuse and further development of antibiotic resistance, it’s Mickiewicz and team’s research that holds the potential to save us from the superbugs already among us.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

The Biology of Panic Is Much More Than an Adrenaline Rush