How Patriarchy Drives Mental Illness, Superstition to End Lives in ‘House of Secrets’

All it took to end three generations of the Bhatias–a family like any other–was a patriarch’s undiagnosed mental illness.

In Netflix’s latest documentary ‘House of Secrets: The Burari Deaths,’ we eventually learn that what plagued the ill-fated Bhatia family was not such a secret after all. A fatal mix of undiagnosed mental illness and the patriarchal norms of the average Indian joint family set off a chain of events that led to the bone-chilling discovery of ten bodies hanging “like the roots of a banyan tree” in a Delhi suburb one morning in 2018.

The documentary, directed by Leena Yadav, explores the mysterious deaths of 11 members of the Bhatia family, who lived in Burari, New Delhi. Throughout three episodes, we follow the disturbing tale of the wiping out of three generations of a family in a single night, seemingly without rhyme or reason. There were no signs of struggle, but how eleven family members — at various stages of life and with much to do yet — died by mass suicide baffles the imagination. As one journalist put it — it was difficult to characterize it as either murder or suicide. It was simultaneously both and neither.

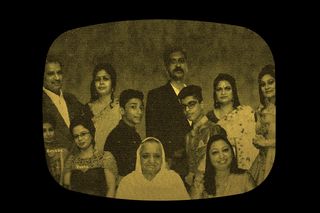

By all accounts and appearances, the Bhatia family was a perfectly “normal” Indian middle-class joint family. Images of the family in happier times, juxtaposed with their unexpected mass death, send shivers down the spine. But the particularly hair-raising details emerge with the revelation of diaries detailing the “Banyan tree ritual” in an instructional manner as if a “third entity” was controlling the entire family.

When it feels surreal, when viewers watch with detached awe and horror, the series draws us back into how similar rather than different the Bhatia family was to most others. The genuinely disquieting part of it all is the realization that what happened to them could just as quickly have occurred to any other family. The ingredients for the recipe already exist in most families: unquestioning obedience to a patriarch, denial over mental illness, secrecy, shame, and excessive control over each family member.

The documentary draws attention to the stigma around mental illness, but it’s clear that there is an underlying gendered element at play. Lalit Bhatia, one of the middle generation men, allegedly had an undiagnosed mental illness after experiencing trauma. According to psychiatrists who analyzed the case in the documentary, this eventually led to him “hearing” his dead father’s voice. The patriarch’s death left a void of authority in the family, leading to Lalit Bhatia filling it ostensibly by being the medium for his father’s voice and command.

Related on The Swaddle:

It is difficult to ignore how mental illness in men, coupled with faith and superstition, distorts traditional patriarchal family dynamics into a grotesque doppelganger of sorts, taking these patriarchal forms of control to their logical and extreme conclusions. Lalit supposedly experienced prolonged psychosis that transformed the family into a small cult. As one expert put it, the allure and power of the authority figure in cults are in their transgression of mortal expectations. But the missing piece of the puzzle, it would seem, is that it was a man in a position of power within the family who was able to actualize his control through his mental illness, galvanizing superstition to legitimize the illness in turn.

I wonder whether the same outcome would have come to be if it had been a woman experiencing the same thing. Judging by several accounts, it is likely that a woman would have been subject to violence for similar delusions. Narratives of “possession” by spirits have led to different outcomes depending on who the “possessed” person in question is. A key difference is that while some can self-proclaim their possession for greater legitimacy, as was the case with Lalit, families or communities can declare someone as possessed to justify brutal violence against them.

This is what makes the documentary timely. It comes in the backdrop of renewed conversations about how superstition tears communities apart and how their power is in their implicit invoking of fears around changing norms. Take the example of a family from Ratlam, Madhya Pradesh. A recent Caravan investigation explored how a family brutally killed three of its own in response to what boiled down to insecurity over a woman’s financial independence. The family claimed that an entity possessed the woman, culminating in a tragic series of events that led to her husband’s and child’s deaths.

Or take the educated family from Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, who killed their daughters believing that evil spirits possessed them. They thought that their daughters would come back to life freed of the spirits if they were killed.

Often, like with the Burari family, superstition may not have the effect it does if underlying patriarchal anxieties did not drive it. But as experts observe, the triggering event for the final act, after years of control by the apparent patriarch’s spirit, was a young woman’s engagement. Fearing the loss of control, Lalit Bhatia allegedly withdrew inward and seemed out of sorts; ten days later, all eleven family members were dead.

Leena Yadav’s lens shows a nuanced portrait of how class anxieties, patriarchal norms, and a denial of the reality of mental illness all converge into devastating consequences. The series prompts a larger conversation about mental health in India and how so often its association with the uncanny and superstition can be deadly depending on the actors involved. All in all, the case shows that mental illness goes beyond an individual. If they are powerful enough — they can pull several others into an orbit that spirals into devastation and decay if left unchecked.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

A History of the Handbag From a Practical Necessity to Creative Canvas