How ‘Political Gaslighting’ Undermines the Truth

The subversion of reality and twisting of facts on a mass scale make it difficult for citizens to agree on what the truth is.

To “gaslight” someone is to manipulate them into questioning their perception of reality. If this sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because it is — political gaslighting is fast becoming the defining feature of our times.

The process of political gaslighting makes use of certain techniques. “[It] utilizes deceptive and manipulative use of information with the motivation to destabilize and disorient public opinion on political issues,” Farah Latif, a communications expert from George Washington University in the U.S., noted in a paper.

In reality, this translates as creating false, alternate narratives not based in reality; calling them irrational or undermining their sanity for questioning the gaslighter’s narrative; covering up lies to make them sound convincing, and so on. Gaslighting makes use of words and power — two things that feed off inequality. Latif adds that political gaslighting becomes a strategy to “garner support for or against an ideology, viewpoint, or policy.”

The result of this manipulation is pointed. Being gaslit on a mass level undermines the public’s capacity to think about policy in the long and short-term (and their ability to have a say in it), distorts truth and reality, and creates a sense of distrust among the public. The idea of gaslighting is mostly discussed with respect to intimate partner relationships or family dynamics; but in a political sphere, experts note its impact on mass paranoia, confusion, pain, and uncertainty.

Political gaslighting may not always be called by this name. The downplaying the administration’s wrongs, discrediting political opponents, encouraging deliberate misinformation, and diverting attention from relevant news are all markers. Notably, when the government says no one died in the last months due to an oxygen shortage, despite multiple first-hand accounts, the line between fact and fiction becomes too thin.

Typically, gaslighting is a tactic used by powerful individuals with narcissistic tendencies who seek to manipulate another person into their control. What happens when individuals do this to more than one person? What if the grand vision of control is directed towards a whole nation?

According to Latif, there are two distinct victims of political gaslighting: the gaslit (those who are successfully manipulated), and those who hold opposing views (journalists and researchers). Political gaslighters may try to silence the latter.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Govt Celebrating “Power of Positivity” Is An Example of What Toxic Positivity Looks Like

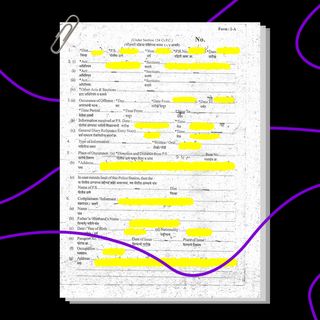

The first, controlled, and carefully planned instances of political gaslighting were seen in Nazi Germany, in which dissidents were toyed with in many ways — including the sending and receiving of fake letters attributed to them. A very similar technique — with a slight modification of letters on laptops — is believed to have implicated Indian activists.

The technique is also used to stoke communal fires and overwrite history; leading to alternative narratives about ourselves as a people.

Further, the pandemic saw an alarming rise in political gaslighting — with leaders worldwide calling Covid19 a “conspiracy,” saying there is no vaccine shortage when there is, among other manipulations downplaying the severity of the situation. These abstract statements naturally have devastating consequences for people who have suffered during a crisis. In India, the government’s claims about the pandemic — pointing at communal bogey to divert attention from the real causes, claiming premature victory over the crisis — have translated into Covid-norm defying behavior. If the pandemic has shown us anything about politics, it is that political gaslighting is not just rhetoric — it can be deadly.

Researchers have also distinguished between overt and covert political gaslighting. The former happens when a speaker explicitly peddles demonstrably false information while presumably being aware of the falsity. Think leaders countering public memory about an event witnessed in real-time (“no one demolished the Babri Masjid”) or misrepresenting reality through denying public experience (“India’s vaccination drive is a success”).

The latter happens when the speaker makes ambiguous statements that cannot be conclusively refuted. Examples of covert political gaslighting include shedding crocodile tears (about purported violence during protests), misrepresenting one’s own beliefs (politicizing the pandemic through the distribution of supplies yet denouncing the same), emotional manipulation, or any instance where the audience cannot access the truth.

A litmus test for identifying political gaslighting, therefore, is that at all times, the audience always has a reasonable basis to doubt the claims made by the gaslighter.

The impact of each such instance is chilling as a whole. If we consider a nation’s electorate as a single unit, the distortion of reality leads to a public cognitive breakdown in terms of what the truth means, what facts are real, which ones are “propaganda,” and who is victimizing whom. The book “Gaslighting America” notes how former U.S. President Donald Trump manipulated American voters into questioning their own histories, doubting established scientific facts, undermining devastating crises, and drawing on sexist, racist stereotypes, among many other classic gaslighting tactics.

Researcher Alex G. Sinha, in an article published in the Buffalo Law Review, identifies political gaslighting not by the gaslighter’s intentions — but by the effect their manipulations have on the public; the effects include triggering doubts about public recollections of “settled matters of historical fact.” These effects are magnified by the power asymmetry that exists between the speaker and the audience — the greater the asymmetry, the more destabilizing the effects.

“When confusion, diversion, distraction, and disinformation are ramped up so they become an omnipresent pollutant of public debate, we may end up losing faith in the very possibility of truthful discussion – or in our own views,” wrote Stephan Lewandowsky, a professor of Cognitive Psychology at the University of Bristol, U.K.

The subversion of reality and twisting of facts on a mass scale make it difficult for citizens to agree on what the truth is. If denying the reality of the scale of death, what caused it, misleading the public about management, and emphasizing a “positive” outlook on an unfathomable tragedy seems like a familiar form of political gaslighting — it’s because it is.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Do People Have a Legal ‘Right To Be Forgotten?’