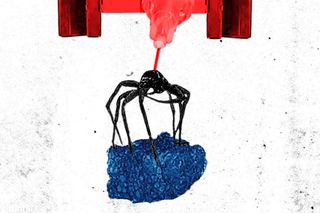

How ‘Necrobotics,’ or Using Dead Creatures as Robots, Is Changing Science

It started with scientists using dead spiders as mechanical claws. But necrobotics raises ethical questions about how humane treatment of animals extends beyond their lifespans — into death itself.

A team of engineers from Rice University recently reanimated dead spiders. They didn’t bring them back to life — but they were able to use the spiders’ corpses as mechanical claws that could lift objects many times their own weight. This is ‘necrobotics’ — an emerging field of science that uses dead creatures to perform mechanical tasks (for now).

The use of spiders isn’t incidental. Spiders move using hydraulic pressure rather than muscles — and a body part called the prosoma chamber facilitates movement by pumping bodily fluid into the legs. By inserting a needle into the prosoma chamber of a dead spider, scientists were able to replicate the furling and unfurling motion of spiders’ legs — thereby creating a gripper. The necrobotic spiders could then pick up delicate electronic objects, and even other spiders of the same weight.

Further, these spiders were able to lift things nearly a 1,000 times before wear and tear affected their ability to do so — a problem of dehydration that is surmountable.

“The concept of necrobotics proposed in this work takes advantage of unique designs created by nature that can be complicated or even impossible to replicate artificially,” the researchers wrote in their paper, published in Advanced Science. The paper introduced the concept of necrobotics to the world — and in the process, raised several questions about the future of the field itself.

There are several advantages to it. It makes an important robotic component completely biodegradable — plus, it also bypasses the engineering requirement to replicate complex animal movements.

Integrating biology with robotics is not new. We’ve already developed DNA-based nanorobots to study minute biological processes. Biomimetic robotics is, in a sense, a predecessor to necrobotics — in that it’s tried to create robots that can mimic the astonishing feats of animals in real life. Take, for instance, the development of fast “soft robots” that try to imitate a cheetah’s movements, or bio-inspired robots based on electric fish.

Then, there are biohybrid robots that integrate biological material into robots whose movements are improved by the added biological functionality. “The developed biohybrid robot composed of skeletal muscle tissue and collagen structure can be employed within platforms used to replicate various motions of land animals,” noted one study on the same.

Related on The Swaddle:

Some have raised ethical objections to the field, though — alleging that it’s as close to necromancy as we’ve ever got, and fiction has already warned us about the moral compromises it involves. “There’s a lot to be learned from biology and nature,” said Rashid Bashir, a bioengineer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who wasn’t involved in the study. But there’s still one pertinent question to ask, Bashir adds: “how far do you go?” What does it mean to reanimate a corpse to do one’s bidding? It could be an environmentally sustainable way to innovate — but it could also snowball into morally grey areas where we don’t just stop at spiders.

Previously, researchers drew upon “biomimetic ethics” as a way to question “how we produce, use, and consume things, and, as such, may potentially provide the basic ethical framework required to underpin the transition to a circular, bio-based, solar economy.” In other words, thinking about ways to use what’s already in nature without extracting more from it could be an ethical framework that underpins advances in robotics.

On the one hand, necrobotics could be no different from what we’ve been doing for thousands of years already — repurposing dead animal parts for clothing, tools, and of course, food. “Bioinspiration and biohybridization have led to new, exciting research, but humans have relied on biotic materials — non-living materials derived from living organisms — since their early ancestors wore animal hides as clothing and used bones for tools,” the researchers write.

On the other hand, it could pave way for something less humane. “The fact that the spiders are dead in the current experiment may actually be a form of kindness. From a pure research/engineering perspective, the solution to the dehydration problem might be to keep the spider alive while taking over the hydraulic portion of its body. Then, why stop at spiders? Would installing a nervous system shunt in mammals be the next step?” wrote Florian Pestoni, a robotics practitioner.

But if biomimetics was the predecessor to necrobotics, science may have already gone a step further. Back in 2015, researchers tapped into a cockroach’s central nervous system while it was still alive — essentially creating remote-controlled cockroaches. This, too, is based on the underlying principle of using something in nature that’s difficult to replicate.

More recently, there was an arguably more humane upgrade to this: the same team of researchers created tiny solar backpacks for roaches to wear and be remotely controlled by. Cockroaches are some of the most disaster-resilient creatures we have — and the development of these cyborg-cockroaches is precisely to aid in disaster relief measures. “The batteries inside small robots run out quickly, so the time for exploration becomes shorter… A key benefit (of a cyborg insect) is that when it comes to an insect’s movements, the insect is causing itself to move, so the electricity required is nowhere near as much,” said Kenjiro Fukuda, who led the research.

What makes necrobotics — and all its related fields — compelling, are the questions it raises about scientific values. We’ve graduated from using nature’s blueprints to stealing the equipment itself, so to speak. The applications may be beneficial or even just benign. But it points to a need for more conversations about ethics in science — and balancing questions of utility against unjust power.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Cannabis Use May Make People Overestimate Their Creativity, Study Finds