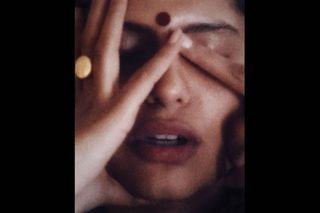

How Indian Photographers Are Subverting the ‘Male Gaze’ in Their Art

Artists are increasingly portraying the “female gaze” instead — but even that doesn’t go far enough.

Victor Hugo wrote, “Curiosity is gluttony. To see is to devour,” and nowhere has this been truer than across cinema, art, and photography — crafts that have historically been dominated by the male perspective. With their evolution, the human eye has sub-consciously been trained to perceive the image of a woman with a “male gaze.” It’s a perception that perpetuates sexual and societal stereotypes of women by setting the subject of the image in the role of an object, something or somebody we regard from a distance — observing and judging, instead of empathizing or feeling. And while female artists are increasingly turning the “female gaze” on male subjects in response, that act of subversion only goes so far.

The term male gaze was first coined by British film theorist, Laura Mulvey in 1975 in her now infamous essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she describes the unquestioned assumption in Hollywood cinema (and consequently, Bollywood) that the perspective of both the filmmaker and the audience is male. More than 40 years later, in most cases, the person behind the camera remains a man, and while his intent may not be to sexualize, in effect, the interpretation remains sexual.

A classic example of the male gaze, in this case, would be the (in)famous Axe advertisements wherein the very idea of a man wearing perfume is enough to attract skinny, big-breasted women who charge toward the male protagonist, fighting with one another for his attention. Let’s take a more subtle but equally powerful example of introducing a female character in a film by panning her body with the camera – e.g., the first shot of actress Megan Fox, decked in tiny shorts, in Transformers.

More subtle examples include the depiction of women in perfume ads of brands like Chanel, Givenchy, Versace. These images douse women in shadows, highlighting a naked thigh or a deep cleavage as they stare right into the viewers’ eyes — inviting them into her world, while characterizing that world as only and entirely sexual, adding to a very one-dimensional understanding feminity. While eroticism can be powerful, it also can be damaging to the overall understanding of women. From women in bikinis selling hamburgers to the enhanced assets of pornographic models, the male gaze supports an unrealistic idea of feminine characteristics.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Toxic Culture of Sci‑Fi and Its Fanboys

By contrast, the female gaze is as revolutionary as it is nascent and scattered in meaning and interpretation. Often used as a way to describe art created by women, a more fitting definition would be art with a feminist bent. The term has gained mainstream currency with the rise of artists as diverse as the rapper Cardi B, in her Grammy-winning albums and music videos, both gauche and rebellious with her very history as an ex-stripper, and TV showrunner Jill Soloway, who is known for challenging the male gaze in their award-winning show about a family navigating the father’s transition to a trans woman, Transparent. Soloway, in fact, divides the female gaze into three categories: the act of feeling versus looking; using the body as a receiver of the gaze, e.g., how the camera shows the audience what it feels like to be ‘seen;’ and returning the gaze, e.g. ‘I see you seeing me,’ wherein the object is the subject, effectively reversing the objectification.

When the lens is reversed onto a male subject, to explore the idea of male objectification, the results are radical. Case in point is Shreya Dube’s powerful, intimate black-and-white portraits of her partner, which use light, perspective, and shape to draw attention to their meaning. While the reversal of gaze, at first glance, perpetuates the continued objectification of the subject, on a closer look: the subject becomes more one who belongs to love and desire, rather than one subjugated to and by it.

“When I was younger, I made an effort not to shoot women the way some men do. I made an effort to photograph my girlfriends not the way I was used to seeing my favorite actresses represented on posters. After a while, you find your own point of departure and it becomes less about not shooting like others and more about how you see the woman in front of your lens. … For years, I was the subject to a photographer who shot a lot of nudes — no doubt that I learned a lot while being photographed, at times even objectified,” Dube says. “I imagine progress will be made when both men and women can move freely between the position of subject and object. Nowadays, many of us are in tune with the masculine and feminine parts of our own personality, so the question I’m asking myself these days is that: can the female gaze be that simply explained? Maybe the way I see, it can not be entirely explained through the concept of my designated gender; it is also the culmination of my life experiences as much [as] my need to want to represent woman not through the eyes of men.”

Dube hits on a dilemma at the heart of the “female gaze”: While the act of objectifying a man through the eyes of a woman remains revolutionary, it ultimately lends itself to a very “male” idea of what the female gaze should be. Both the male gaze and the female gaze can reduce a subject to an “object” or aid the “zoo-effect,” as Beth Lazroe, an American photojournalist and professor, terms it, wherein the person or the situation is ‘otherized.’ Inverting the lens to sexualize men might help break a gender-constricted norm but ultimately, in doing so, it reinforces the binary of the male gaze and confirms and sustains an existing stereotype.

Related on The Swaddle:

When The Photographer Is Always Mom

This is why other Indian artists are beginning to explore the intersectionality of the “female gaze” in the depiction of other women. Karen Dias, an independent documentary photojournalist whose work focuses on women, indigenous communities and the environment, holds that the female gaze, in its iteration as a reaction to the male gaze, is incomplete, since it does not include the gaze of other genders, sexualities and, especially in India, castes, and communities.

“I’m not going out consciously trying to subvert the male gaze — that would be too contrived. Because of my personal experiences as a woman, my views, ideas and work are automatically compartmentalized as the ‘female gaze’. My work does, for a large part, focus on women and those are the stories I tell, not just because of my gender, but also because of what I see and feel, what makes me angry, what I read and what I want to investigate. In a small way, anything that women do that is progressive, inclusive and supportive, automatically subverts the male gaze,” she says.

A gaze belonging to any one gender creates a power imbalance — something conscious human beings, feminists or not, struggle to overcome every day in life. Historically, images have the power to shape and influence what can be termed as the “truth;” as long as our participation in what is depicted remains limited, so will our understanding of what we know to be true. As we collectively move towards a more gender-equal society, the real debate at hand is not ‘male gaze’ versus ‘female gaze,’ but rather, whether we can find a gaze that accurately presents and represents without manipulating reality to serve one’s agenda or propaganda.

Alina Gufran is a screenwriter, filmmaker and features writer based out of Mumbai. Third-culture kid.

Related

This Is My Family: the Widower Who Is Dating Again at 63