How I Have Sex: ‘Sex is Not Salvation, Marriage is Not Heaven, and Singleness is Not Hell’

This month in ‘How I Have Sex,’ a 42-year-old pastor shares his story on abstinence and how it shaped his outlook of sexual desire.

In How I Have Sex, we bring you candid retellings of people’s sexual lives that explore the multidimensional nature of this human experience. In this installment, a 42-year-old pastor shares his story on abstinence and how it shaped his outlook of sexual desire.

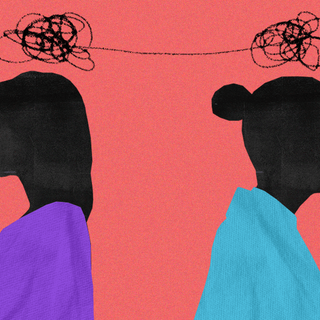

My introduction to sexuality was not from loving parents but in the context of dysfunction, shame, and confusion with an early introduction to pornography. I was laughed at by friends and relatives for not knowing about “the birds and the bees.” That introduction put me on a path to view sexual desire as shameful.

When puberty hit, the shame intensified and I felt a deep sense of self-condemnation in my teenage years. At the same time, my friends and I had a free-flowing and open conversation about our sexual desires and imagination. But with the wider world and my family, there was no healthy, instructive, helpful conversation; shame dominated my soul.

I grew up in a time when sexual expression was widely being seen as a means of validation among friends in school and college. So my desire to have sex with someone I was married to meant I was invalidated as a man among men. There was so much talk—among friends and in mainstream media—about becoming a man that followed having sex; with no possibility for a person to be a “real man” if he had never had sex.

The sexual imagination of Bollywood and Hollywood had a deep impact on my own imagination. When a hungry man sees a feast, it’s difficult not to salivate. I relied on these industries to feed and fuel my imagination. I was absorbed by popular culture and there were little or no portrayals in popular culture of a wise, popular, respected virgin. Every virgin story I ever saw was a loser who was only fulfilled after having sex. I think the most frighteningly close experience I’ve seen of my life was in the film The 40-year-old Virgin. I was 25 at the time and genuinely feared if there was a sequel, it would be my story of “The 30-year old virgin.” At the same time, it fell short a little bit because even that film was ultimately resolved with him losing his virginity, ironically reaffirming the narrative that masculinity is achieved by sexual conquest. Still, it’s one story I can relate to more than anything.

But at the same time, I didn’t like my dependence on [these industries]. I remember Jessica Alba roundly declaring in a press conference: “Everyone in Hollywood always wants you to take your clothes off and I’m just not going to do that.” It gave me a sense that these industries appeared to be liberating but might be more exploitative than they appeared. Yet, what I knew wasn’t enough to overcome my desire.

That narrative gets under your skin and it makes you wonder if you really are the loser everyone thinks you are. What was the point of being a virgin? My identity was beginning to form around my sexuality. If I could go back in time, I would tell myself sex is not salvation, marriage is not heaven, singleness is not hell.

In my teenage years, I was deeply dependent on pornography for validation, comfort, and solace. I used it to satisfy unmet emotional needs, ease the burden of family dysfunction, and satiate the feelings of social isolation. I often speak openly about the effects of pornography on my life. I discourage people from depending on it — without condemning people who are drawn to it because I’ve been there. But it’s hard for me to see it as anything less than exploitative. I find from my experience and otherwise, whatever may be regarded as its benefits, I think they are outnumbered by its costs.

If I could go back in time and speak to myself I would tell myself to see myself as more than just a virgin. While I was single, I sometimes felt like I was getting the raw end of the deal. Everyone is doing what they want to do, why am I denying my body what it wants? I sometimes felt a sense of futility in the waiting.

Related on The Swaddle:

Cultural Trauma Affects PCOS Patients’ Sex Drive More Than The Condition Itself

Sometimes it felt like I lived in a time when people could easily understand two people who didn’t love or know each other having sex. But they couldn’t understand two people who loved each other but didn’t have sex; or even a person who wanted sex but only wanted it with one person, someone he hadn’t even met yet.

I think I can honestly say that I don’t regret waiting until marriage. Most of the time I’m thankful I waited. But there have been many times when I’ve wondered how my life and relationships would be different if I had sex with someone before marriage, even if that person was my wife. When I’m feeling insecure about myself I wonder if I would have been “more of a man” if I had sex earlier.

Like I mentioned earlier, sexual expression was widely seen as a means of validation. I knew friends who spoke of women as conquests, bragged about their exploits, and called me everything from “father” to “pope” to “Jesus ke bhakti.”

I remember one particular time when I was in a car with a few friends, one of whom was a close friend and the others I didn’t know too well. My friend introduced me to the others as a Christian and a virgin. He even made a mocking joke about God having sex with Mary so that Jesus was born. He’s a close friend of mine but I felt exposed and betrayed. I felt like a loser and ashamed that treasured convictions of mine were being treated like trash. I froze and couldn’t say anything in reply. I just sat there and laughed uncomfortably, waiting for the moment to pass.

However I also had close friends—both male and female—who shared the same convictions. We were family to each other and found strength in our friendships that were honest, open, safe and encouraging.

The wait to engage in sex was difficult and transformative. The wait was difficult because it felt like walking towards the unknown. I wasn’t even sure if I would ever get married. Inwardly, the uncertainty of the future was difficult to bear. Seeing your friends all get married was difficult. India itself felt like it was going through a moral puberty. The internet, cable TV, smartphones all brought with them access to sexual stimulation that made any diet nearly impossible. I found myself turning to pornography to gratify my sexual desire.

With it came feelings of shame and inadequacy. Its effects on my mind, view of women and expectations from marriage were not healthy. In some sense, the wait felt like a battle I overcame but in which I might have lost a limb.

It was transformative because I now see I was living on a sexual diet in a time when the pressure I felt—inwardly and outwardly—was to indulge in sexual gluttony. I often wondered if I’m repressing my desires and under somebody’s thought-control. But I’ve realized a diet is the best way to make sense of it now. A diet can be good for your body; it’s not repressing hunger, it’s restraining your appetite. Like any diet, it feels impossible to keep going without close friends, trusted relationships and tight community. This I had in spades and I’m forever grateful.

Also since we are leaders in a church community, when asked about [sex or desire] we want to speak honestly and hopefully about human sexuality. The Bible speaks quite candidly about sexuality. So we feel it strange we Christians can be quite squeamish about it. Also, given the shame and stigma around it, we feel it’s a culture-creating opportunity to speak about sexuality without feeling ashamed about it as if it were something dirty.

My wife and I have a shared view of sexuality as something mysterious and powerful, something sacred, precious and intimate; like the chocolates your parents brought back from trips abroad that you kept in the back of the fridge and only shared with people you really loved and trusted.

It’s hard to describe the feeling after the first time I had sex. It was a long wait and it felt like it was worth it. I think I felt grateful and joyful. My wife is an incredible woman of depth and substance and I couldn’t believe I was married to her. I’m not proud of it, but I even felt a little vindicated. I suppose it was in reaction to jarring memories of being taunted and mocked over a long period of time.

Related on The Swaddle:

Sex Education Is Most Effective When It Focuses on Pleasure, Finds Study

One of the most important things I’ve learned in marriage is sex and intimacy are not the same things. Intimacy is greater and deeper than sex. I can live without sex. I can’t live without intimacy. My wife and I have been married for 11 years and we are still growing in our personal and physical intimacy.

I thought marriage would save me; it actually only exposed me and introduced me to myself. The marriage didn’t come easy to either of us. We both have pasts of pain, trauma, and heartache. Those unhealed wounds reopened in our marriage.

Naively, I thought once I got married I would never be drawn to pornography or self-pleasure again. It was something I wanted to put in the past. But when our marriage got difficult, it was easier to retreat into the familiar patterns of my teenage years and repeat the pattern of treating emotional wounds with physical pleasure. I felt distant from my wife, contempt for myself, alienated from people. The early years of marriage were an awfully dark time.

In my experience, I found self-pleasure was like junk food that killed my appetite for real intimacy. Self-pleasure required no vulnerability. It was a low-risk, low-reward relationship with my body. But intimacy demanded deep vulnerability. It was a high-risk, high reward relationship with another human being whose story was as complex, layered, multi-dimensional, mysterious, and powerful as mine.

To clarify, it wasn’t sex that exposed me, it was marriage. I was seeing myself through someone else’s eyes, as in a mirror, and it was difficult to accept I wasn’t the “good boy” I always thought myself to be. Our intimacy in marriage was tested by my own shortcomings as a husband and a man. I was an only child and had to learn to make room in my life and in my heart for another person. It was my emotional immaturity and self-centredness that were exposed in marriage.

It was through taking a hard look at myself, opening our marriage to mentors and a counselor, doing the hard work of recognizing the effects of a dysfunctional family and unraveling a history of trauma that my wife and I began to come out of the past, meet each other at the moment as if for the first time and begin to write a new future without anything to hold us back anymore. This is an ongoing experience even as I speak. Heart work is hard work but it’s good work.

I’ve realized my waiting for sex was not about marriage or my wife or anyone else. It was about taking ownership of my body and consciously offering it to the one who made me.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Related

Being in On‑Again Off‑Again Relationships Can Impact People’s Long‑Term Mental Health