How Tech Companies Take Away the Right To Repair Our Devices

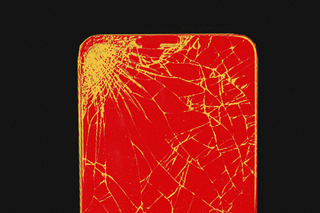

By making electronic devices difficult to fix, tech giants generate tonnes of e-waste by forcing customers to buy more.

With the COP26 coming to a disappointing close, many feel that leaders are dilly-dallying for far too long on environmental policies. In this context, the right to repair movement is a citizen’s movement that can serve as a powerful ally in environmental advocacy.

Essentially, the right to repair pertains to electronic devices, whose technology is kept behind closed doors and inaccessible to third-party repair persons or consumers if anything goes wrong. Brook Stevens, an American industrial designer, coined the phrase “planned obsolescence” to describe how manufacturers shorten the lifespans of their devices, thereby forcing consumers to replace them with new ones faster.

At the heart of the idea is taking back some of the unlimited power that big tech has in dictating how consumers live their lives. By making devices that we increasingly rely on for a functional life, tech companies become indispensable entities of our economy. In turn, their indispensability gives them impunity to use tactics that encourage greater consumerism to generate more profits for themselves. The cost? Individual financial agency, untold environmental damage, irreversible harm to small businesses, and many more.

Take Apple’s notorious ploy to slow down older iPhone models’ software, and not inform consumers. This effectively forces them to “upgrade” to a newer device, even when the older one works perfectly well. France’s competition commission fined the company for doing this, but it is far from the only strategy — Apple also has screws that cannot be opened with a regular screwdriver or common appliance. And many other companies have batteries that, once damaged, cannot be replaced at all.

The insidious thing about it all is that tech companies have the technology and wherewithal to make their products long-lasting. They just don’t want to, because it would mean fewer sales. The website Right To Repair puts it like this: “Manufacturers do not have any rights to control property beyond the sale. Limitations on repair have become a serious problem for all modern equipment that also limits how equipment can be traded on the used market.”

The right to repair movement thus asks that manufacturers make authentic spare parts easily available so that devices last longer and are more easily reparable. Predictably, tech giants like Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, and Tesla have come out in strong opposition to it. They cite intellectual property and security risks to opening up technology this way. In the European Union, the movement made considerable legislative strides, and the idea is gathering steam in the United States too.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Swaddle Spotlights Tech Inclusivity at the World Economic Forum’s India Summit

But the movement has urgent implications for India, which is the world’s third-largest e-waste generator, producing a whopping 3.23 million metric tonnes of waste per year. A recent study noted that computer equipment accounted for 70% of this, followed by phones at 12%. According to the Global E-Waste Monitor Report 2020, India’s e-waste production rose by 2.5 times in six years, as of 2019. E-waste also causes innumerable health hazards and consequences for humans and other biodiversity in the environment.

The World Health Organization reiterated as such earlier this year, when it said that the “tsunami of e-waste” is putting millions of children at risk of developmental disorders, lung and respiratory impairment, damaged DNA, and myriad other complications.

When mapped geographically, the issue also becomes political. The sites of e-waste dumping are disproportionately where the poor and the marginalized live too. Adding to the waste, therefore, has a direct impact on the health and well-being of many people in India.

While government regulations on e-waste management sought to improve things, the looming climate catastrophe requires that we ask questions about the sources of waste.

The right to repair movement, beyond being a consumer rights movement, also has implications for the environment in this way. With governments becoming even laxer in regulating big corporate players, a movement pushing for legislation that gives consumers their agency back is vital.

In India, there is also a social justice argument to be made for the right to repair. Smartphone usage is still a relatively new, but a burgeoning phenomenon, especially during the pandemic. Legislation here should thus include open software to allow families to use a single device for longer periods.

“The central purpose of the guidelines ought to be the promotion of public welfare, which maximizes the impact of technologies on well-being. There are issues of choice and affordability coupled with the exercise of fundamental rights and freedoms including but not limited to work, education and free speech,” write Jai Vipra and Shrinidhi Rao for The Federal.

Ultimately, the right to repair is about fighting back against the “end of ownership,” as Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz put it in their seminal text. When you no longer get to use your device on your terms after purchasing it, the seller still has a say over it, which effectively nullifies ownership. This is increasingly the case with digital goods, and it’s a problem on multiple levels beyond the individual. By allowing tech companies to have so much power, we set ourselves on a path for inevitable destruction even as the companies gobble up profits in a dying world.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Smog in Delhi Leads to Pandemic‑Like Lockdown for a Week