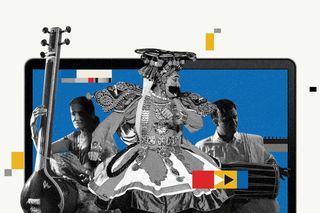

How Performing Arts Like Theater, Folk Dance Survived the Pandemic

“Artists who were financially more secure…actually found this a good time to practice, think, ruminate, conceptualize and learn something new. But the artists who couldn’t afford a break…have been devastated.”

A colorful bright ghagra, carefully embroidered. Strings of silver jewelry. Aasha Sapra was five years old when she saw Kalbeliya dancers, women in her family, donning this get-up. Aasha also began learning the Rajasthani ethnic art form at that age; she must have been 12 when her bare feet became familiar with the stage.

This union was interrupted some 18 months ago. For Kalbeliya dancers like Aasha, and other performing artists who relied on a live community, the pandemic changed art and livelihood. India’s sudden lockdown, the internet’s limited ambit, and the lack of government support left millions struggling, particularly local artists who derive meaning and income from physical spaces and real-life connectivity.

“Ehsaas toh bahut hota hain,” she says. “We definitely feel the loss [of the stage.]” The stage — and this may be any sphere that elevates the craft — is surrounded by an audience, nurturing energy that drives the artists. Abrupt closure threw art, artists, and their livelihood into freefall; performing artists struggled — economically, personally, and creatively.

***

It is hard to quantify a loss of a feeling. M.D. Pallavi, a 42-year-old singer, struggles to put into words, or even make sense of, what the pandemic did to her vocation. The moment when India announced the first lockdown on March 25th stands out in everyone’s memory. “The lockdown, especially the suddenness of it, was extremely difficult for a lot of local artists,” Pallavi notes.

“Performances were canceled, there was no compensation, no future in sight.”

Bhavesh Shah, the founder of Mumbai Theater Festival, speaks of a similar struggle: “Theatre is all about live experiences, pandemic posed a big challenge to the theatre industry as no performances were allowed and even today across the country auditoriums are closed.”

As an unorganized sector, the trade of performing artists depend on a lot of variables. The rushed lockdown, thus, jeopardized stability for artists, leaving them emotionally and financially helpless.

In Jhola, a small village in Jodhpur, another Kalbeliya dancer Suwa Devi supported her entire village, of almost 51 families, before the pandemic. Many members of the Kalbeliya community similarly provide not only for themselves and for their family but also for the larger community; sometimes, their entire village.

The pandemic, and no government support, stripped them their already sparse income and visibility and led to further isolation. Many local artists resorted to odd jobs, shifted back to their hometowns, or started other small businesses.

Related on The Swaddle:

One Year Later, Are We at Risk of Forgetting the Lessons We Learned During the Pandemic?

In the absence of physical, community spaces, some artists ventured on their own to attract a digital audience and partnered with NGOs to boost their reach. Some, like the Tamil Nadu heritage theater group who perform Kattaikkuttu, resorted to crowdsourcing.

Taking the craft to cyberspace also meant making peace with the digital stage. Zoom and Instagram livesbecame new platforms for some artists to collaborate, experiment, conduct workshops. New ways of engagement, more flexible processes, opening up a world of the online; expanding our reach of audiences and connecting us across the globe in the digital have all emerged.

The internet’s relationship with performing arts has always been tumultuous; the circuit of codes and broadbands is hardly a suitable replacement for performances shaped by the palpable energy of live audiences. Irrespective of how big the world wide web is, the devastation triggered by a disconnect between the artist and the audience is acutely felt.

But the role of the internet is not binary — the transition helped some by taking their craft online; it put others at a disadvantage. A large section of performing artists does not have the resources to take their art online or is not connected to the internet. Or, their audience base has no access to the net. The pandemic laid bare inequities in terms of technology and resources.

“Privacy inside your house to do your office/professional work is a privilege in itself. For artists to be able to create work out of their homes in these times has meant that they need to have the physical and mental space to do it. I have been lucky enough to be able to work online,” Pallavi says. Notably, artists are not only struggling to make ends meet, but also do not have the provision to access their studios and art spaces during this crisis.

As with the rest of the country, the severity of the pandemic’s impact was not the same for all artists — it was never a leveler. “Artists who were financially more secure, who had some savings and family support to fall back on actually found this a good time to practice, think, ruminate, conceptualize and learn something new. But the artists who couldn’t afford a break, who depended on their everyday earnings to see them through, who have no family support, have been devastated,” Pallavi noted.

“Few of the senior actors moved on to the OTT platforms, however the junior artists, the backstage staff all faced financial crunches,” notes Bhavesh Shah.

The gap also raises the question of the impact on women artists. Notably, women are more likely to be disconnected from the world wide web. A 2021 study by UNESCO noted women’s participation in art and music reduced more than their male counterparts due to the digital divide during the lockdown.

“The digital divide remains a pressing concern, with women disproportionately facing obstacles to access digital tools for artistic creation and distribution including digital music platforms, online tutorials, and sound-mixing software,” the report notes, adding that “worldwide, 250 million fewer women than men use the Internet.”

And while Pallavi embraces this new culture, she strongly believes that “until it can be easily available to a larger part of the population, it will remain a niche and elite choice.”

Menaka Rodriguez, head of outreach at the Indian Foundation for the Arts, notes that, in a country where systemic support for the arts and culture sector is absent, there are limitations on how artists can consistently create work online.

Thus, the idea of a hybrid future, which visualizes a marriage of the physical and digital space, risks exclusion of many. “…because of the limited access to a community/audience/gathering, it cannot be said enough that these options are still limited to a small section of performers who have access to resources… some art forms cannot be replaced completely by the online.”

***

Related on The Swaddle:

Women’s Representation in Art, Music Reduced Under Lockdown Due to Digital Divide: UNESCO

Although many artists have found ways to continue practicing and sharing their art, “[i]t is not enough to celebrate this resilience,” Rodriguez says. What irks her is the presumption that the onus is always on artists to find solutions and they always find ways to do so.

“We need to demand more of our government; we need a government that can offer a universal basic income to all artists, supports infrastructure and communities, and makes provisions of relief funds for artists at the very least.”

The lacking support she refers to reflects the absence of institutional scaffoldings in place. What was unearthed during the pandemic was the story of a shape-shifting obstacle course performing artists have dealt with over the last 16 months.

A report by Sahapedia, an online arts repository, analyzed budgetary figures over the past five years to show how arts and culture in the country needed enhanced funding; the lockdown only accelerated the economic crunch the industry had already been facing.

Pallavi agrees: “Artists are very low on the priority list for the government. In some states, governments have reached out and provided some financial support to artists… but it is too little, too late.” She mentions whatever funding the Karnataka government had for classical arts and local theatres pre-pandemic has dried up. No new projects, festivals, or grants have been offered since the pandemic began. A similar trend plays out across the country.

Moreover, state funding is riddled with eligibility criteria and markers that exclude many. A lot of vocations, such as playing harmonium, are not recognized for government support and are thus excluded from these safety nets.

“If we do not address systemic problems, we are creating an environment where already existing inequities will only get magnified,” says Menaka.

Undeniably, the arts and culture are central to the thriving of any society. Especially in troubled times like a global pandemic, it’s what keeps people going and reminds us of what’s worth saving.

Arguably, the arts moving to an online space brought some positives for the audience. It not only meant more people could access it but also helped keep them sane. “In our isolation, the arts have meant even more to all of us, to keep us grounded and connected to each other. Our interactions, while sometimes unreal, also offer a strange intimacy, in the manner in which we are able to deeply engage with a work,” Rodriguez says.

“It has allowed me to go back, again and again, experiencing works anew.”

Each industry has its own story to tell — but we are at risk of romanticizing the survival of the performing arts, without fully understanding the message they carry in its tones and effortless strokes. The discourse around performing arts, the changes, and challenges, then concerns both; it also undrapes faultlines, truths, profound observations about the industry — and what holds it all together, ambition.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Is This Normal? “I Hate Music”